I. ORIGINS

“We’re creatures of habit. If you like something, you stick with it. You don’t just change for the sake of changing.”

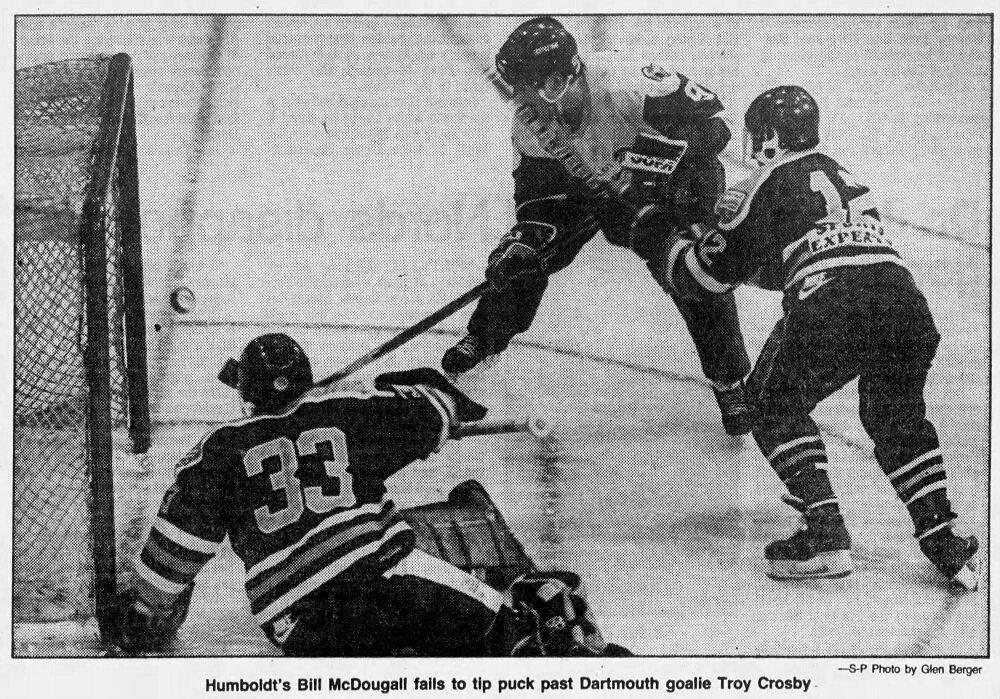

- Troy Crosby [52]

This family never cared much for change.

This held true for heritage and hearth; for decades, the greater Halifax region of Nova Scotia was home. This was where, in the 1940s, Sidney and Nancy Ball reared their three children, Ralph, Gerry, and Linda [122, 254].

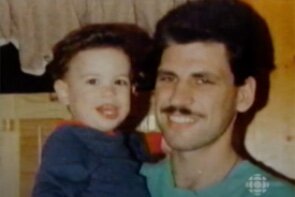

Years later, Linda would hand down her father’s name to her son, Troy Sidney [226, 40:03].

Years after that, it was passed on to another Sidney.

“Cole Harbour, a suburb of Halifax, is typical of any small town across North America. Drive through the neighborhood and you’ll pass simple homes with pristine, green lawns. The Ma-and-Pa businesses still stand next to the Walmarts and Sobeys. Gas stations and Tim Hortons coffee shops litter most corners.

“But Cole Harbour does have its distinguishable traits as well. Bodies of water emerge to encompass swaths of land. Boats and ships line up along the harbor’s docks, rising and falling in submission to the undulating demands of the tide. The smell of the Atlantic Ocean blows along the boardwalk on a chilly afternoon’s day” [67].

Tucked away from the enormous metropolitan centers of Ontario and Quebec, the Maritimes have a particular hold on their people. Sid had it in him, the “small town, small Province, humble upbringing” that meant deep down, Cole Harbour would always be home [67].

The sort of town where “you [made] one phone call home and everybody [would] know within 10 minutes,” Cole Harbour was small enough that Sidney’s midget coach played hockey alongside Troy and went to school with Trina [1, 9:37, 24]. Where Sidney came from, “a good family and the blue-collar Maritimes [...] defined him more than anything else” [The Rookie, p. 55]. For many years after Sidney left the Maritimes, Sidney’s parents still lived in the same split-level house where he grew up, “a few blocks from a shopping plaza where young Sidney would rollerblade if Trina needed him to pick up something for dinner” [52].

Troy and Trina Crosby had both grown up surrounded by hockey. Trina’s large family (7 siblings in total) was especially involved. Her brothers Harry and Robbie Forbes played hockey across Nova Scotia, with 19-year-old Robbie playing alongside a 15-year-old Mario Lemieux on the 1981-82 Laval Voisins [245, Most Valuable, p. 40, The Rookie, p. 286].

“I do have these memories of Mario playing as a 15-year-old and he was pretty magical. Even at that age you knew he was destined to be something spectacular and Sidney brings out those same types of emotions. You just know there’s something special about him. They’re two totally different players, but special in their own unique way.” - Robbie Forbes [367]

Robbie had been a “legendary senior hockey player in Newfoundland,” and played several years in the Netherlands and Britain. He went on to become an executive at Tim Hortons for nearly 20 years before launching his own sports marketing company in 2015 [30]. Sidney’s cousin, Forbes MacPherson, bounced from team to team, playing for eight different teams in six leagues—including 10 games with the Baby Leafs—for nearly a decade, ending with the CHL’s Bossier-Shreveport Mudbugs in 2003. A different Robbie—this one Robbie Sutherland, a cousin—was the captain of the Halifax Mooseheads before playing with his twin brother Brian at Acadia University. Jeff Sutherland, another cousin, played at Dalhousie University [42].

“I played with his uncle, Robbie Forbes, who was one of the smoothest and skilled players ever to play junior and university hockey in the Maritimes. And I coached his dad, Troy, in junior. Troy was probably the most competitive and driven player I ever coached. My first comment was Sidney had all the skill and hockey sense of his Uncle Robbie and all the determination, drive and competitiveness of his dad.” - Darren Cossar, executive director of Hockey Nova Scotia [The Story of…, p. 7]

“The whole family, on both sides, there’s hockey everywhere you look,” said Sidney. As one of the younger kids in the family, he enjoyed worming his way into pick-up games and earning attention from his uncles and cousins. “We used to give him our old skates and stuff like that,” said Sidney’s cousin Robbie. “When they would come over to our house we would fool around playing knee hockey and games like that. It was funny. When we were younger I always thought he was going to be a fighter because he was pretty scrappy when we’d be playing road hockey or something. We used to always joke around with him and get him going. He always used to throw his gloves off and stuff like that” [367].

“I can remember when I used to go over to see Robbie and Brian when they used to work for the Mooseheads. They were water boys and stick boys and I used to try to get anything off them when I was a kid, like [stick] blades or whatever. I managed to get a few things but I still remember trying to get my hands on anything to do with hockey when I went over there. It was always fun. It made for great family times.” - Sidney Crosby [367]

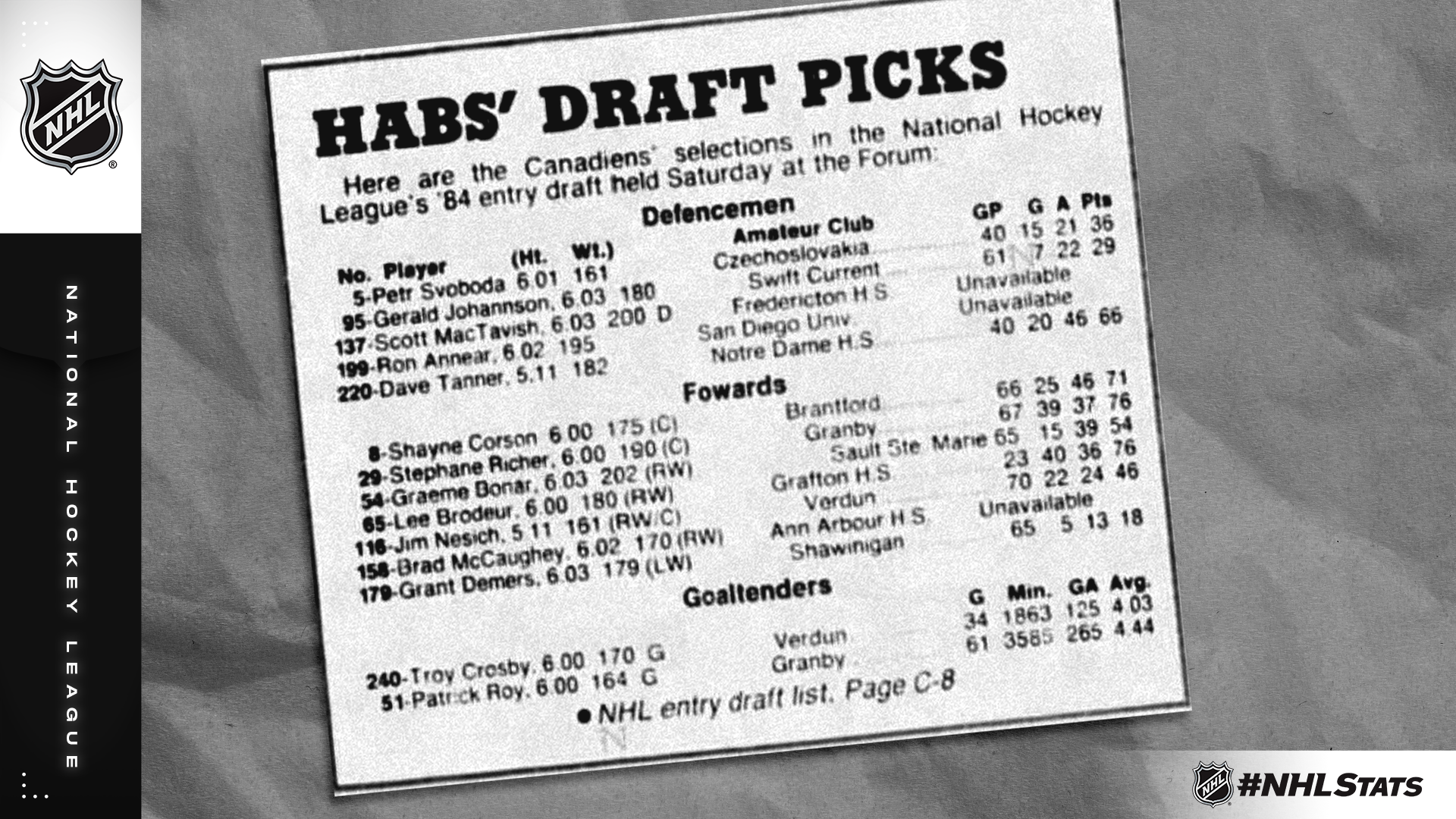

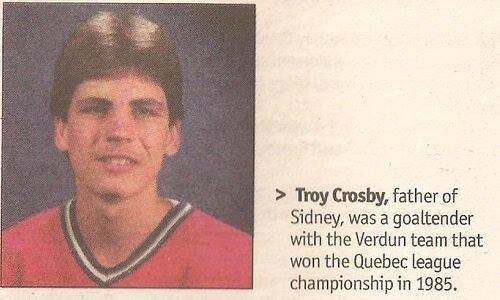

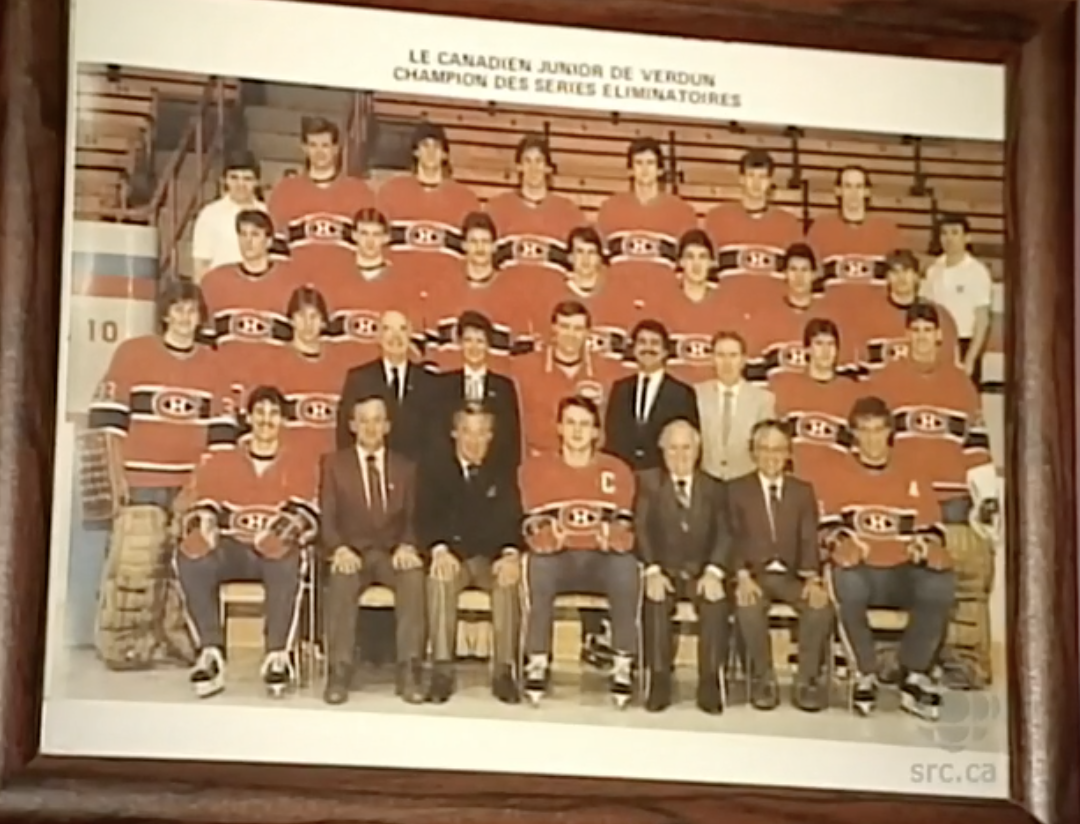

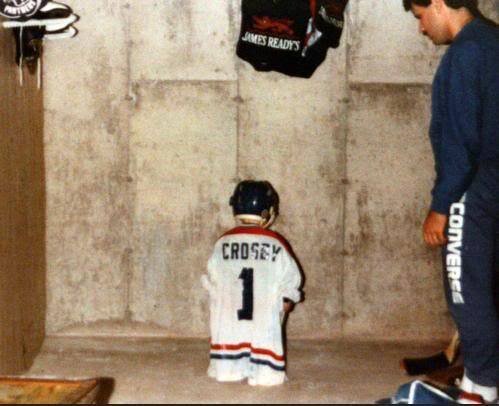

Troy himself had been the Montreal Canadiens’ last pick (240th overall) in the 1984 draft [8, 42]. Sidney grew up a Habs fan—“my whole family is Montreal fans,” he said, “so I guess they pretty much brainwashed me.” While the first NHL playoffs game Sidney ever saw in person was a Canadiens game—Montreal vs. Buffalo, at the Molson Centre—the first game he attended was in his hometown. In November of 1993, Troy’s old junior hockey teammate Claude Lemieux rolled into Halifax with the New Jersey Devils to play a neutral-site game against the New York Rangers. Lemieux looked up the Crosby family in the telephone book to invite them to the game personally [31, 346].

Troy only played for two years in the Quebec Juniors with Verdun, though he had a few memorable nights. He was a “fierce, aggressive Ron Hextall-type of goalie” [11]. In January of 1984 he played against Mario Lemieux in a “breathtaking” performance, but Mario had the last laugh and scored on Troy during a breakaway [373]. After Verdun, Troy was invited to a single summer training camp with the Canadiens before his career died; he was never offered a contract and returned home to play junior A and senior hockey. By the time he played his last season, he had a baby boy named Sidney. He was 22 [8, 42].

“You’ve got a small window to do something you love… for whatever reason that was instilled pretty early. I think that just to appreciate the opportunity you have, and I love the game, so I know at one point it’s gonna stop, and I wanna make sure that I enjoy every minute of it.”

- Sidney Crosby [81]

“I got as high as you can go without getting there. I’ve been through it. So you’ve got to be careful with them. You can’t force them. I think every Canadian child grows up wanting to play in the NHL, but very few do. That was my goal, too.”

- Troy Crosby [298]

Troy didn’t take his loss of hockey easily; Troy’s father had walked out on his three kids when Troy was 7, divorced Troy’s mother Linda when Troy was 8, and never came to Troy’s hockey games. Linda and her children lived on welfare. “My way to succeed was in hockey and sports,” Troy believed, “to show we’re not a failure as a family” [11, 49].

Around the time Sidney was 16, Troy told him about his biological grandfather; when asked about it by the media later in life, Sidney admitted it wasn’t something he liked to talk about. Trina, who lost her own father to a heart attack when she was 11, said “Troy and I both have learned how difficult it is to lose somebody who’s important to you. We have a very strong idea of being grounded” [11]. Both Troy and Trina were the youngest children in their families and were essentially raised by their mothers [Taking the Game…, 40].

After his unfruitful hockey career, Troy worked as an administrative assistant at a law firm; Trina was a cashier at a grocery store [7, 11]. Troy would later say he regretted not focusing more on his schoolwork when he played in junior hockey, as he didn’t have much of an education to fall back on [365]. The Crosby family did not have a large income and struggled to make ends meet [Most Valuable, p. 97]. “Troy and I made sacrifices,” said Trina. “We didn’t go with the best either. We had what we needed and we got by, but we struggled, as a lot of people do” [365]. Sidney’s parents were young when they had him, and they lived with his grandmother Linda Crosby when Sidney was a baby. “There wasn’t a lot of money for extras” [The Rookie, p. 172].

“For me, a lot of stuff wasn’t easy. It wasn’t like I had to work five hours a day to get things, but nothing was really given to me. I was treated well as a kid. I got a new pair of skates for Christmas, but I got what I needed and not a lot more. When it came to hockey, I’d get new skates and a stick. But I learned that you get what you need and not so much what you want. My parents instilled in me that you don’t need everything you see. You work hard for what you get, and a lot of things in life don’t come easy.

“When you’re younger, you don’t even know the difference. Then in junior high when you start seeing kids wearing nicer clothes… I was always more than happy with who I was growing up, but I always felt I had to fight a little hard to keep up.” - Sidney Crosby [The Rookie, p. 172-173]

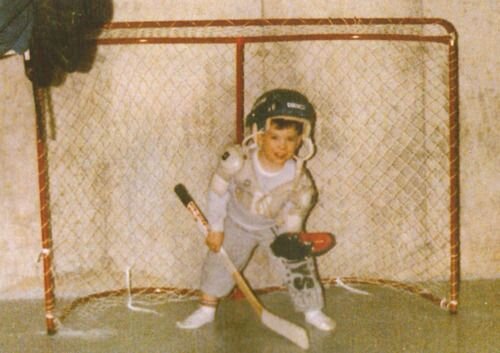

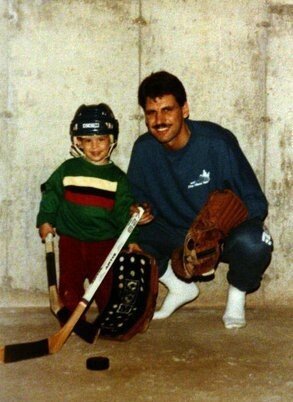

Sidney was always tight with his father. Trina called them best friends, and Sidney followed Troy around like a shadow. Whatever Troy wanted to do, Sidney wanted to do too. Troy would work out in the house with the thought of becoming a firefighter one day [8]. Sidney would later say that if he wasn’t a hockey player, he’d like to be a firefighter [68]. (It likely helped that many of the local firefighters were also often hockey coaches [123]).

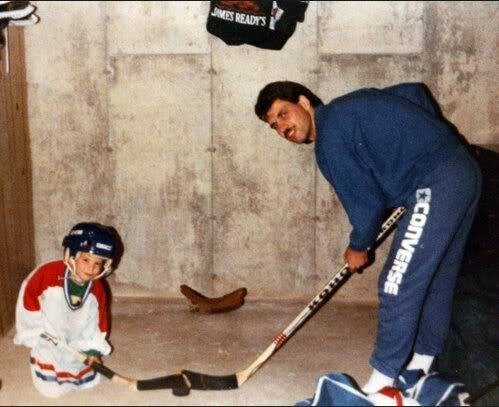

A significant part of their closeness was sport. “The rink almost became a second home for us,” said Sidney. “As a kid, our team had some 5 a.m. practice times, so I was lucky to have parents who made a lot of sacrifices for me. My bond with my dad was especially strong. He obviously taught me a lot about the game but more so [about] life in general” [80]. The game was life for the Crosby family. Troy’s dream of hockey lived on in Sidney.

“It’s in his blood. The ones that have it? You know. I have it; I still have it: There’s nothing I’d rather do more than play hockey. And after I stopped playing, it was... him. I didn’t want to miss a game. I just love watching him play.” - Troy Crosby [8]

Troy was a protective father. “[Troy and Sidney] really are very close...Troy was prepared to go to practically any lengths for his son,” said Carl Fleming, a rival novice hockey coach [Taking the Game…, p. 33]. Sidney, as a hockey phenom, was “vulnerable to a lot of forces that [most] children could never imagine at the earliest of age” [112, 22:00].

“I didn’t see him play, but everything else he did, whether it was fixing a pipe under the house or whatever—he got it done. He wasn’t going to quit on it. If he told me he was going to do something, he did it; if he said, ‘I’m going to bring you to practice today,’ he didn’t call and say, 'I can’t make it.’ He was always there.” - Sidney Crosby [8]

Troy pushed Sidney to succeed in everything from hockey to academics. Troy, who felt that he and other former major junior players hadn’t been encouraged to seriously pursue an education while in the QMJHL, insisted that Sidney prioritize school. Sidney and his parents had a deal: he could keep playing hockey as long as he stayed on top of his schoolwork. It was never an issue according to Trina. Sidney never missed a game or practice. When it came to school, Troy’s concerns for Sidney were often borne from his past mistakes—Troy had shied away from class presentations as a child and never felt comfortable speaking publicly as an adult. Troy encouraged Sidney to work on his public speaking so he wouldn’t have the same fear [40, 365].

Sidney learned to behave and do what was expected of him, and if he was ever in trouble at school, he would be grounded. “I learned pretty quickly at a young age that rules are rules,” said Sidney. “I didn’t miss curfew, and I always was kind of scared of that time when a teacher would have to call home. I tried to be as disciplined as I could” [63].

The “biggest rule in the Crosby house was to give 100-per-cent effort” to anything. “My dad really pushed him growing up,” said Taylor Crosby, “and I think because part of it was that my dad had no one pushing him when he grew up and he had to do it for himself. So he wanted my brother to have someone to help him along the way.” Troy would insist he wasn’t pushing Sidney; he was instilling accountability [49, 62].

“They [Troy and Trina] are both the same in the way they feel about me as a person and a hockey player. No matter what I was doing, whether it was school or hockey, they told me to get the best out of myself and don’t take shortcuts. Don’t take things for granted was the main thing, that’s something that has always stuck with me.” - Sidney Crosby [21]

Though Sidney took after his father’s taste for hockey, he claimed to also get his mother’s keen eye for spotting good people. His parents had “strong senses about things,” and Trina had a talent for whittling down a person to find their angle. “My mom, she’s really sharp,” said Sidney. “On people, she always has the right sense. It’s important, especially in my situation. You have to pick your friends carefully” [The Rookie, p. 94].

“We were lucky. We taught him to be a good person and treat others like he wanted to be treated. It wasn’t complicated. We asked him to treat people with kindness and respect his elders. He’s sensitive to other people. He’s thoughtful.” - Trina Crosby [49]

In 1996, Sidney’s younger sister Taylor was born. The two got along well despite the 8.5-year age difference. “From the time I was little I always looked up to him,” said Taylor. “He really was my best friend growing up” [36].

“He’s an older, protective brother, but he’s not Mom or Dad. We’re close, so I can tell him things I can’t tell them. He will always be the person I turn to if I need help. He probably would still get angry at me if I did something wrong, but he’s gonna always have my back.” - Taylor Crosby [3]

“Our age gap is so big that he was more like a dad to me than a brother. He does have an old soul.” - Taylor Crosby [36]

Sidney was a typical older brother; he was protective of Taylor, but also warred with her over possession of a single fan the two shared. The Crosby family didn’t have air conditioning, and some nights Taylor would go to bed with the fan in her room only to find it mysteriously in Sidney’s room the next morning. He would race her to the car, and if she was beating him, he’d reach out and grab her arm to stop her. Sidney would also tease Taylor—knowing the scene from The Lion King where Simba’s dad dies upset Taylor, Sidney would reenact it in front of her to provoke a reaction. Despite this, Taylor said they never fought much, mostly because of their age difference [36, 62, Most Valuable, p. 77].

“He always says it doesn’t matter what people think, and that those who mind don’t matter and those who matter don’t mind. So that’s kind of the saying that him and our parents put into our heads...” - Taylor Crosby [62]

The Crosby family was large and tight-knit; Sidney learned to love fishing after two of his uncles started taking him out to the water [52]. “We’re just very close to our kids,” said Troy [49]. Being close, consistent, and centered was very important. “We keep him grounded,” said Trina. “We don’t change with him. We don’t treat him differently. He’s Sidney to us. I’m proud of him. He’s a good boy. He’s not perfect, but he’s a really good kid” [49].

Sidney was a good kid, but he wasn’t an average kid. Not all the time, at least. He liked horsing around and playing like a lot of other kids, but things changed when a hockey stick was put into his hands. He once asked why he was the only one in the family who didn’t have a first name that started with a T. “Because you’re special,” his mother told him [37].

She was right.