III. THE PRICE

By the start of the 2000-2001 season, Sidney had turned 13 and was eligible to play bantam hockey. Before the Cole Harbour Red Wings AAA bantam team opened their tryouts, though, his focus slid up a level to midget hockey.

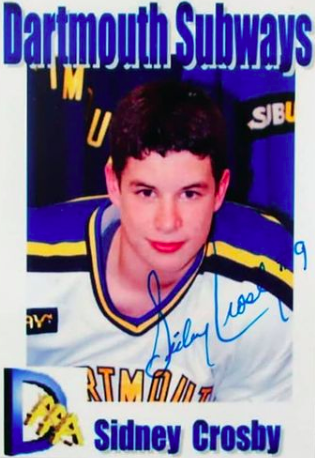

The Dartmouth Subways AAA midget team was hosting practices, and coach Brad Crossley invited Sidney out for a test run [287].

Then the hammer came down.

Sidney had been practicing with the Dartmouth Subways at their training camp for only three days (and had scored four goals and an assist during an intrasquad game [288]) before he was ordered off the ice on August 17, 2000. Keith Boutilier, the Dartmouth regional director of the Hockey Nova Scotia Minor Hockey Council, threatened Crossley with disciplinary action if he continued to allow Sidney to play or even practice with the Subways. Crossley had not followed the Nova Scotia Hockey rules, which state that for a player to jump two levels, there must be approval by the minor hockey council [287].

“I’m getting sort of tired of it. I wish they wouldn’t think so much about age. I was taught all my life age is just a number and to always shoot for your best. That’s what I’m doing and they just keep putting me back down.” - Sidney Crosby [288]

Sidney, his parents, and Crossley met with the council in a closed meeting at the Annapolis Valley Inn on September 24. The meeting did not go well: “The reception that we got down there was despicable,” said Trina. “Every one of the people on that board should be ashamed of themselves. We left no rock unturned. But they weren’t even listening to what we were saying. They looked very disinterested. We thought we had a legitimate opportunity for him to be allowed to play. But it was a formality, really. They had absolutely no intention of allowing him to play” [293].

Sure enough, a day later the council informed Sidney that his bid to play midget hockey had been rejected. In its letter to the Crosby family, the provincial council wrote: “[We] recognize that Sidney is a very talented young man, but do not believe that it is in the best interests of his growth and development to approve such a move. Therefore, I regret to inform you that approval was not given to allow Sidney to move from pee-wee AAA to midget AAA” [293].

The Crosbys were not so easily deterred—“From the time Sidney started playing minor hockey he’s always been fast-tracked and always played an age level above,” said Trina, who believed the Subways would be a “wonderful stepping stone” for Sidney to grow his hockey: “By Christmas, he would be someone to reckon with,” she said. “We don’t see him riding the bench” [288].

Sidney did not attend the bantam tryouts when they opened, and the Crosbys mounted an appeal to Hockey Nova Scotia. “[Sidney] wants us to follow every avenue that’s available to us,” said Trina. “That’s what we're going to do” [293]. It escalated to the point that the Crosbys sought a civil court order to allow Sidney to play [Most Valuable, p. 44-46].

“A bunch of us went to bat for him to make the case that he wasn’t just good enough to play, but he was going to be a dominant player at that level.” - Paul Gallagher, Cole Harbour Red Wings Bantam AAA Coach [Most Valuable, p. 44-46]

During the court case, Sidney was barred from playing hockey entirely. For six weeks he sat on the sidelines while his parents and community tried to convince Hockey Nova Scotia that he could play midget AAA hockey. “It was cruel what happened to him,” Troy said. “He was treated like a criminal” [42]. Finally the decision came: Sidney would not be permitted entry into the midget league, and would instead return to his bantam team to be coached once more by his old Timbits coach Paul Gallagher [24]. “Our next step would have been the CHA, but we’re not going to bother,” said Troy. “They’re all going to say no. They aren’t going to overturn a decision of one of their branches. It would have been a waste of money and a waste of time” [266].

“I would have been challenged in midget. I'm still going to get better, but I think I would have improved a lot more in midget.” - Sidney Crosby [266]

After a month and a half without playing in a hockey game, Sidney laced up his skates for the Bridgewater bantam tournament. He scored 20 points in 5 games and led his Cole Harbour Red Wings to a tournament victory [266].

“I said ‘All set?’

“[Sidney] said ‘Let’s get ‘er going.’”

- Paul Gallagher, Cole Harbour Red Wings Bantam AAA Coach [24]

His dominant play at Bridgewater seemed like blatant evidence to the Crosbys that Sidney had progressed past bantam-level hockey. “[Bantam is] not bad hockey,” Troy said. “That’s not the point. He has a talent to play at [the midget] level. I don’t think it was fair. We tried our best, that’s all we can do. Politics sometimes interferes” [266].

“The Crosbys lost but the one who seemed to take it best was Sidney. When he showed up for practice [with the bantam team] after the court decision, I took him aside. I wanted to make sure he was in a good place about it. It would have been tough to handle anything like that, and especially if you’re 13. But what I love about Sidney, he just looked at me and said, ‘It’s okay. Let’s just go win the championship.’ And that’s what we did that season. We ended up winning the Atlantic Canada title with him that year, and I’ll never forget the goal in overtime. He set up the goal with a pass between the defenseman’s legs to get the winner. Andrew Newton scored it. Did [the court decision] bother him? I’m sure it did. Did it affect his play? Not for a second.” - Paul Gallagher, Cole Harbour Red Wings Bantam AAA Coach [Most Valuable, p. 46]

Before bantam, Sidney had only been able to practice twice a week and was largely a local phenomenon. Though locals had started hearing about him and even travelling to watch him play, Halifax wasn’t a hotbed of hockey talent. “[While] he won city, provincial, and Atlantic championships, the larger hockey ecosystem in Canada didn’t know much of him at all.” Some considered his performance “meaningless because the caliber of the Nova Scotia league” was not up to snuff [70, 227, 37:58, Taking the Game…, p. 43-45].

Sidney was tenacious and made teams better than they should have been. His skill enabled “everyone around him to be better and do better and push harder. With his will to compete, [Sidney made] other players make themselves better” [Taking the Game…, p. 36]. His talent also drew the attention of opposing teams. Cole Harbour Red Wings coach Paul Gallagher would talk to referees before the games: “I told them that I understand they can’t call everything—if they did, we would have been on the power play all game. I just told them, ‘Look, if you can get the cheap and dangerous stuff, when they go after him with the slashes on the gloves [or] up the arms.’ [The refs] were actually really good about it. They understood that this was a special player. Not like he needed special treatment or protection or anything. Just that other teams shouldn’t be able to get away with things to drag him down to their level” [Most Valuable, p. 42].

Sidney led his Cole Harbour Red Wings to victory over the Moncton Subways at the Monctonian AAA Challenge hockey tournament on November 19, 2000, scoring one of the winning goals himself [262].

“It’s a small city and a small hockey community. Everybody knows everybody. I’ve known Sidney and Troy for years. Sidney soaks up the game like a sponge. It’s not just that he has an incredible work ethic. He wants to learn about things that can make him better. Some great players might be tough to coach or are even uncoachable but Sidney was always prepared to take in whatever a coach or an instructor at hockey school had to offer—a coach’s dream. He was just so positive about the game.” - Rick Bowness, former coach of the Phoenix Coyotes and a Halifax resident [Taking the Game…, p. 35]

Sidney’s year with the bantam team also enabled him to commit his most rebellious act yet: the Cole Harbour Red Wings bantam players decided to dye their hair red, which was not something Troy and Trina were pleased about. “Mine turned out maroon, something like that, because my hair’s darker,” Sidney said. “It didn’t turn out even the colour it was supposed to turn out. My parents knew I was doing it for a team thing. They understood that. It was important to me at the time. It was only for that reason. Once that season was over, the clippers came out and it was buzzed” [63].

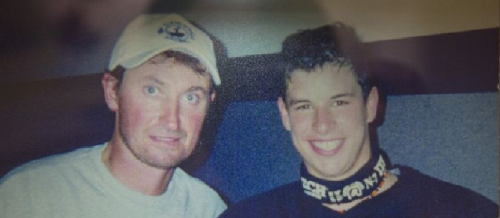

Sidney met Pat Brisson, his future agent (and a former teammate of Mario Lemieux in the 80s), at a tournament in Toronto [5, 66]. Brisson took Sidney on as an unofficial client of the International Management Group (IMG) and began inviting Sidney to hockey development opportunities, including a Los Angeles summer hockey camp. Brisson would often take 16- and 17-year-old players to this camp, but made an exception for a much-younger Sidney. Accompanied by his father, Sidney scrimmaged for two weeks against older players, including NHL stars Chris Chelios and Luc Robitaille [8, 12].

“He was 13 with his father, and he got on the ice, and I remember him doing a spoon, an amazing move around Chris Chelios, and Chris Chelios tried to turn around and slash him, like who’s this kid? What is he doing here? He just made me look like a fool.” - Max Talbot [168, 8:50]

“He was just a peanut. At 13, he was asking questions like an 18-year-old kid. It’s been going like that from the beginning. It keeps getting better and better because he wants to get better.” - Pat Brisson [5]

Sidney’s time spent playing with boys who were older and bigger than him led to more punishing physical abuse on the ice. Troy, concerned for his son’s health and physical fitness, started looking for personal trainers [The Rookie, p. 49]. Andy O’Brien fell into their lap while Sidney was at the elite hockey camp on Prince Edward Island [73, 229].

“He was a thirteen-year-old playing against sixteen-year-olds, and they wanted someone who could develop his mind and body so he could continue to compete against older players who were running him. They had identified their kid had a special talent and were willing to do whatever it took to develop it. And Sidney had a determination about wanting to develop as well. It just seemed to come very naturally to him.” - Andy O’Brien [The Rookie, p. 49]

O’Brien, a 22-year-old student of the University of Western Ontario’s kinesiology program, was a strength and conditioning coach and a guest presenter at the camp. He was somewhat of a radical thinker by hockey standards, much more interested in working specific muscle groups at high speed and striving for perfect form than building up muscle mass [229].

O’Brien was impressed by how Sidney used his entire body in a physical and aggressive manner. Sidney’s ability to be both a hard-working grinder and an unbelievably skilled player amazed O’Brien, as did Sidney’s awareness of his faults as a player. A “lumbering” skater, Sidney knew he needed to work on his speed and skating. Sidney and O’Brien hit it off, and O’Brien became Sidney’s trainer [73, 229].

“We’d been hearing about a player there who was said to be the best 13-year-old in the world. But when I realized that this was the player they were talking about, I thought, ‘Good lord, this kid needs some work.’ He was lumbering around a bit out there.” - Andy O’Brien [229]

Under O’Brien’s analytical eye, Sidney would do nontraditional workouts, jumping, sprinting, somersaulting, and doing hurdles while O’Brien corrected his form and pointed out mechanical flaws in his movements. Sidney would wobble on a piece of plywood balanced on a length of pipe while O’Brien would “hit him with all the force [he] could to knock him off” or throw a medicine ball at him, all to make Sidney’s movements as mechanically efficient as possible [229].

At the time, O’Brien was based in P.E.I., and the Crosbys considered moving to the island to continue Sidney’s training. O’Brien was just finishing college and decided to expand his business to Halifax instead, which meant the family could stay in Cole Harbour [The Rookie, p. 49]. Sidney and O’Brien started training that summer, working four hours a day and then increasing to six, spread over three sessions a day. “Speed work and lower body and then upper body workouts were punctuated by meal breaks to refuel” [The Rookie, p. 50]. Trina would drop Sidney off at O’Brien’s Halifax home at 8 a.m. and pick him up around 2 p.m. after she was finished with work [The Rookie, p. 50, 73].

“...we would eat together and I would teach him all about physiology, the names of the muscles and the philosophy behind what we were doing.” - Andy O’Brien [73]

Sidney and O’Brien trained up and down Citadel Hill in Halifax. “The former military fortress and national historic site sits atop steep slopes and offers uneven footing and inspirational views of the Atlantic Ocean—Mother Nature’s treadmill” [The Rookie, p. 50].

“It was a great way to throw off his balance and make him aware of his environment. We did a lot of agility work there, a lot of stops and starts. He ran up the hill with a medicine ball, up and down and laterally. It was a big part of his training. We love that hill.” - Andy O’Brien [The Rookie, p. 50-51].

What O’Brien liked best about training with Sidney was that Sidney was effectively a blank slate; he hadn’t developed any bad habits, so O’Brien was able to teach him how to move his muscles in ways that wouldn’t harm him while he ran, jumped, and stabilized his body. Sidney was such a diligent worker that O’Brien was inspired by him, and they became good friends [The Rookie, p. 50-51].

“The moment I met him, I was impressed with his maturity. When he walked into a weight room at thirteen, he knew exactly what he was doing and what he was there for. He reminded me of a lawyer entering a courtroom. He was polished and focused and had this gift of vision. He was able to free himself from distractions. He had the greatest amount of maturity of anyone I’d ever worked with. It made me want to work with him.

“So many times you hear about a great young player and then you never hear about them again, but he was very unusual.” - Andy O’Brien [The Rookie, p. 49]

Also at age 13, Sidney was drafted by the Maritime Junior A Hockey League’s Truro Bearcats on June 16, 2001. He was the fifth pick in the second round, and it was unusual to take a player so young; “They don’t come along very often—this skilled, this young,” said Truro General Manager Steve Crowell. “He’s got the ability to play at our level. Obviously with his size, we’ll have to have lots of protection for him” [260].

Sidney insisted he would be able to play junior A hockey—“I’ve been adapting to each level I’ve gone to each year. It’s no different. It’s a bigger step, but I think I can do it.”—but his tone changed after he attended the training camp for Truro [260]. Though he said the camp was a good learning experience, he admitted “I just wanted to prove I could make the team and, after camp, make my decision. I thought I had a lot more learning to do and I needed to develop a little bit more. I don’t think I was ready for the physical part” [264]. Sidney decided to play midget hockey rather than skip from bantam to junior A.

In school, Sidney was facing mounting attention from his peers. He was a bit of a homebody (“Even when he was 14 and his friends started going out on Friday nights, he never did,” Trina said. “He stayed home and watched movies” [60]) and his classmates sometimes made it hard for him to fit in. Astral Drive Junior High School Principal Tim Schaus recalled a girl grabbing Sidney’s arms in the hallway before announcing, “I’m going to marry Sidney Crosby. He’s going to be a millionaire” [54].

“He was already a superstar then, in terms of our community, and we knew he was going to be a high achiever. But you would never know it. Sidney, basically, wanted to be just like the other guys. He did not really want all the attention.” - Andrea Rushton, teacher [54]

Sidney was approved to play midget AAA hockey (typically ages 15-17) as a bantam-aged 14-year-old with the Dartmouth Subways. Though he was considered small (5’8”, 165 lbs.) and was the youngest player on the team, he went on record saying that he was confident in his ability to play [12, Taking the Game…, p. 45].

Most of the other players were two or three years older than him, including Sidney’s friend Jeff Kielbratowski. Kielbratowski, age 16, would sometimes chauffeur seventh-grader Sidney to school. Kielbratowski wanted to make sure that Sidney was always included but never overwhelmed by the team [75].

“He was always younger and would be a listener and always watching what guys were doing. He always wanted to be involved in stuff. Even if he was younger, he still wanted to be a part of everything.

“In the end we wanted to look out for him. The fact that he was 13 and playing with 16- and 17-year-olds, you want the best for your teammates, but also since he was so much younger we wanted to take care of him.” - Jeff Kielbratowski [75]

In the Nova Scotia AAA Midget Hockey League Icebreaker Tournament, held to help teams evaluate their rosters and make final cuts before the beginning of the regular season, Sidney scored a hat trick to lead the Subways to victory, 5-1 over the Pictou County Weeks in the tournament’s final [264]. It was a sign of what was to come: Sidney absolutely demolished the league, racking up 193 points in 74 games [8, 22, 137]. He came within four points of the league’s single-season record. His fantastic vision and excellent hockey sense were garnering praise, and he was already considered a possible top pick for the 2005 NHL Entry Draft [12].

“He has that exceedingly rare skill, that only the great ones possess, of being able to control the pace and tempo of the game whenever he is on the ice. I would liken him to a chess grandmaster in that he’s always plotting things six or seven moves ahead.

“He knows where every piece is on the board and he can envision possibilities within a play that other players could never possibly see. He’s just so imaginative out there; he’s like a hockey savant.” - Kyle Woodlief, Red Line Report publisher and chief scout [12]

The Dartmouth Subways were not a deep team; aside from Sidney, they only had a few players who might make it to major junior hockey. That didn’t stop Sidney from taking the team by the reins and leading it to provincial and regional championships [Most Valuable, p. 46]. He was the first to practice and the last to leave the ice, and before practice even began he’d work on skills in the hallway of the Dartmouth Sportsplex by himself [The Story of…, p. 11]. When he faced his childhood friend Mike Chiasson, who still played for Cole Harbour, Sidney pulled no punches and scored a hat trick on Chiasson in the third period [379].

“I’ve never met a person or a player as driven as him. He just wants to be the best in everything. To talk about Sidney Crosby fills your heart. I think he was made to play hockey. He has an innate ability that can’t be taught. He’s a hockey artist. He can do things others can only dream of.” - Brad Crossley, Dartmouth Subways coach [37]

The Dartmouth Subways played in the Mac's Midget AAA World Invitational Tournament in Calgary over Christmas and New Year’s. The Subways had a rough showing but Sidney still stood out, making it onto the tournament’s all-star team and catching the attention of Shattuck-St. Mary’s coach Tom Ward, whose team won the tournament for the third straight year [76, 272].

Though Sidney had elected to stay in midget hockey instead of advancing to junior A, he did play with the Truro Bearcats three times over the course of the 2001-2002 season: in the initial exhibition game in Truro, and then at two away games—one held in Dartmouth and one held in Halifax [340]. In those games 14-year-old Sidney suited up against 19- and 20-year-olds as an affiliate player [33, 34, 261, Most Valuable, p. 46]. Steve Crowell, GM and coach of the Bearcats, said Sidney was “beyond his years,” commenting that talking to him was like talking to a 25-year-old with Gretzky-like hockey skill [340].

The Truro Bearcats wanted to dress Sidney—in his #9 jersey—for their showing in the Fred Page Cup, but were unable to because the Dartmouth Subways kept winning, and winning, and winning, diving deeper into the AAA midget playoffs [340].

“[Sidney] set the standard for work and intensity. He didn’t need to be loud, but other guys could see how he went about things in the dressing room and on the ice. He never did things halfway. His commitment was total. It’s a cliche to talk about a star making everyone on the ice a better player—usually it just means that a star creates scoring chances and some guys bank in some rebounds, or he opens up the ice for others with all the attention that other teams give him. But with Sidney it really was true. He made his teammates want to be better. He made them believe that they could be better. They saw what he was able to do—what he had done with himself with practice and work and imagination—and they wanted to get there too.” - Brad Crossley, Dartmouth Subways coach [Most Valuable, p. 47]

Sidney and his Subways would meet the Pictou County Weeks again in the Nova Scotia AAA Midget Hockey League final in March of 2002. He’d tallied 27 points against Cape Breton West and South Shore on his way there. It was the third year Dartmouth and Pictou County had met in the finals; somewhat of a local rivalry had developed over the years [257].

Pictou County was an aggressive team, but Sidney was used to brutal treatment on the ice. “I have to find a way to score,” he said. “I expect them to clutch and grab, talk to me on the ice. They’re going to try anything to get me off my game” [257].

“He’s played through slashes that would break any normal person’s arm. It was vicious. But he plays better after he’s hit. It drives him more. There have been and always will be naysayers. But he likes to prove people wrong.” - Brad Crossley, Dartmouth Subways coach [37]

Pictou County forced Sidney to battle through “ferocious” checking. Sidney scored 6 goals and 10 points to help the Subways win the best-of-five series. “That was a battle the whole way through,” said Sidney. “Coming out on top gave us a lot of confidence going into Atlantics. I don’t know if there are too many teams in Canada that hit and clutch and grab like them, so that really helped prepare us” [294].

The Subways were preparing for their biggest challenge yet: the 2002 Air Canada Cup, Canada's national under-18 ice hockey club championship, held that year in Bathurst, N.B. [257, 22].

The Air Canada Cup was Sidney’s “coming-out party,” as coach (and former junior teammate of Troy, and high school classmate of Trina) Brad Crossley put it [245]. En route to the tournament, Sidney had scored an astounding 217 points (106 goals, 111 assists) in 81 games [76, Most Valuable, p. 47]. The Subways went 61-17-5 that season, with Sidney earning the leading scorer and MVP awards in the Nova Scotia Midget League [245, 269]. His outrageous numbers earned him a feature on a segment of CBC’s Hockey Day in Canada [19].

“By the time I coached him, he was in charge of his own destiny. The media attention was astronomical. We had TV cameras at practice and great coverage in the papers. It was something we’d never seen before. And he was like a professional. He spoke better than most 25 year olds. He had an amazing amount of maturity.” - Brad Crossley, Dartmouth Subways coach [24]

The Air Canada Cup was no small feat for the Subways; Darren Cossar of Hockey Nova Scotia described their performance as a “breakthrough” for Nova Scotian hockey. The tournament was broadcast by TSN and had publicity throughout the country with Sidney and the Subways as the fan-favorite narrative. Sidney went from a regional story to national news [Most Valuable, p. 47].

“Being from a small town, when you go to those international tournaments, it’s not the same. [Nova Scotia] is kind of looked upon as a small place, and you don’t always have the matching equipment teams from bigger cities or bigger teams have.” - Sidney Crosby [The Rookie, p. 236]

“It’s tough, when you grow up in a small town. It’s hard because you’re doing well in a small town, but then you have to realize ‘Hey, it’s a small place.’” - Sidney Crosby [20, 1:32]

Nova Scotian hockey simply couldn’t keep up with larger programs from Ontario or the West. The best minor hockey programs in Ontario had resources that Haligonians could only dream of. It’s common for Atlantic players to feel “like they were held back by living and growing up in the Maritimes—that they just didn’t have the numbers. Not enough good players to push each other. Not enough teams to compete against.” In Sidney’s case, it also shielded him from the media scrutiny that came along with bigger, richer programs. This was his first step onto the national stage, and as a Maritimer, he was making a statement [137, Taking the Game…, p. 29-31].

“When we would go out of town for tournaments, we’d talk to players from other cities at our hotel and we were always amazed to hear how much ice time and practice time these other teams were getting. We were really lucky to get a third practice in a week every once and a while. Usually it was just two. These other kids had practices or games every day. Sometimes, they said, they were practicing in the morning and having a game later. Plus, they were skating through the summer. We were playing baseball or doing something else... I always wonder how much better Sidney might have been if he had been growing up somewhere with a great hockey program, lots of practice time and all that other stuff.” - Tim Spidel, pee-wee hockey teammate [Taking the Game…, p. 29-30]

At the Air Canada Cup, Sidney—bleached blond and wearing a puka shell necklace—played “against some of the best players in the country, most of them two or three years older than him” [13]. Sidney cemented himself as a prodigy at the tournament with his “jaw-dropping, beyond-his-years effort” [12, The Rookie, p. 12]. Teammates acknowledged that he “was dominating the game in a different way than other skilled players” [13].

“Going in, there was pressure from the media and from what I was hearing around me all year, but I just put it to the back of my mind and played. I suppose that bit of extra pressure probably made me play a little more desperate, but I think I thrived on it and ended up coming out pretty good. It was good to prove some people wrong because there were people out there thinking I could do it at the provincial level and Atlantic Canada level, but they were pretty anxious to see what I could do at the national level.” - Sidney Crosby [12]

He led the tournament in scoring with 11 goals and 13 assists, including the game-winning goal in the last 32 seconds of the semifinal against the first-place Red Deer Chiefs. With that goal, the Subways became the first Nova Scotian team to advance to the Air Canada Cup championship game. The team was ecstatic and “rejuvenated” according to Crossley. “I don’t think they can feel any pain right now,” he said after their win [279].

“We’re not even thinking about the silver. We want to win it all.”

- Sidney Crosby [279]

The Subways faced off against the Tisdale Trojans in the final. The Trojans came prepared for Sidney, matching him against tall, big Tyson Strachan. “For a 14-year-old, I can't believe his mental toughness and his physical toughness. Every team here keyed on him all week long,” said Tisdale Coach Darrell Mann [Most Valuable, p. 48]. Sidney was contained for most of the final, only managing a single goal while Myles Zimmer—son of the Mayor of Tisdale—scored a hat trick in the first period [175]. The Subways lost the final 6-2 and settled for silver. Sidney had made his mark regardless. Tisdale Captain Michael Olson told Sidney during the post-game handshake, “You’re a hell of a hockey player and I’ll probably be watching you someday on TV” [Most Valuable, p. 48].

“They definitely caught us by surprise. We were a little nervous at the start and we didn’t get our feet moving. We might have been a little bit tentative playing in front of a national television audience, but we can’t use that as an excuse. They beat us and they’re a great team.” - Sidney Crosby [Most Valuable, p. 48]

Despite the loss, Sidney stole the show and won the MVP award as the youngest player in the tournament after scoring 24 points in 7 games [12, 51, 269]. He was the youngest player to ever do so [22]. Several of his teammates grabbed tournament signs and banners from around the rink after the Air Canada Cup ended—for some, this was the end of their hockey career [Most Valuable, p. 49].

For Sidney, it was just the beginning.

“I saw a different level of drive and ambition at the national championship [Dartmouth’s loss to Tisdale]. He just felt it was his right to make things happen. Coming from a small town and being so talented, he wanted to prove he wasn’t just a little guy from Nova Scotia. That was really the last year of Sidney truly being a kid.” - Brad Crossley, Dartmouth Subways coach [The Rookie, p. 27]

“I was trying to antagonize him the whole game. I remember one time I even asked him, ‘Who do you think you are, Wayne Gretzky or something?’

“Of course, four months later, Wayne Gretzky actually said that he [Crosby] was the next Wayne Gretzky. That was a kick in the face.” - Brett Parker, Tisdale forward [13]

Four months later, Sidney was attending a summer IMG prospects camp in Los Angeles [19]. It was there that he met Stan Butler, the head coach of Team Canada at the two previous World Junior tournaments [Most Valuable, p. 63]. Butler, who ran the camp, was impressed by Sidney’s skill.

“It is the vision thing that’s like Gretzky’s. Maybe more than just seeing where players are at any time on the ice, but a sense of where they are going, what they’re going to do and where the puck is going. It’s awareness-vision, instincts and feel all rolled together. You think, ‘Oh yeah, he guessed right that time.’ But then you realize that he’s not guessing because he’s right practically all the time.” - Stan Butler, coach for IMG summer camp [Taking the Game…, p. 78]

Butler knew what he was talking about; Wayne Gretzky was at the camp too [48, 20].

It was rare for a 14-year-old to be at the IMG prospects camp, but Sidney’s new stardom from the Air Canada Cup had made him a hot commodity across North America; the Antigonish Bulldogs junior A hockey team had gambled their first-round pick on him in May, hoping a new Canadian Hockey League rule prohibiting branch-to-branch transfers for underage midget players would keep Sidney local. There had been a history of junior A teams in Ontario and Saskatchewan poaching players from Maritime teams, and with the new rule Sidney had three options: prep school, continuing in AAA midget hockey in Nova Scotia, or progressing to junior A hockey in Nova Scotia. Antigonish Bulldogs GM Danny Berry had discussed his draft plans with Troy Crosby: “We met for an extended period of time and talked about Sidney’s education, his moving away from home, his age, things like that. He certainly respected our interest” [271].

Respect was all the Bulldogs were going to get. Junior A wouldn’t have been enough of a challenge for Sidney [Most Valuable, p. 57].

Playing with Gretzky, however, was.

IMG had staged this development camp for several seasons, using it as an incentive for elite clients in their teens and early 20s. Sidney, still 14, was the youngest client ever invited and drew Gretzky’s attention [Taking the Game…, p. 78]. When Gretzky took to the ice, Sidney “cheated his way down the bench” to make sure he’d be able to get a chance to skate with the man; unbeknownst to him, Gretzky was equally interested in getting on the ice with Sidney [20, 3:21].

“The one youngster who caught my eye the most was a kid out there who was only 14 at the time. Honestly I was so impressed by it that the next day I went back and I actually got on the ice to play with him.” - Wayne Gretzky [20, 2:40]

“He has everything. He’s the real deal and he will surprise a lot of people at the World Junior. We need more guys like him to come along. People say Canadians don’t have enough finesse, but he sure does... He will get more and more pressure as he goes along, but he has a love for the game. He says the right things. He’s a good kid. Most importantly at his age, he has good guidance from his parents.” - Wayne Gretzky [48]

Sidney was perhaps overly modest when asked about his shifts with Gretzky, telling reporters “It’s not too hard to play with him. All you have to do is keep your stick on the ice” [182]. Gretzky, meanwhile, had nothing but praise to heap on Sidney. He told a writer from The Arizona Republic that Sidney was “the only player he had ever seen who had a shot at breaking his own numerous NHL scoring records” [The Rookie, p. 2]. Gretzky believed Sidney was the best player to come along since Mario Lemieux, with the ability to see the game the same way Gretzky had at 14. Gretzky highlighted Sidney’s “incredible” skills and love of the game. It was apparent to him after only a day that Sidney was willing to do whatever it took to be better [Most Valuable, p. 64]. “From everything that I’ve seen,” he said, “Sidney can handle almost anything that comes along” [Taking the Game…, p. 79].

It was a busy summer for Sidney; between drafts and hockey camps, he found the time to join the National Under-20 World Juniors evaluation camp in Halifax. Though he was too young to play (he turned 15 three days before the start of the camp), Stan Butler from the IMG camp put in a good word with Marc Habschied, the newly-named coach of the Canadian team, so Sidney could spend 10 days with the players [48]. It was an unusual request but not unprecedented, and Butler assured Habschied that Sidney would crack the team within a few years [Most Valuable, p. 64].

At the evaluation camp, Sidney fetched water, moved tables, helped get food, carried hockey sticks, and passed out towels to the players. As payment, he was able to participate in team activities and even sleep in the team dorm. At one point, Pierre-Marc Bouchard had Sidney buy a fan for Bouchard’s hot dorm room [48, 131]. Though Sidney was able to ingratiate himself with the 40 players in attendance, he couldn’t skate in practices or scrimmages [Most Valuable, p. 64]. Of course, that didn’t mean they could keep him away from the ice entirely.

“We heard all about how good he was going to be. He didn’t skate with us, but sometimes when we’d be coming back for our afternoon practice, he would have gone on the ice during our lunch break.You could tell he had something special happening. He wasn’t a great big guy, and he had a baby face, I guess. But when we saw him just staying, playing around, well, we all know what it’s like. It was easy to tell that he had some real amazing skill. And then when he came off the ice, you could tell he was in amazing condition, just for a 14- or 15-year old, he was in shape like a pro.” - Jason Spezza, second overall pick in the 2001 NHL Entry Draft [Taking the Game…, p. 54]

Sidney got along with everybody, according to camp attendee Jason Spezza, and was good to have a laugh with. Spezza had a unique understanding of the problems Sidney faced; after being drafted by the Ottawa Senators in 2001, Spezza had been ridiculed by Senators coach Jacques Martin as being unready for the NHL at 19 [Most Valuable, p. 65].

“I told him that there are going to be a lot of things said and written about you and you’re going to get pulled in a whole bunch of directions. And I told him that no matter what goes on, have fun. Don’t forget that it’s supposed to be fun.” - Jason Spezza [Most Valuable, p. 65]

Though Sidney was younger than every other player, the players treated him like another teammate. Even so, “[he] wasn’t like most other kids his age.” Sidney really watched every little thing that went on at camp, in awe of the skill level of the players [272, Most Valuable, p. 65-66, Taking the Game…, p. 55]. “I’m just trying to absorb a lot,” he said. “They’re all good guys. You can tell they’re focused and they want to go somewhere, and they really want to represent their country” [272].

By the end of the month, however, Sidney would leave Canada. He had made his decision months before, having carefully weighed his options for even longer [76]. Canada wasn’t enough for him anymore.

Sidney was southbound, for the United States of America.