II. THE KID

Sidney first got in skates when he was three years old.

Nova Scotia’s Halifax Forum was the local rink, “a warehouse-like venue where the pigeon droppings that rained from the rafters to the ice were scraped off with shovels.” Troy would strap double-runner bob skates to Sidney’s shoes and Sidney would take off. He was a natural; his ankles never bowed and when toys were tossed on the ice for the kids to play with, he always went for the plastic hockey stick. “I didn’t have to teach him to hold it,” said Troy. “He just picked it up naturally. I never had to encourage him to play. You could tell he had talent, a gift. He had a passion for the game too” [37, 374].

“He was there for everything. I remember how tight he used to tie my skates. He made them real tight. To this day I still have my skates probably crazy tight because that’s just the way he tied them.”

- Sidney Crosby [374]

Sidney’s passion for hockey leaked into everything. Trina would pick him up from daycare and one of the caretakers would exclaim “I can't play hockey every day!” [270]. His childhood bedroom had Canadiens wallpaper, a Canadiens score clock on his wall, and posters of Lemieux and Gretzky plastered everywhere. Alongside the posters hung a printed quote from Oliver Wendell Holmes, an American Chief Justice. It read: “Make it happen. Greatness is not where we stand but in what direction we are moving. We must sail sometimes with the wind and sometimes against it. But sail we must and not drift. Nor be an anchor” [37, 60].

(Less inspirational, but very cute: Scruffy, the stuffed dog he has had since he was five years old, was usually tossed somewhere in the room. Alongside the posters hung a decorative blue “S” [for Sidney] and a family portrait he scrawled in blue and yellow crayons when he was four [60].)

“It definitely started with me. But then Sidney took it to a whole other level. He wanted everything to be Canadiens, pyjamas, posters, you name it. Sidney’s favorite player was Kirk Muller and he’s had that poster up on the wall in his bedroom for as long as I can remember. [Sidney’s] Canadiens jersey had Crosby on the back with my No. 29 on it. He wore that thing everywhere.” - Troy Crosby [72]

Troy coached older kids when Sidney was still little; Sidney would tag along and follow Troy around the rink, listening to anything Troy would tell him about hockey. Troy gave Sidney “little lessons” about how to act around teammates, team staff, and trainers. It was the little things like cleaning up after yourself, being polite, and treating your space and other people with respect. It wasn’t just about playing hockey; it was about living hockey, and living hockey well [374].

Sidney was always watching his father’s old game tapes [The Rookie, p. 197]. He had a particular interest in Troy’s history with the game—at a young age he developed a fondness for Troy’s binder of old Pro Set hockey cards. While Troy would tell him stories from his time in the Q, Sidney would flip through the pages and seek out Troy’s old teammates in the cards. For Sidney, the hockey cards were a link to the far-off world of the NHL. The Maritimes’ isolation from the league meant the facts on the back of hockey cards were as good as gold to Sidney. Toronto and Montreal “seemed like they were on a different planet,” and checking stats on the back of cards or watching half-hour sports shows on television was how Sidney felt connected to the big leagues [Hockey Card Stories 2].

“My favourite cards were the ones you got at McDonald’s and the ones from Upper Deck. They showed the players out of their uniforms and were somewhat random photos but that’s why I remember them. I remember one of Felix Potvin and his black lab, and Doug Gilmour in his Harley jacket... I remember looking at those cards and thinking I’d never seen pictures of hockey players like that before. Until then, I had only seen pictures of players in action, never out of their gear. So that sticks out from when I was a young kid.” - Sidney Crosby [Hockey Card Stories 2]

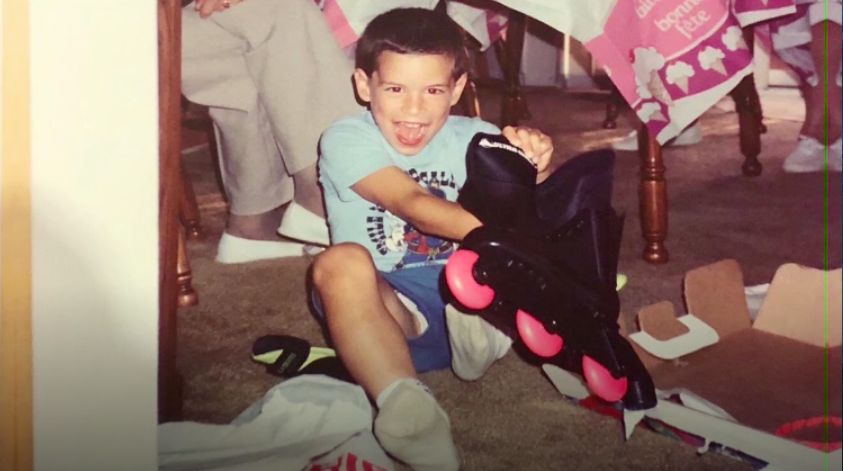

Every night after dinner, Sidney would strap on his rollerblades and grab a hockey stick [60]. All he wanted to do was play hockey, and his family indulged him; Troy would set up stickhandling mazes for Sidney to practice in, or would even put Sidney in goal to shoot on him. “He shot pretty hard,” said Sidney. “I don’t know if he was trying to deter me from being a goalie” [374]. Sidney’s grandmother Linda Crosby would play goalwhile sitting on a chair in the living room (“She was tough to beat,” Sidney would later say, straight-faced). “He shot on anything that would remain still” [Taking the Game…, p. 38, The Rookie, p. 47-48].

Everything was about hockey. Even at Christmas, the World Junior Championship received top priority in the Crosby household, and as soon as all the presents were opened, Sidney would turn on the TV to watch [48].

“Sidney was just Sidney. We didn’t have an explanation as to why God made him like that. He just came to us. He’s competitive and he’s passionate, and that’s the way he is. He loved hockey.” - Trina Crosby [49]

His favorite season was winter, and nothing was better than the feeling of lake ice under his skates. Troy Crosby had a friend with a four-wheeler who could groom pond ice and Sidney’s ragtag group of friends loved to get out on Bissett Lake in Cole Harbour to skate and play. At age 5, Sidney would play shinny for hours [The Rookie, p. 211 & 254].

“The ice wouldn’t always be completely frozen, so when the puck sailed to the middle of the lake, I had to skate pretty fast so I wouldn’t fall through. When a guy came back without the puck, you knew the ice had cracked. One day I’d pretend to be Gretzky, another day, Lemieux... We’d be freezing, but the next day, we couldn’t wait to get back out there.” - Sidney Crosby [60]

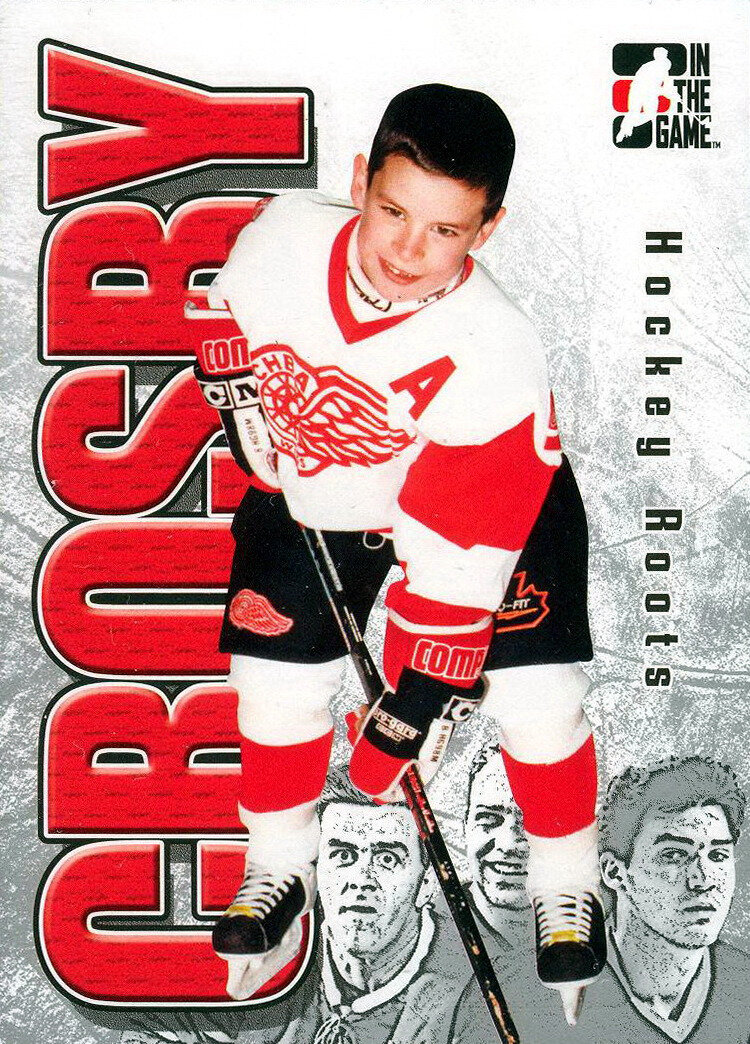

Sidney started playing organized hockey at 4 [21]. By the time he was 5 and wearing #8 in Timbits hockey in Dartmouth, he was already considered a “can’t-miss prospect” [3, The Rookie, p. 48]. His Timbits coach, Paul Gallagher, was in disbelief at Sidney’s skill level and went to the program organizers to double-check that Sidney was only 5 [24]. Troy spoke to Brian Newton, a novice-level coach, over the phone to see if Sidney could be moved up to the 6-year-old novice level [9].

“When he was five or six, you could tell he had something special. Everything came easy to him. That’s not to say he doesn’t work hard at it, because he does, but he was able to do so much more at such a high level. He loves to play. He loves to practise.” - Troy Crosby [221]

Newton, used to these calls from overenthusiastic parents, told Troy that if Sidney was as good as Troy claimed, Newton would be able to pick him out from the other kids. Newton headed over to the rink the following Saturday, and sure enough, he could tell who Sidney was in an instant [9].

“I just kind of hid myself from the parents and out these guys came and he just stuck out like a sore thumb. It was just amazing—I’d never seen anyone with that skill level at five years of age.”

- Brian Newton, Cole Harbour Red Wings AAA novice coach [9]

Sidney was 6, playing with 10-year-olds on the Cole Harbour Novice C's.

Sidney was moved up to the 6-year-old level, and in the winter of 1993, Sidney started playing rep, “a level reserved for the best players in each age group” [9, 60, Taking the Game…, p. 28].

“And I think with Sidney, he always believed that no one cared as much about the game as he did. He believed—and I'm sure he was right—that he always came to the rink more ready to play than anybody else. He had confidence no matter who he was playing against. It didn't matter if they were older, or if they were from other teams and other provinces that had more ice time or whatever. No matter who he was playing against, they hadn't spent as much time practicing and working on their game as he had.”

- Tim Spidel, pee-wee teammate [Taking the Game…, p. 34]

Sidney’s age would be a common refrain throughout his childhood; he maintained an elite level of play while usually being significantly younger than his teammates. There was real risk in playing younger children against older children, and as The Daily News sports editor (and rival novice coach) Carl Fleming noted, Sidney was “so much tinier than the rest of the players who were two to three years older than him. It's not a situation that you’d want to put most kids in, but there was no problem for Sidney... no risk that he was going to get hurt or discouraged. Even at that stage he was capable of doing some amazing things on the ice. He could do things with the puck that the older boys just weren’t capable of” [Taking the Game…, p. 28].

“My whole life, I was kind of the youngest guy on my team. It was kind of unique. I was able to do it and be the youngest, because that was something that was repeated to me a lot. But I was always told that age is just a number.”

- Sidney Crosby [37]

“He was always younger than the other kids and always the smallest kid, but I always told him it’s better to be small and good because if you’re big and good, they’ll always say you’re good because you’re big.”

- Troy Crosby [40]

His skating was superb and his hockey sense was already advanced. Sidney learned very quickly how to make blind passes and how to pass behind his back [3]. “He was 6 [years old] at the time and he could do things that other kids that age couldn’t do, that 8- or 9-year-olds couldn’t do,” his future hockey coach Paul Mason said. “He could make plays and passes where the other kids had tunnel vision. That stood out the most to me at that point. At the same time he had the skill to score” [70]. Troy would buy him hockey videos (with titles such as “Gretzky’s Greatest Goals”) and Sidney would watch them on repeat, absorbing as much as he could [40].

It’s also worth noting that hockey players always have been and always will be gross: “He didn’t like his uniforms to be washed,” Trina said. “I’d just hang ‘em outside on the deck to dry. He loved the smell of those uniforms. He wanted to keep the smell. Everybody else can’t stand the smell, but he and his father, they loved it” [40].

Troy painted the basement to look like a hockey rink and set up a net at one end, with extra netting behind the goal to protect the basement appliances. Despite Troy’s efforts, Sidney still managed to absolutely trash the dryer, streaking it with puck marks and knocking off all the knobs [19]. He even damaged the furnace on one memorable occasion. Trina called the fire department, thinking gas was leaking. It was only hot water, as Sidney recounted defensively. “It wasn’t like I was tearing the house apart,” he said. “That was my space” [60].

“I hit [the dryer] and then I’d hear upstairs, ‘What was that?’ I didn’t say anything. After a while, [my mom] didn’t care. But it took a bad beating.” - Sidney Crosby [3]

There was a television room off to the side of the hockey equipment that had eaten up much of the basement. Troy would sit and listen to the sound of Sidney’s roller blades on the concrete, or would feed passes to Sidney to work on Sidney’s forehand and backhand. “It was one of those things, that is where we spent a lot of hours. Thousands of pucks have been shot down there, thousands. In some small way, they’re all pieces of the puzzle” [61].

Some thought Sidney’s consuming focus on hockey was the product of Troy’s own obsession. According to Tim Spidel, one of Sidney’s old teammates, Sidney’s desire for things to be all hockey all the time was innate. “Sid always wanted to play,” said Spidel. “Always. Every hour that he wasn’t sleeping or in school he’d be doing something with hockey in it.” Sidney didn’t invite friends over to play Nintendo or watch TV; he invited them over to help him tear up the basement or shoot pucks out on the street. “That’s the thing with Sidney when we were coming up. I don’t think that we ever looked at it like it was work or a grind—he just made a game of what we were doing. He ‘played’ hockey like it was play, like it was something to have fun with. And I really think that we did and that's why we never got tired of it” [Taking the Game…, p. 34].

“People would say I had him shooting 500 pucks and doing 200 pushups. It was ridiculous. He was competitive.”

- Troy Crosby [49]

“You can't really look too far ahead. There's so many things that can happen. Some kids are late bloomers. The worst thing you could probably do is pressure him too much.”

- Troy Crosby [298]

Eventually, Troy had to relinquish goaltender duties for Sidney when Sidney was 7—he had started shooting at Troy’s shins [3]. “He was killing me,” Troy said. “I told him, ‘You don’t need a goaltender, just shoot at the net.’” According to Troy, Sidney had a penchant for taking full wind-up slapshots [Taking the Game…, p. 38].

“I had a little bit of talent, but talent is nothing without hard work. My dad was supportive and gave me little tips. Along the way, I absorbed everything I could like a sponge.” - Sidney Crosby [182]

Sidney’s athletic ability wasn’t limited to hockey; Trina said he had the form of a 20-year-old when he threw baseballs, and “when it came to motor skills, he could do everything.” One of the lifeguards at Sidney’s YMCA preschool told Trina “I’ve never seen a four-year-old with developed pecs before” [8]. When he grew older, he’d eventually play football, baseball and tennis [1, 5:22]. Despite his athleticism, he was still just one of the kids most of the time. “He enjoyed his little box of juice after the game just like all the others” [24].

When he wasn’t playing hockey, Sidney “enjoyed playing POG, watching Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and play-wrestling with friends, hurling himself off furniture, like his idol Bret ‘Hitman’ Hart” [60].

“Troy needed the hockey bond with Sidney, so I needed my own thing to be close with him. So I’d take him to puppet shows, the Ice Capades, or we’d put on our raincoats and boots and jump in puddles. Maybe that’s why he’s so balanced, because it wasn’t always about hockey.”

- Trina Crosby [60]

“When he was six, Sidney and I would play hairdresser. One day we were driving to practice, and he said, ‘Dad, I don’t know if I want to play in the NHL or be a hairdresser.’ If you could’ve seen the look on Troy’s face! Shocked, he said, ‘Well, Sid, uh, you don’t have to make any snap decisions just yet.’ We didn’t play hairdresser anymore.” - Trina Crosby [60]

Sidney attended Colonial John Elementary School, Colby Village Elementary School (whose mascot was a penguin [54]) and Astral Drive Junior High. He had a “huge circle of friends” according to Astral Drive Junior High Vice Principal Karen Dale [124, 198]. In his own words, he was a “decent” student (though one article claimed he was an honors student [288]), and his parents pressed him to work hard in school. His favorite subjects were history and math, and his least favorite was science [68]. He was also very strong in family studies [61].

His love of history came in part due to the hours he would spend volunteering at a local hospital for veterans where his aunt worked. Some of the veterans there loved talking about their service, and Sidney was an avid listener [52].

He was bad at art, dance, and music, barely passing the recorder unit in school. Despite this, he inexplicably starred in a school play. Trina’s mother, Catherine Forbes, said “He’s so handsome. I betcha he’s going to be on the soap operas one day.” Trina had break it to her mother that “He won’t, because he can’t act” [60].

“He can't dance. God love him, he's a wonderful boy, but he can't dance a lick.” - Trina Crosby [270]

Even at school, Sidney found a way to focus on hockey. As a part of an elementary school project he wrote “letters to the Philadelphia Flyers asking for autographed hockey cards and photographs” [The Rookie, p. 120].

"People at school talked about it—you know, he's always playing hockey. There would be the normal school things that he'd miss because of hockey. Because it was sports, people didn't think it was geeky.” - Tim Spidel, pee-wee teammate [Taking the Game…, p. 34]

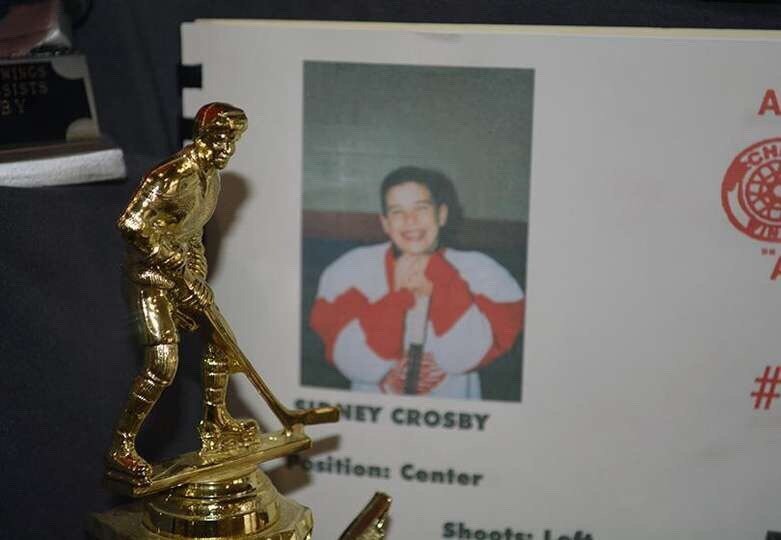

In novice hockey (typically for players under 9 years of age), Sidney realized he had a “special talent” of some sort, and the media noticed too [21]. He was interviewed by a newspaper reporter for the first time in 1994, at age 7 in the Cole Harbour community hockey rink just outside of Dartmouth [19, 38, 39].

Charlene Sadler, the reporter, took note of his skill, calling him “nimble and sure-footed,” but also pointed out that he was “noticeably smaller” than the other children on the ice. He was the youngest player there by at least two years. Even so, he “dominated” [39].

“I interviewed the future star in the changing room. He was so little and was as cute as a bug. His feet didn’t touch the ground and he swung his legs back and forth during the interview.

“I asked him if he hoped to make it to the NHL. He was polite and soft-spoken and thoughtful with his answers. There was no seven-year-old bravado or delusion of greatness.

“‘They say you have to do your best and work hard and things will happen. You can make it if you try,’ he said.” - Charlene Sadler [39]

“It was very cute. I went out to get the car, and I thought we were going to be, like, five or ten minutes, you know? And I was out in the car, and I was kind of ticked off because they were taking so long and I wanted to get home.” [She went back inside and found Sidney sitting on the bench, yakking away with the reporter.] “It was just so cute. His feet weren’t touching the ground.” - Trina Crosby [46]

Trina marked novice as a shifting point for her and Sidney’s relationship, implying she was more of an observer, “that the passion Troy and Sidney shared for the game, and their shared competitiveness, set them apart from her at an early age. ‘Probably when Sidney played novice, I lost them. I just made sure he got fed,’ she said” [61].

As a 7-year-old, Sidney’s team had two practices and one game each week, but hockey was a constant affair for him. Sidney would always be playing road hockey with his friends—according to him, “There weren’t too many days that went by when we didn’t play hockey. We had lots of kids in our neighborhood and we always wanted to play hockey. We played ball hockey a lot and I’d also play hockey in my basement. I tried to play every day because I love the game” [91].

“Right now, Sidney lives for hockey. This week, it’s the SEDMHA tournament. After that, he joins the Nova Scotia novice AAA select team, travelling around the Maritimes to play the best each province has to offer. Then summer hockey camps start up. For him, hockey is not a seasonal sport: it’s continuous. Hockey in the basement, hockey in the street, in the driveway. Hockey all the time.”

- Charlene Sadler [298]

Sidney was intense; he was “consumed by winning. Not just at hockey. Not just in sport... there was something deep-seated, almost needy, about his attitude toward victory and defeat.” According to his former childhood teammate Andrew Gordon, Sidney would be “ruined after a loss—nothing you could say could pick him up” [Taking the Game…, p. 35]. Any missed chances he had during games would eat at him. “I don’t know if you call it a mistake, or you call it something you wish you could do over again, but yeah, he’s always done that,” said Troy. “For a long time he’s done that, ever since he was a kid. For as long as I can remember” [97]. He turned everything into a competition, even betting who could finish their meals first. If he lost, he’d bet again: double or nothing [Taking the Game…, p. 35].

“Once when Sidney was very young, we were driving home from a game and he started complaining about a mistake a defenseman had made. Troy turned to him and asked, ‘Do you think you were perfect today?’ Sidney said, ‘No.’ Troy told him to just worry about himself and never mind what others do. Sidney got the message.” - Trina Crosby [270]

Also at age 7, Sidney “began attending a... hockey camp for the top players in the Maritimes” [The Rookie, p. 48]. Held in Charlottetown on Prince Edward Island, the program was a “prominent hockey school” and usually drew older players [114]. Brad Richards, another future NHLer, was an instructor at the camp and saw Sidney there four or five years in a row [The Rookie, p. 48]. Even though Sidney was seven years younger than Richards, Richards was impressed by how Sidney was a “sponge” regarding hockey. Sidney talked hockey constantly and played so well that in his later years at the camp—ages 13, 14, and 15—he was selected to play in showcase games with NHL players [114].

“You see a lot from a lot of kids early, but he was different. Even the way he put his equipment on was different. He was already professional in the way he carried himself. Even at that early age, you could tell he was special, head and shoulders above everyone else his age. He never stopped learning, he just kept going. Kids usually peak. He never did.” - Brad Richards [The Rookie, p. 48]

Sidney’s coach on the Cole Harbour Novice AAA Wings, Brian Newton, said his focus was to make sure the kids had fun, but AAA novice was still a competitive level. The parents acted like it, “booing the refs, jeering the opposing coaches and screaming at the players” [39].

Newton considered Sidney to be the best player he had ever seen, and that accolade was bringing Sidney attention [9]. Nova Scotians who lived hours away were hearing about a kid down in Cole Harbour who was “going to be the Next One” [70].

Not all the attention from Sidney’s rising star status was positive. During the provincial playoffs, an 8-year-old Sidney scored five goals in a game. After one of the goals, an adult fan “leaned over the glass and began yelling, ‘Go home Crosby, ya bum! You’ve got no skill!’ On another occasion, young Sidney left the arena in tears after a woman called him a ‘prima donna’ in the arena lobby. His parents had the job of not only driving their son to the rink, but too often consoling him during the ride home” [45]. Strangers repeatedly talked down to Sidney about his skills and his size [49]. When Sidney’s coach told Troy that parents were no longer allowed in the locker room, it not only “devastated” Troy, who cherished the time he got to spend helping Sidney suit up; it worried him. Troy could no longer act as a shield for Sidney in the locker room [60].

“I don’t know if jealousy is the right word, but there was definitely a lot of resentment. Maybe not with the kids, but with the parents. At one point, it was very hard to go to the rink if there had been a big article about Sidney in the newspaper.” - Trina Crosby [45]

“Sometimes there was nothing said, but you still felt it. Something like that happened every year and it got worse. There were so many comments. People said Troy pushed him too hard. It wasn’t everyone, but there were a lot.” - Trina Crosby [49]

Former CBC sports broadcaster Bruce Rainnie heard about Sidney in 1995, and though he was skeptical, he decided to see what the buzz was all about when Halifax sports writer Pat Connolly told him to watch Sidney play. The night Rainnie came to watch, Sidney recorded nine goals and two assists in a 13-9 Cole Harbour win over Shearwater [9].

“I thought if he develops into any sort of average to larger-sized athlete, this is going to be an NHL legend. And it was obvious from, honestly, the age of eight.” - Bruce Rainnie [9]

It was obvious not because of personal impressions, but because of the numbers Sidney put up. In atom hockey (typically ages 9-10), Sidney scored 159 goals in 55 games and finished the season with 280 points. He was 10 years old [43].

His success only riled up the crowds more. He heard derisive taunts and cruel words, to the point where he “would go out for the pregame warmup without his hockey jersey to avoid detection from rival fans” [45].

“It’s nothing new for me—it didn’t just start this season. I’ve been dealing with this since I was 9 or 10, guys shadowing you and saying stuff.” - Sidney Crosby [72]

Despite this, his love for the game still burned strong. He would wake up before dawn and skate with Troy until other teams rolled in to start their practices. Carl Fleming, a rival novice coach, recalled seeing Troy and Sidney out on the ice before Fleming’s 6 a.m. practices [Taking the Game…, p. 33]. Another of Sidney’s coaches, Dennis Irwin, remembered having to “beg to get [Sidney] off the ice” [24].

Hockey was a group activity for Sidney. As much as he hung out in his basement, ruining the family’s dryer, he was always trying to rope friends into playing with him. “With Sid,” his childhood friend Mike Chiasson remarked, “you knew you were always going in his basement to play hockey, have a shootout.” On Saturday mornings, he was known to call his friends’ houses at unreasonable times, asking if they were awake and up to play street hockey [8]. Sidney always played goalie because he was too good for any other position [61].

“We’d have practice in the morning, and he’d want to play road hockey in the afternoon. Hockey, hockey, hockey. He was pretty much born on skates.” - Mike Chiasson [11]

“I always picked him as my goalie or tried to get him. If I had him in my net I knew I had a better chance at winning. We played the World Roller Hockey Championship, which was by no means the ‘World’ Roller Hockey Championship. It was six teams from Cole Harbour. I went with all young guys. He was my goalie. We were the underdogs and pulled off the victory. We picked the right goalie.” - Jeff Kielbratowski, childhood friend [71]

“Whatever we were doing he always wanted to make it a competition or a sport. It hasn’t changed since the time he was 6 or 7. It was always a series or championship on the line. I guess that’s why he is where he is today.” - Mike Chiasson [71]

“I played as much as possible. Whether it was organized games in a league or shinny at our local rink. I grew up in Cole Harbour. We were in a row of townhouses and there was a bunch of us who always played together. I’d knock on doors after school and on weekends, trying to get guys to come out to play. And we had a really good bunch of players. We called it ‘our dynasty.’ We won a lot of championships.” - Sidney Crosby [Most Valuable, p. 96]

Sidney’s friends were a tight-knit group. They played several sports together, from hockey to baseball, so they were teammates year-round. Sidney was involved in a swath of sports, always on the go [60]. He played on the Cole Harbour Cardinals baseball team until he was 14, where was coached by his future hockey coach Paul Mason [69, 70]. He was usually a third baseman and pitcher, though he also liked to play catcher because he enjoyed being constantly involved in gameplay... and he “liked having the game go the way [he] called it” [Taking the Game…, p. 97].

In the Mosquito A baseball Atlantic Championship (the Canadian equivalent of Little League Baseball), Sidney was pitching and his friend Mike Chiasson was catching. Sidney pitched 5 of the 6 innings before being pulled—“He ran into some control issues in the sixth. We had to yank him in the sixth and I never let him live that down,” said Chiasson—and the Cardinals just barely held on to win the championship [71]. The Cardinals won the Atlantic championship in the two seasons Sidney played with Mason and Chiasson [70, 357, 358]. Their 1997 season was particularly stunning; their team of 12 Cole Harbour natives won 49 of 56 games and won all 5 Maritime tournaments they entered by winning 25 games straight. That year, Sidney was named Tournament MVP at the PEI Tournament in July and All-Star third baseman at the Atlantic Championship [358].

“The ball team won every game in provincials by the 10-run rule and went undefeated in all tournament play. It was almost unfair. We lost four games throughout the whole year. That year we had six no-hitters from different pitchers, [Sidney] was one of them.”

- Paul Mason, Cole Harbour Cardinals coach [70]

Sidney was nearly scouted for professional baseball, but was too young and pursuing hockey instead [82].

“...we had a real shot at playing in the Little League World Series when I was a kid. We were that good. It didn’t happen though. I had to give up [baseball] and concentrate on hockey and I was pretty sad about that—I really loved the game. I still wish I could play.” - Sidney Crosby [Taking the Game…, p. 97]

Outside of sports, Sidney and his friends got into run-of-the-mill childhood trouble like scamming the local mini golf course so they could play the course twice for only a dollar, or boxing on the back of Matthew Foston’s deck until Sidney lost a tooth [71]. They enjoyed going to flea markets in Cole Harbour, the Penhorn Mall in Dartmouth, and the Civic Centre in Halifax to barter with hockey card dealers. Sidney once got fleeced and traded away his Mario Lemieux rookie card for a set of trophy cards, including a Stanley Cup card [Hockey Card Stories 2]. The Crosbys also hosted Tomáš Sedlák, a teenage Czech hockey player, while he attended a Halifax hockey camp for a summer [117].

“We would have sleepovers at his old spot, Trina making pancakes in the morning.” - Matthew Foston, childhood friend [71]

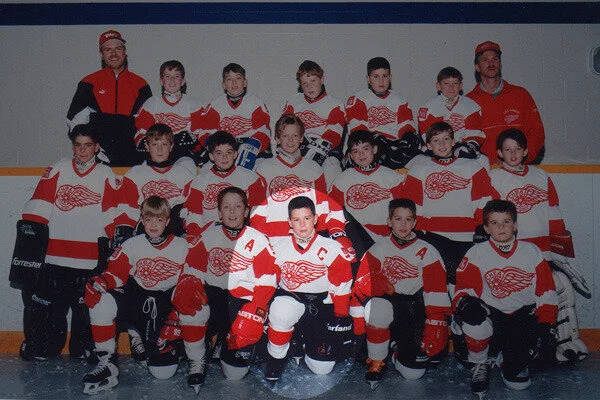

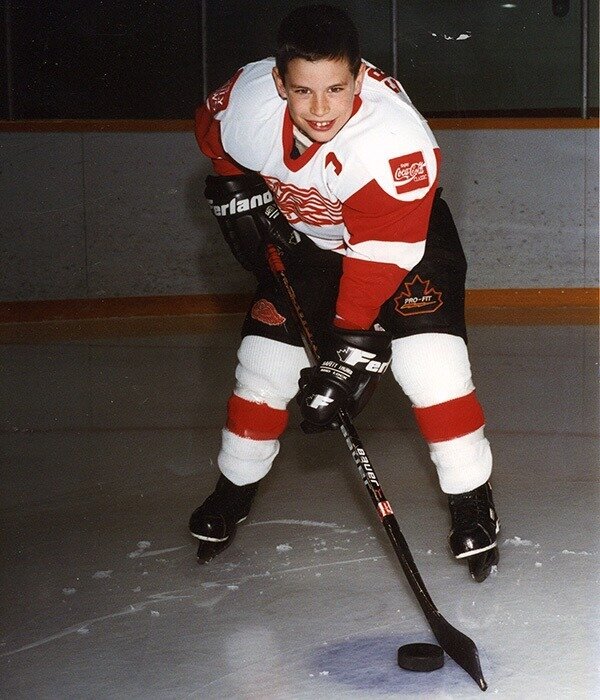

In pee-wee hockey (typically ages 11-12), Sidney continued to impress. He joined the Pee-Wee AAA Cole Harbour Red Wings at age 10, and his old baseball coach Paul Mason became his hockey coach. Mason had watched Sidney grow up as a hockey player and claimed that he knew from the moment he first saw Sidney play at 6 years old that Sidney would be an NHL player. Sidney was incredibly competitive, and “hated to lose more than he liked to win” [70].

“He was underage, but he was the top player... He dominated and every team knew that he was the player you had to stop... We said it jokingly, but we weren’t joking, offensively you almost couldn’t coach him at pee-wee because he saw things that you didn’t see. What he could see live during the play was different than other kids. You could teach him some things defensively or system plays, but you couldn’t restrict someone with that ability at that age.” - Paul Mason, Cole Harbour Red Wings AAA pee-wee coach [70]

Paul Mason was also a family friend of the Crosbys; he would drive Sidney to and from practices and games, and Sidney’s first car accident occurred during one of these trips. “I lost my eye and it was only a couple weeks after and I pulled out in front of a motorcycle. I remember Sid’s mom was losing her mind,” Mason laughed [70]. Trina and Mason had a playful relationship that involved the occasional prank, the most memorable of which occurred in Charlottetown, P.E.I. The team was competing for the Atlantic title and was celebrating at a restaurant after making it past the semi-finals. Mason roped a waiter into delivering a bowl of ice cream to Trina. The catch was that the ice cream was topped with Mason’s fake eye [380].

When he wasn’t pulling a fast one on Trina, Mason did his best to coach her prodigious son. Mason points to an instance at Cole Harbour Place on the Scotia 1 rink as proof of Sidney’s skill; Sidney had the puck below the goal line and was trapped without a clear pass to any of his teammates. He banked a pass off of the net to his teammate, Corey Manfield, who was perfectly positioned in the slot. The puck landed right on Manfield’s stick and he put it home. “We looked at each other on the bench. We’ll never forget that,” Mason said. “We talked about that for years. I’ve never seen that done at any other level” [70].

“He had vision beyond vision. My assistant coach and I used to look at each other and say ‘Did he do that on purpose?’” - Paul Mason [24, 54]

Despite his small stature (in comparison to the boys he played against), Sidney was like “an adult playing with kids” according to Darren Cossar, the executive director of Hockey Nova Scotia. He possessed control, vision, and an iron-fisted grip on the concepts of hockey. The puck “seemed to follow him or always be around him” because of his ability to read other players and predict where the puck would be before anyone else. “It was as if he knew where the play was going and what the other kids were thinking” [The Story of…, p. 8].

His skill was so great that he often found himself stifled by his teammates. Though he was coachable, he would get into a rut when his teammates couldn’t play up to his level. “He’d be frustrated that no one else could think like him and keep up with him,” said Mason. It meant the coaching staff had to find increasingly creative ways to use Sidney on the ice. “I remember telling him—he was getting frustrated once, playing Halifax, on the bench. They had two guys on him, and I said, ‘Sid, skate out in the neutral zone,’ and two guys would follow him out. We had a power play, it was 5-on-4, he’d skate out, and we now had a 4-on-2” [380].

The Cole Harbour Red Wings attended the Quebec International BSR Pee-Wee Tournament, where hype was growing around a kid from northern Quebec. “The people said he was this special kid, so we went to watch him,” Mason said. “I remember saying that we have a kid as good as him, if not better, and he's not even pee-wee age” [70].

“From the time he was a kid, he played up to the competition. I told him to always challenge yourself to be the best. Don’t settle for being ordinary. That was just my philosophy.” - Troy Crosby [37]

Sidney, once again competing against children two or three years older than him, had a dominant showing at the tournament. In his first game, Sidney put six goals and four assists on the board. The modest media hype around him exploded [9]. When the team returned to Cole Harbour, Mason fielded calls about Sidney from all over the country and beyond, including one from the Czech Republic [167].

“Even on a Thursday night in Cole Harbour there might be more people that would show up than would normally be there, to have a look. Everybody’s interested, everybody was inquisitive to try and figure out, y’know, have a look at the kid.” - Trina Crosby [228, 3:50]

Once again, the attention brought negative consequences. By the time he was 11, “he’d sit in the stands during tournaments while waiting for his team’s turn to play, wearing shoulder pads but no sweater; too often parents, seeing the name on his jersey, had jeered him to the point of tears” [8]. Sidney struggled to understand why it was happening, and his parents struggled to cope with their son being the focus of criticism and bullying. Troy and Trina were still young; “We didn’t have enough life experience to understand that you can’t make everybody like you,” said Trina [365].

“But back then to hear people criticizing Sidney, it just felt like it was to be hurtful because you’d think ‘My God, he’s 10 years old, get a life.’ I mean, who knows or who cares if he’s going to be six feet tall, he’s having a ball right now and he’s doing well so why can’t we move forward with that. But lots of times you’d be in the rink and somebody who was standing a foot away from you who didn’t know you from a hole in the wall would start saying things like ‘Wait until he gets to the next level, they’re going to pound him. He’s never going to be anything.’” - Trina Crosby [365]

“In arenas, when he’d watch the game before his, people would recognize him and yell out his name. To be that popular is overwhelming for an 11-year-old. He thought he was a freak. So he stopped wearing his jersey so people don’t recognize him. All that attention was hard on him.” - Troy Crosby [60]

Around this time, his parents noticed that he was “passing the puck more than usual, not skating as fast, not scoring as often. He was playing down. It dawned on them: Sidney was trying to fit in” [60].

Even when he tried to fit in, he stood out, and standing out wasn’t something his peers always appreciated. Though the words from the parents hurt, it was the other children that posed a more direct threat to Sidney. “I remember being in pee-wee, a guy trying to break my leg,” said Sidney. He gestured as if he was swinging a stick. “It wasn’t even during a play: I was going to a face-off, and a guy just two-handed it right at my knee—like a baseball bat” [8].

“It’s been like that since I can remember, since pee-wee, atom. There’s been a guy shadowing me or guys taking runs.” - Sidney Crosby [20, 10:18]

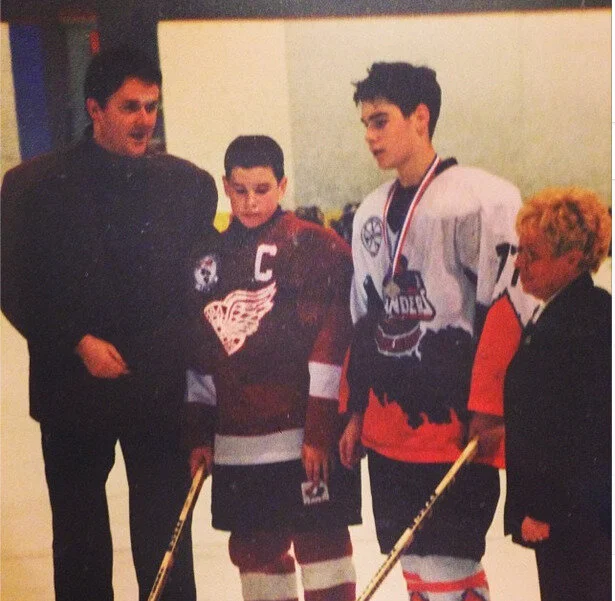

In 1999, Coach Harry O’Donnell of the Cole Harbour Red Wings AAA bantam team decided to play Sidney in the Joe Lamontagne Memorial March Break tournament. Sidney was 12 years old and “playing up” against boys as old as 15. “Playing up” is a point of debate in youth hockey and rarely does young players much good—it’s often considered more a sign of overly-ambitious parents than proof of extraordinary talent. Sidney, however, had been playing up his entire life, and had just led his own team to the Atlantic Pee-Wee Championship in Fredericton the previous weekend [258, Taking the Game…, p. 41].

When Sidney was asked how he was able to advance his game so quickly, he shrugged off the idea that his obsessive focus on practice was a hardship. “Yeah, I mean, it’s not like work,” he said. “I’m just observant when I’m watching hockey. I always want to learn new things. It’s something that I absorb quickly.” He equated his ability to pick up hockey skills to how some of his classmates were inherently good at certain subjects in school—“[Hockey] is something that I seem to know.” Sidney would constantly be watching the older players and taking note of their skills and moves. If they were doing it at 16 and he was able to figure it out by 12 or 13, he reasoned he’d be ahead of the game creatively. Better yet was when he’d be able to take what he learned from other players and make something new [357]. His attention to detail and his innate hockey skill meant that he often looked more at home playing against older boys than kids his own age.

“It was Sidney’s goal to be the best. It wasn’t about being a puck hog. It wouldn’t have been fair to ask him to play down to other players.” - Troy Crosby [49]

Playing up starts having material consequences as players get older. When a 6-year-old plays with 9-year-olds in a no-contact league, there’s not much risk. When a 12-year-old plays against 15-year-olds in a bantam tournament that allows body checking, age matters [Taking the Game…, p. 41]. Sidney was 5’2” and 130 pounds at the time—significantly smaller than many of the bantam players at the Joe Lamontagne Memorial March Break tournament [258].

Though he was small, Sidney had a wonderful showing, netting a goal and three assists in the team’s 10-0 win over the TASA minor hockey team. His success brought him attention and then consequences; the Cole Harbour Hockey Association’s age rules prohibited a player as young as Sidney from playing in a bantam tournament. O’Donnell was suspended by the CHHA for the first game of the Irving Oil Challenge Cup, Atlantic Canada's AAA bantam championship, as a punishment for playing Sidney, and Sidney was denied the ability to play in the championship, which would have been a “personal showcase” for him in his hometown of Cole Harbour [258, Most Valuable, p. 43-44].

“I think it’s pretty cheap, because Brent Theriault [another pee-wee-aged player] will be playing for the Halifax Hawks, and I can’t play. I wanted to finish my season this weekend playing in the bantam Atlantics, but now I can’t. It’s just politics, I guess.” - Sidney Crosby [258]

In interviews with local media, Sidney rebuffed the notion that checking and potential injury were serious concerns: “It’s no big deal,” he said. “I played with those same guys most of last year. It wasn’t that hard. After the first period, I was pretty well used to it” [Taking the Game…, p. 42]. Sidney estimated he’d played around 80 games with checking at this point. His father Troy was rankled by the association’s flat refusal to let Sidney play, arguing that bantam hockey was the best option to continue Sidney’s development as a player. “Everyone should be challenged to play at their best,” said Troy, “otherwise it’s just a waste of time” [258].

Questions emerged over the CHHA’s age rules—in the previous season, several boys played up from pee-wee to bantam. In the offseason, the CHHA had tightened their age requirements. That the new rules would hold back Sidney, who had been garnering media attention for years, must have been obvious to league officials. “In fact, some [people made] the case that it was a change in policy made with [Sidney] in mind, and it had to be hard for him not to take it personally” [Taking the Game…, p. 42].

Troy appealed to the Cole Harbour officials but was denied a meeting. The officials were skeptical of Sidney, overlooking that he’d already played a season of full-contact hockey and racked up over 200 points in 70 games while doing it. Fellow players thought Sidney could handle the pressure: “He was stronger than some of the biggest guys on the team—on his skates he was stronger than practically anyone. Nobody who played against him—no matter how big or how much older—thought that he was easy pickings or anything like that,” said Chad Anderson, who played against Sidney from novice through bantam. The officials were uninterested in what Sidney’s peers thought. Officials didn’t see a plucky prodigy when they looked at Sidney, but rather a boy playing against teens who clocked in at over six feet tall [Taking the Game…, p. 42-43].

“Whenever he was playing up—whether he was 6 or 12 or whatever—he just seemed to know how to act around the older guys and he knew what to say. He didn’t make it seem like he had to try to do that. He just knew and made it seem natural. No one ever objected to having him around—you had to respect his game and you had to respect him just for the way he is.” - Andrew Gordon, former age-group teammate [Taking the Game…, p. 44]

Despite the Crosby family’s efforts, Sidney was denied entry into the bantam tournament. CHHA officials refused to explain their decision, even though pee-wee-aged players from other Maritime leagues were participating in the championship. The CHHA president declared it an “internal” matter, turned away interviews, and hung up on locals who called to plead Sidney’s case [Most Valuable, p. 43-44].

The media attention on the family began to grow, particularly on Troy. He was “not always well respected,” and one local columnist said he was “no angel” [Taking the Game…, p. 44]. Another suggested that “[some] of the criticism directed at [Sidney] might be misplaced anger from those who object to Troy’s behaviour in the stands” [Most Valuable, p. 43].

“Some of the stuff that Troy and Trina had to put up with at the arena was awful. There were lots of awful things that were said to him and his parents by the parents of other players. It had to make them very uncomfortable—it certainly did with Trina. And Troy had to take the role of looking out for Sidney. It wasn’t just Sidney’s playing up. [Troy] looked out for him in a lot of areas—whether it was teams coming after Sidney or agents or whatever. And Troy had to be firm and sometimes tough in looking after Sidney’s interests.” - Ed Spidel, father of teammate Tim Spidel [Taking the Game…, p. 44]

Sidney was hungry for more hockey and more challenges. If he wasn’t careful, though, the hockey world would take a bite out of him too.