IV. SHATTUCK

The cradle of the Maritimes had turned into a microscope over the years; the praise from Wayne Gretzky catapulted Sidney to a level of more intense media attention and scrutiny than he had ever received.

“It’s one thing to be talented enough to earn a legend’s respect. It's another thing to be burdened by that much expectation and hype. If he doesn’t make it, it’s because he has been saddled with all this baggage.” - Gare Joyce, hockey columnist [Taking the Game…, p. 3]

Off the ice, strangers began driving by the Crosby house. Some knocked on the door and asked for Sidney by name. The family no longer went out to restaurants or theaters [60]. At the rink, “Men in the stands, frustrated at the way Crosby overshadowed their sons, would yell about breaking his neck, how he was going to get killed; come game time, Sidney found himself slashed, punched, hammered from behind” [8]. Sidney’s grandmothers, Linda Crosby and Catherine Forbes, “said they could barely watch him play, and had to cover their eyes with their sweaters, because they were always afraid he would get hurt” [The Rookie, p. 96].

“The last couple of years have been pretty hard on him, on the ice as well as off the ice. As a parent, you try to protect him from the verbal comments, but it’s hard to.” - Troy Crosby [283]

Sidney’s family did their best to keep life normal, but they found themselves in an increasingly impossible position. Troy Crosby had to style himself as the guardian for the family. Gare Joyce, a hockey writer, claimed that someone “only needed to talk to Troy Crosby for a few minutes to come away with a sense of his fierce protectiveness for his son.” It was a protectiveness so strong that Joyce “had never met any [other parent] who surpassed [Troy’s] intensity” [Most Valuable, p. 58-59].

“It wasn’t healthy for him to play here, physically or emotionally. He was taking a beating on the ice. Grown men and women were yelling at him, wanting to see him harmed. They cheered dirty hits. If he’d come back the following year, he would have been killed.” - Troy Crosby [49]

Troy was hypersensitive about Sidney’s wellbeing, and when he spoke to a reporter after Sidney’s groundbreaking performance at the Air Canada Cup, he revealed that the environment in Halifax was becoming toxic for Sidney. “[Sidney] gets more support when he goes away than he does here at home,” said Troy. “He doesn’t say much about the crap that goes on around him, but I know he hears it. There’s a lot of good people here, but there’s a lot of animosity” [Most Valuable, p. 58-59]. Ultimately, Troy and Trina believed that their son was in too much danger to continue playing locally [49, 72].

“I hated when people would hit him because he was so much smaller. When we were growing up, I was very protective of him; he was my older brother, no one messes with him—they have to mess with me kind of thing... I guess I was in the stands, and I was along the boards, and I would yell at the other players. I was probably four or five, yelling at them, telling them to stop hitting him.” - Taylor Crosby [74]

“They [Troy and Trina] heard a lot more of it. For me, I was always able to reason that it’s hockey. As personal as it gets, it’s still hockey. If I realize that, it doesn’t bother me so much. If someone says the same thing in a school or real-life atmosphere, you take it a different way. But in a hockey rink, the emotion catches people, even adults. So you have to reason it out and be the better person.” - Sidney Crosby [The Rookie, p. 189]

Midget hockey was offering diminishing returns—for many of Sidney’s Dartmouth teammates, the previous season had been their last eligible year for minor hockey, meaning the team lacked the depth for another serious attempt at the Air Canada Cup [Most Valuable, p. 57]. Between the weak team and the abuse Sidney was facing, it was time to cast a wider net. At 15 he was ready to compete in major junior hockey, but the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League, who owned his territorial rights, was unwilling to relax their age restrictions [Taking the Game…, p. 50].

Age wasn’t the only reason the Q turned Sidney away. Players had played up in major junior hockey before; the Ontario League (OHL) had allowed Jason Spezza to play for his hometown team the Brampton Battalion at age 15, and the Halifax Mooseheads likewise petitioned for Sidney to get a hometown exemption [12, 77]. The QMJHL was not so eager to grant their request, as the Mooseheads—unlike the Halifax minor league teams—were one of the stronger and richer programs [Taking the Game…, p. 50].

Though some QMJHL executives voiced concerns over whether Sidney was physically and emotionally mature enough to hack it in major junior, their real motivation was fueled by self-interest; rival teams in the Q weren’t about to bolster the Mooseheads’ roster with a player of Sidney’s caliber, and they were willing to sacrifice the inevitable boosts in marketing and attendance that would have followed Sidney into the league, even if he had played for the Sherbrooke Castors or Moncton Wildcats, who owned the first and second draft picks in 2002 [Taking the Game…, p. 50, Most Valuable, p. 57]

Sidney was left with a few alternatives, but “[the] closer to home the options were, the worse they became. The Canadian hockey establishment really didn't offer him a place to land for the coming season” [Most Valuable, p. 61]. The Maritime Junior A Hockey League—which included the Truro Bearcats Sidney had played three games for—was much weaker than its sister leagues in Central and Western Canada. Sidney had been contacted by dozens of Provincial A programs across the country (most notably the Notre Dame Hounds in Saskatchewan and the Georgetown Raiders in Ontario), but there would have been institutional resistance kicked up by the Antigonish Bulldogs in Nova Scotia, who had used their first-round pick in the Junior A draft on Sidney. With the new CHL rule prohibiting branch-to-branch transfers, officials likely would have blocked Sidney from moving to another province to play [76, Taking the Game…, p. 51].

They could not, however, block Sidney from moving to another country to play.

Enter Shattuck-St. Mary’s, a coeducational Episcopal-affiliated boarding school in Faribault, Minnesota [25]. 2000 miles away from home, Shattuck could offer Sidney the opportunity to play against “teams the caliber of junior A hockey—effectively the level between midget and major junior,” and the opportunity for sanctuary from the bullying he faced [8,12].

Shattuck was just emerging as a hockey powerhouse in 2002 and was well-known only to hockey inner circles. Sidney would put Shattuck on the map for the media over the next year. J.P. Parise, who had played for the Minnesota North Stars and the New York Islanders in the 60s and 70s, headed Shattuck’s hockey program and had shepherded several of the school’s bantam players to NCAA Division I schools and NHL drafts. His son Zach, along with several Shattuck players, was “credited with saving USA hockey from budget cuts with its first gold medal in the U18 2002 championship” [Most Valuable, p. 67-68].

If Quebec wouldn’t have Sidney, Minnesota would gladly take him.

Shattuck and Sidney had been on each other’s radars for over a year—in December 2001, Parise and Shattuck coach Tom Ward had seen Sidney play with the Dartmouth Subways at the Mac’s Midget AAA Tournament in Calgary [Most Valuable, p. 69, 76]. Sidney had even been coached by Ward in the All-Star team at the tournament. “That week,” Ward said, “Troy [Crosby] and a couple fathers from our school met, and we got the information that [Sidney] would be interested in looking at our school for the next little part of his adventure” [121].

Shattuck was known in Halifax; Brent MacLellan, a major junior prospect who had recently moved to Halifax from Toronto, had elected to go to Shattuck instead of playing locally. He enthusiastically recommended Shattuck, and Parise also pitched the school to the Crosby family and Pat Brisson in the spring of 2002 [Most Valuable, p. 69]. Brisson—who had established himself as the “Quebec league contemporary of Troy Crosby” insofar as protecting Sidney went—and J.P. Barry—one of the most influential agents in hockey—endorsed Shattuck, though they weren’t officially representing Sidney at the time. They called themselves his “advisors,” which was a necessary professional distance if Sidney eventually decided to play NCAA hockey [Taking the Game…, p. 52].

Shattuck wasn’t Sidney’s only option when it came to boarding schools; Upper Canada College, “the Toronto school for the privileged elite,” had received some consideration, but UCC’s hockey program paled in comparison to Shattuck’s, which was drawing in the best players from Minnesota and Canada. Many Canadians, especially those from the West, were attending Shattuck so they could test the waters of NCAA hockey [Taking the Game…, p. 51].

On June 15, Sidney attended the 2002 QMJHL Draft as a guest of Richard Paquette, another advisor from IMG. He watched the prospect luncheon with visible anticipation; “It was great seeing those guys go up there,” he said. “Hopefully, I’ll be there next year.” He told the media that he hadn’t yet decided where he was going to play the following season, and was at the draft to “meet some people and find out what it’s all about” [286].

That was a lie. The very next day, the Crosbys announced Sidney would attend Shattuck [76]. “I think it will be a good environment for me,” Sidney said. “People go there for education and sports. Everything is pretty focused. That’s the way I want to be” [269].

Though he was excited to compete against older players and showcase his talents to some major U.S. colleges, as Shattuck largely competed against U.S. junior A teams and Division 3 college teams, the decision was overlaid with sadness [269]. Troy had, up until this point, never missed one of Sidney’s hockey games [65]. Taylor was only 6 years old and was “devastated” by Sidney leaving [8, Most Valuable, p. 77].

“I didn’t understand why he had to leave. I think I’m really lucky because some people don’t get along with their brothers. He was actually really excited to have a sister. We’ve always been close—even when we lived far apart.” - Taylor Crosby [3]

“There comes a time when you’ve gotta do what’s right for him,” said Troy, and both of Sidney’s parents told the media it would have been “selfish” to make him stay in the Maritimes [283, 228, 4:40]. “It was very difficult. I cried," said Trina. “It was a wonderful opportunity for him to grow as a hockey player, and to mature. That’s the only thing that saw me through” [283].

“...I walked into his bedroom one day and his suitcase was there like it had been, and it just struck me at that moment, and I thought, ‘This is the way I’m going to see my son for the rest of my life.’” - Trina Crosby [228, 5:02]

“It was unbelievably tough. My heart was broken for a couple of weeks after he left.”

- Troy Crosby [65]

The Crosbys would miss each other. It was still the right decision—things were becoming very difficult for Troy and Trina at the arenas. People made demands of them, said horrible things to them, and another season would have been too much for the family. “I remember Trina just being so relieved that it was over and done with,” said Ed Spidel, the father of one of Sidney’s childhood teammates [Taking the Game…, p. 53].

“He needed an environment where he could just be Sidney. It didn’t come easily. Sidney had just turned 15, and I’ll tell you it wasn’t easy to do. But that’s how strongly we felt that he had to go. He needed it.” - Trina Crosby [49]

“You just feel like you’re a million miles away,” said Sidney [374]. It wasn’t easy, but he was willing to go the distance to follow his dream. “Leaving home was a tough decision, but I think it’s one that, when I’m 25, I’ll look back and be confident with the decision and have no regrets,” he said. “I’m very close to my parents and my other relatives, and I’ve a six-year-old sister I love, but it was time to go” [283].

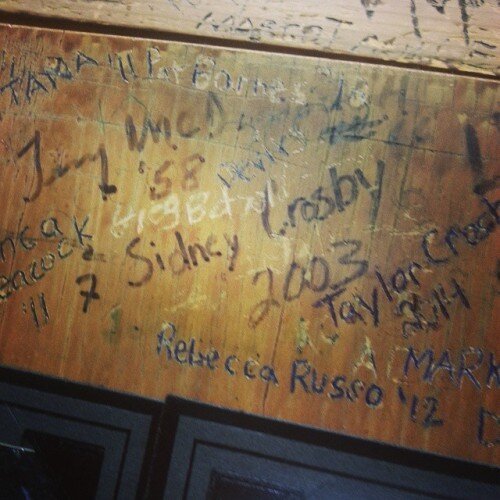

Sidney left for Faribault on August 30, 2002 [272]. It made waves and would prompt more players from the top midget ranks and Provincial A to follow [Taking the Game…, p. 53]. Down at Shattuck, the players were excited for “The Next One” to arrive. “It was a little bit of a mythical rumor,” said Kevin Deeth, a defenseman on the team. “Why the hell would a kid like that come to a place like this?” [121].

Shattuck was “to high school hockey what Harvard is to law school,” and Sidney was a straight-A student of hockey [19]. Shattuck—like Harvard—came with a price tag: around $30,000 at the time. Thankfully Shattuck did offer need-based financial aid, and the Crosby family’s income qualified Sidney for full assistance [29, 269].

“Sidney had a sense of what he was going to do. He told me, ‘Don’t worry. I’m going to pay every cent of that back.’ And he did pay the school back. In spades.” - Tom Ward, Shattuck Sabres coach [29]

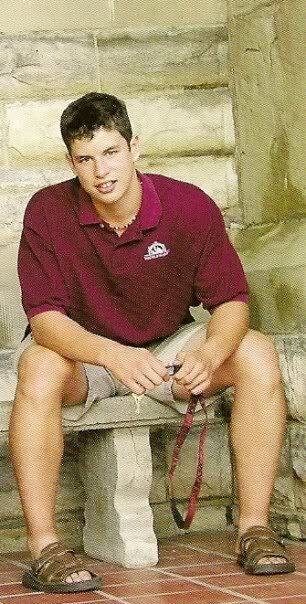

Sidney arrived at Shattuck as “a little boy, just a flat out young kid in a bunch of different ways,” his coach Tom Ward recalled. He was polite, referring to everyone as “sir” and “ma’am” [26]. The students and faculty liked him; he was down-to-earth and humble [2]. Deb Stafford, a teacher at Shattuck and mother of Sidney’s Shattuck teammate Drew, said Sidney was courteous and attentive. “He fit right in. He didn’t put on any airs. He was probably more of a B range [student]. He was a good student, but I wouldn’t say he was Mr. Brainiac either” [121].

Adjusting, as Sidney found out, was difficult. “It has been lonely,” he admitted. “At the start it was really hard, but once I started playing hockey every day and the guys were really good to me, it got easier” [Taking the Game…, p. 56]. Shattuck immersed Sidney in hockey; he was able to skate daily, something he’d never been able to do up in Canada [26]. He moved into the players’ dorm and “had his every waking moment scheduled by the coaching staff. Other kids might have balked. Sidney said he loved it” [Taking the Game…, p. 57].

“It’s just the entire environment. Everything’s hockey. Weekends or nights when you don’t have a game or you don’t have practice and your homework is done, you can just go over to the rink and play pickup hockey—basically pond hockey—for hours. That’s the special thing about that school and the environment. You just go out and play with your classmates and teammates who are all these good hockey players—you just get better without even realizing it. I can’t imagine a much better place to send your kid if he’s serious about being a hockey player.” - Jack Johnson [57]

As a parting gift, Sidney’s parents had given him a poster of the film character Rocky running up the stairs of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He loved the movies and hung the poster in his dorm room, room 303B in Whipple House, which he shared with teammate Ryan Duncan [30, 121].

“I loved that, and I identified with that image, those movies. They said it reminded them of how much I loved those movies. But I got a lot out of them. I loved how they portrayed hard work translating into winning.” - Sidney Crosby [The Rookie, p. 50]

(He also said, in an interview at 16, that he’d pick Sylvester Stallone to play him in a movie, because of the training and dedication of the Rocky character [170]).

Living semi-independently didn’t come entirely naturally to Sidney. His roommate, 17-year-old Ryan Duncan, admitted they “really didn’t know what [they] were doing,” and homesickness hit hard. They were the only two Canadians in the program. Duncan didn’t think he’d make it the full year at Shattuck. Sidney was “better that way” [30].

“We were lost—completely lost—when it came to cleaning. We didn’t know to hang towels up to dry after we used them. We just sort of threw them on the floor. So our room stank pretty bad. The worst came when my parents came to visit from Calgary and we tried to clean up. Under this pile of towels there was an infestation. It was pretty embarrassing.” - Ryan Duncan [30]

It was at Shattuck that Sidney met his future friend Jack Johnson. Both sophomores, Jack and Sidney were the only underclassmen to make the Shattuck prep hockey team (Jack had scored 100 points on Shattuck’s bantam team the year before; Sidney was Sidney) [16]. They were put on opposing teams during tryouts, which kindled a heated rivalry between them before they even knew each other’s names [28, 0:10]. The team had all heard hype about Sidney, but didn’t pay too much attention to it; it wasn’t until they saw Sidney in action that they realized he was truly that good [32].

Duncan had chatted with Sidney over the summer in preparation for their move-in. Duncan, who was two years older, was skeptical of Sidney’s skill: “My mindset was like, ‘How good could this kid be? I’m going to go down there. I’m going to outscore him. I’m going to go prove that I’m better than this kid’” [147].

His tune changed once tryouts began. Matt Smaby, a defenseman, said “You think this [15]-year-old hotshot may not be all he’s cracked up to be. I remember trying to hit him. That didn’t go well for me. Not only did I not hit him, I didn’t get a piece of him.” Other players would bounce off him as he spun and scored. Coach Ward claimed Sidney played like Peter Forsberg but with more skill [121]. “He was just heads-and-shoulders better than everybody,” said teammate Drew Stafford. “For a 15-year-old, he already had the body type... that power skating... His legs were enormous. He was built to be a hockey player, and it was pretty cool to see just how skilled he was” [Most Valuable, p. 74-75].

J.P. Parise himself admitted that Sidney was set apart from the other good players in Shattuck’s program, and his physical qualities were a significant asset [Taking the Game…, p. 56]. “You’d see him and think he was a normal kid,” said Deeth. “Then he’d turn around, and his legs and his ass were like the size of a fucking truck.” The physics teacher would use Sidney as part of class lessons, talking about how Sidney would lower his center of gravity to protect the puck [121].

Sidney’s grit and dedication were what truly separated him from the rest of the pack. He would practice endlessly, waking up early to get out on the rink and shoot pucks. Eventually his teammates started joining him. Although he was young, he was feisty. “He didn’t take no shit from anybody,” said Coach Ward [121]. From practicing at dawn to playing water basketball in the pool, Sidney always came to win.

“[Sidney] would not give an inch to you. There’s no playing for fun. He wanted to give it to you. He wanted to rub it in. His competitive juices carried over into everything, whether it was ping-pong or tennis or whatever. At the end of the day, Sidney wanted to be on top. Most of the time, he was.” - Ryan Duncan [121]

Sidney’s laser focus impressed his teammates. He was willing to sacrifice the “normal prep school shit,” as Deeth put it, in order to squeeze every last drop out of his time at Shattuck. He wasn’t interested in chasing girls or going out late—he’d go to bed early to make it out onto the ice at the first crack of sunlight. He’d turn down party invites and movie tickets so he could go play shinny. If there was a chance someone might get in trouble, he’d make himself scarce [11, 121, 245]. “He knew where he was going,” said Duncan, “and he wasn’t going to do anything to jeopardize his future. You could just tell how much of a professional he was at 15 years old. He was just so ahead of the game mentally” [147].

“He would work on little things, almost like little games, just playing with the puck on his stick. He would practice making it look like he had lost control of the puck—like it bounced up off his stick or dropped back in his skates—but really he was never out of control. He just wanted it to look like that so he could get a defenceman leaning.” - J.P Parise [Taking the Game…, p. 56]

Though he was competitive, he worked hard to become just another team player. When he overheard teammates on the bench talking smack about another player early on in the season, he said, “Hey, guys. Let’s keep everything positive. Don’t talk about your teammates that way” [121]. “Sidney made himself part of the program,” said Coach Ward. “He just wanted to fall in with everybody and he did” [Taking the Game…, p. 58].

“I think he liked the fact that he didn’t get special treatment. He had to try out like everyone else. And I think at some level he knew this was going to be the last time he was just Sid from Halifax, not Sidney Crosby, Hockey Star.” - Tom Ward, Shattuck Sabres coach [4]

Many of the Shattuck players had expected him to be cocky, but that wasn’t the case; Sidney was “super nice, super friendly, a little shy” [121]. It didn’t take long for him to endear himself to his teammates, and their hijinks occasionally spilled over into urban legend: some of them enjoy telling a story about Duncan and Sidney rappelling out of their dorm the night before tryouts to practice their timed mile—Duncan disputes the claim [121].

“[Sidney and Ryan Duncan] were like fucking cartoon characters to me. They were so different. Dunc was just a little shit—very social, super funny, big brother-esque—and picked on Sid despite being much smaller than him. Sid was such a good dude. Incredibly nice. Humble. Goofy.” - Kevin Deeth [121]

They played as a team and lived as a group of friends. During Easter break, Sidney and Duncan went to Smaby’s house and ended up at a nearby mall, cramming themselves onto the Easter Bunny’s lap for a picture. Sidney got behind the wheel of a car for the first time when his teammate Ken Rowe offered to give him a lesson, even though Sidney didn’t have a learner’s permit [121]. One day when Sidney was napping in Smaby’s room, the boys pranked him good:

“We all grew up watching ‘Mighty Ducks,’ so we decided to do the shaving cream and feather trick. We put the shaving cream in his hand and started to do the feather. I have never seen this work so well. We did it three or four times. He got [shaving cream] all over his face. Finally, the five or six of us in the room were cracking up so loud that he woke up because of all the noise.

“He took it in stride. He woke up smiling. He thought it was funny. It was nice for us older guys because that was the only time he wasn’t dominating us in practice. That was the one time we had the upper hand on Crosby.” - Kirk Golden [121]

Older students also enjoyed indoctrinating Sidney into the local ghost lore: the school’s old infirmary building from 1869 was popularly regarded as haunted. Shattuck’s ghost stories were “a big thing” at the school according to Sidney, and while he was living on campus, a TV show about haunted places in the United States mentioned Shattuck [302, 303].

Sidney had a slew of makeshift families at Shattuck; his team was one, and the Johnson family (who rented a home a block from the school so Jack wouldn’t have to board at Shattuck) was another [58]. J.P. Parise also kept a close eye on Sidney.

“Sidney used to come over, and Mrs. Johnson made I don’t know how many dozens of cookies for him. But then all of a sudden, he would be on his hands and knees playing mini-stick hockey with our 7-year-old Kenny. And next thing you know, Sidney and Jack are on the floor playing each other in mini-stick hockey.” - Jack Johnson Sr. [16]

“With J.P. and [wife] Donna, the whole Parise family was great to me. Every free weekend, I was away from home, so it was nice J.P. would bring me over to their house and I’d have a home-cooked meal and listen to J.P. tell stories. He just loved the game so much.” - Sidney Crosby [79]

At Shattuck, Sidney could be just one of the boys in a way he couldn’t in Canada. He was fairly anonymous most of the time—though the girls at the school did like him. He had never been on a date and confessed to assistant coach Eric Soltys he’d never kissed a girl, to which Soltys responded: “Buddy, this is great! Just be yourself” [121].

(He did end up going with a few girls to the local mall, and was impressed that he could walk around without being recognized [121].)

“That was probably the only year he got to just be a normal kid.” - Matthew Ford, Shattuck Sabres teammate [121]

Though Sidney enjoyed being the best, he liked being able to exist as a normal highschooler. “I think him being able to come to a place like Faribault, Minn., a little farm town, he could lose himself,” said Coach Ward. “Here he wasn’t the savior of hockey Canada. I think he appreciated that. He could just be one of the guys” [134, 121].

“I think he enjoyed his time away from the limelight in Canada, where he was the next great whoever. No one gave a spit who he was walking down the halls here. He’s not just a big, dumb jock, either. He’s worldly for being a young boy. He’s got his wits about him.” - Tom Ward, Shattuck Sabres coach [245]

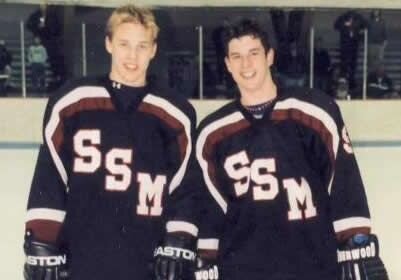

Though he didn’t stand out off the ice, he shone on it. Sidney donned #9 for the team—a number worn by several of Shattuck’s most elite players over the years—and amassed 72 goals and 162 points in 57 games as the team’s leading scorer [26, 4, 283]. According to Duncan, those numbers could have been even higher. Duncan said that in blowout games, Coach Ward would hardly play Sidney after the initial onslaught of goals ensured a Shattuck victory [29]. Sidney combined with Jack Johnson to become a dynamic duo, and the Shattuck-St. Mary Sabres began garnering local and national attention.

“Sidney was so dynamic. I’ve never seen a sophomore forward like Crosby—ever. And Jack as a sophomore defenseman in high school, I’ve never seen anyone like him either. Even at that time, they were exceptional. I think people went to Shattuck to watch those two play.” - Billy Powers, Michigan assistant coach [16]

“Usually, other teams didn’t know who we were as players—we were just a prep school from Minnesota. So it was funny. We’d get out there on the ice and go, ‘Boy, are these guys in for a surprise.’” - Jack Johnson [121]

Sidney’s relative anonymity wasn’t perfect; his teammates were bewildered when they rolled into Bozeman, Montana to play a game and a billboard had been erected outside the arena, proclaiming “Come see the next Wayne Gretzky play.” Magazines and news crews came in to interview Sidney, but his team still saw him as very “team-oriented.” Smaby said that playing in Calgary truly opened the team’s eyes as to what Sidney’s life looked like back home [2, 121].

“I was baffled that this humble 15-year-old that was part of helping us win, this kid on a high school team, had to carry that much weight on his shoulders.” - Matthew Ford, Shattuck Sabres teammate [121].

Back in Halifax, the Crosby family kept in touch best as they could. Trina would send Sidney cookies and Sidney was dutiful about calling home [121, 283]. Troy missed his son keenly. “It’s been especially tough not seeing him play now,” he said. “It kills me. I know when he plays. I look at the clock, and then I wait for him to call every Friday or Saturday night. Because of the two-hour time difference, I’m waiting up until midnight or 12:30 a.m., waiting for the phone to ring” [283].

Sidney ventured north to play Canadian hockey for a brief interlude that year. It was the only special consideration the Crosbys had asked of Shattuck: that Sidney be released to play in the Canada Winter Games [Taking the Game…, p. 58].

The 2003 Canada Winter Games were held in Bathurst-Campbellton, New Brunswick, from February 22 to March 8. Twenty-one sports were on the roster, involving 3,200 athletes and coaches [213]. The competition would be a good indicator of top prospects’ progress and could be a personal showcase if a player was able to set themselves apart from the rest [Taking the Game…, p. 58].

Sidney was the youngest player present at 15 years old. He was also named captain of the Nova Scotian team. “It sounds strange, but the truth is Sidney was a natural leader,” said Scott Vanderlinden, who had lost to Sidney and the Dartmouth Subways the past year in regional playoffs and went on to wear the A for Team Nova Scotia during the Winter Games. “Even though he was younger... Sidney just made you want to do whatever you could—if you had it in you, you had to leave it out on the ice. It was all through his example” [Taking the Game…, p. 59-60].

The Nova Scotian hockey team was incredibly weak. Not a single player had QMJHL experience—not that it would have mattered, as the Q was regarded as “the softest of the major junior loops.” Against teams like Alberta, whose players competed in the strong Western Hockey League, the Nova Scotians were sorely outmatched [Taking the Game…, p. 60-61].

Sidney took it personally. When Nova Scotia lost to Alberta 4-1 (with Sidney only tallying one assist), he started running the Albertans to try and spark life into his teammates. He dug in on the corners, throwing checks at bigger and older players, more than half of whom were used to playing against 18- and 19-year-olds. He earned himself a few roughing penalties for his troubles [261].

His teammates were spurred on by his gumption: “He just changes your mindset,” said Chad Anderson, a Team Nova Scotia teammate and former rival from local youth teams. “And it’s something when you’re on the bench or on the ice and you see him. Even if he’s having a bad game or having trouble with someone shadowing him, at some point he just makes up his mind, picks himself up and just makes things happen. He refuses to lose” [Taking the Game…, p. 60-61].

Against weaker teams like P.E.I. Sidney had a serious impact on the play, scoring four goals and two assists in a single game. “I love having the puck when there’s one minute left and scoring the game-winning goal,” he said. “I like to have this pressure.” Team Nova Scotia had a dominant 9-1 win over P.E.I. [261].

NHL scouts at the tournament were blown away by how Sidney took the reins of Team Nova Scotia. Even though Sidney wasn’t eligible for the NHL Draft until 2005, it didn’t stop the scouts from taking notice. Denis LeBlanc, a regional scout with the Columbus Blue Jackets, was impressed with Sidney’s completeness as a player. Sidney had the ability to skate, a strong hockey sense, good hands... everything it would take to make it in the big leagues. “Even if he’s not big, he’s so quick that I don’t think it’s going to be a problem for him in pro,” said LeBlanc [146, 261].

“The guy’s very smart. He’s going to be the number one draft pick, there’s no question about it. Everybody wants him.”

- Johnny Johnson, scout for the QMJHL's Montreal Rocket [146]

Sidney’s raw talent made him hypervisible on the team. It wasn’t wholly The Crosby Show, but it was very close. “I can’t think of one of the top players—not Gretzky, not Mario, not Orr—who was ever put in a situation like that,” said one scout. “Whenever they were in against the best... they weren’t ever with a team that was so far behind everyone else’s. If you look at Crosby’s Nova Scotia team, it would have been hard for any other player besides him to even make the Ontario team” [Taking the Game…, p. 61].

“If everyone in Canada didn’t know about Sidney yet, then at least everyone in hockey had heard about him.” - Chad Anderson, Team Nova Scotia teammate [Taking the Game…, p. 59]

Sidney had begun to settle into the scrutiny that accompanied these sort of events. “[The attention is] not a big worry when I come to things like this as much as it used to be,” he said. “I think I’m learning from my experiences. It’s the same game and if I play the same way things should be all right” [146, 261].

Though the Nova Scotian team finished sixth, it was a vast improvement on their ninth-place finish at the previous tournament. Sidney led the competition with 16 points in 5 games and took home the Roland Michener Award for outstanding athletic achievement and strong leadership skills. He had finally garnered some respect for Maritime hockey, as Darren Cossar of Hockey Nova Scotia explained: “It used to be that major junior was some far-off dream, something that wasn’t accessible [to kids from Nova Scotia].” Things were changing [22, 23, 27, 213, Taking the Game…, p. 62-63].

Sidney took it all in stride. “I’m just going to have fun playing hockey and at the end I guess I’ll have to figure out what I want to do with my life,” he said [Taking the Game…, p. 60].

The rest of his life could wait, because he was headed back to Shattuck.

Shattuck kept Sidney grounded. The team was tight-knit and academically focused. Every bus trip had at least one teacher on board to help tutor students. The players had to keep their dressing room as spotless as their grades—“The locker room is cleaner than any I’ve been in,” said Sidney [4]. Shattuck had, as Duncan put it, a particular way of doing things. “We all want it that way. We all go into Shattuck different and all come out the same” [Most Valuable, p. 76].

“We never got a class off or any break. One weekend we had an eight-hour bus ride, then we had to get off and play six games in three days. Getting back to Shattuck, we dropped our equipment off at the arena at 4 a.m. and had to be ready for class at 8.” - Jonathan Toews, former Shattuck student and player [4]

Shattuck provided Sidney with many experiences he would not have had access to otherwise; the hockey team took a ten-day trip to France to play three games, and Sidney “would have never dreamed of going somewhere like that if it wasn’t for hockey” [78]. When he returned from the trip, he brought with him a jar of sand from the D-Day beaches of Normandy as a gift for a friend back home in Nova Scotia [334].

The friendships Sidney made at Shattuck were deep, none more so than his relationship with Jack Johnson. Their little rivalry during tryouts spiraled into a strong friendship as they bonded over their youth and talent. The two fed off each other; they recognized each other’s talents and used each other to better their skills. Other boys on the team saw, as teammate Mike Mayhew put it, “Jack and Sidney go at it all the time” [16].

“We were idiot 15-year-olds, the only two 10th-graders on a team that was predominantly seniors. We had all of our classes together, too, so we just hit it off right away. We were inseparable. We know each other’s families really well, because in the summer, I’d go up and stay with him and hang out, work out and skate together.” - Jack Johnson [56]

Their closeness came as a surprise to some. On the surface, they didn’t seem to have much in common. With the media Sidney was quiet and chose his words carefully; Jack was straightforward and made his opinions known [16]. Perhaps opposites do attract, because their bond was visible to anyone who watched them play.

“You could tell by the way they interacted with each other and their mannerisms on the ice that they were not only special players but good friends.” - Mel Pearson, Michigan assistant coach [16]

Jack and Sidney stayed close off the ice as well. “We were able to relate to each other,” said Jack [364]. Their competitive nature was fierce, and they competed at anything, from “who could finish their lunch quicker [to] who could pick corners more accurately while shooting at a target on the tennis court” [26].

They were both recruited for the JV baseball team, as a team activity during the Spring was mandatory at Shattuck [57]. While playing against the Loyola Catholic School (in Jack’s very first game) Jack took issue with the Loyola pitcher, Zack Kolars [121]. According to Jack, Kolars was “kind of a big mouth” and chirping them from the mound [56]. The game was not going well for Shattuck; they were down 10-0, and Kolars had heard Sidney was a hockey hotshot.

“On the bus, our coach was telling us, ‘You guys are going to be playing the next Wayne Gretzky.’ We’re like, ‘We don’t give a shit, Andy. We don’t care about hockey.’ I kept calling him Stanley Crosby. I thought that was his name.” - Zack Kolars [121]

Still, things hadn’t boiled over... until Kolars threw a pitch that came very close to Sidney’s head. The next pitch hit him [16].

“I remember [Kolars] throwing at Sid. So I was like, all right, well the only way I know how to deal with this is the hockey mentality of charging the mound—he probably won’t do it again.” - Jack Johnson [121]

Sure enough, when Jack stepped up to the plate right after Sidney, he basically planted his elbow over the plate. “I put my feet right on home plate,” said Jack. “He’d either have to throw a ball or hit me. I didn’t know if I’d get up to bat again, so I was like, well, I’d better make this count.” Brian Cornelius, Loyola’s catcher, objected to the umpire, who said he’d call Jack out as soon as Kolars threw his pitch.

The pitch hit Jack.

Jack charged the mound.

“I remember thinking, What in the world is going on? This is B-squad baseball. Nothing gets this heated in a JV game.” - Andy Oberle, Loyola head coach [121]

Kolars was in disbelief that Jack was coming for him. Sidney, on the other hand, jumped off the bench to get involved. He grabbed the catcher—hockey instincts—to stop Cornelius from joining in. Much to the horror of the Loyola parents in attendance, Kolars got a punch to the gut and an elbow to the head. The teams’ benches scattered. The second baseman threw his glove at Jack. Chaos erupted.

The chaos had been planned, as it turned out.

It didn’t come out until years later that Jack had told nearly the entire hockey team before the game even started that he wanted to rush the mound that day. Many of Jack’s friends showed up, eager to see him do something stupid. “We were there to watch,” said Deeth. “Trust me, the only reason we were at a JV baseball game was because Jack said he was going to rush the mound” [121].

The stunt got both Sidney and Jack kicked off the team by Shattuck’s athletic director—it was the last competitive baseball game Sidney ever played in [26, 56, 121, 227, 40:04].

“I remember telling our guys on the bus after the game, ‘We’ll have to keep an eye on this. If they’re Shattuck hockey players, they might end up somewhere. That will be a really good story at some point.’” - Andy Oberle, Loyola head coach [121]

The baseball incident wasn’t the only time the two got into trouble; in their Modern European history class they would sit in the back and use their school-issued laptops to watch hockey highlights, unaware that their teacher (who was also their baseball coach) could see exactly what they were doing thanks to the reflection on a glass wall behind them [26].

For all their antics off the ice, Jack was a stalwart friend at the rink. As Mel Pearson (the Michigan assistant coach) recounted, “...the local team had assigned two kids to shadow Sidney and take Sidney off his game. He played through it and you could tell he was one of the best players. And that’s how you could tell Jack was one of his buddies, because every time there was a skirmish, Jack was right there to make sure he was helping Sidney out” [16].

Jack was a genuine protector for Sidney on the ice; he built up 91 penalty minutes in 21 games, and “his days as an enforcer on the ice began during his season playing with [Sidney]” [16].

“Prior to [the 2002-2003 season] I was one of the smaller guys on the team. I couldn’t really check the other guys, because they were usually bigger than I was. He was the first time I kept an eye on someone, and because we were such close friends I didn’t want anyone to give him a cheap shot or anything. I enjoyed doing it.” - Jack Johnson [16]

Sidney, even lacking the notoriety he had up in Canada, still brought enough attention upon himself that he needed a protector or two. He also developed his own ways of curtailing bad behavior from players and fans alike. One story about a woman (said to be Phil Kessel’s mother) yelling things at him stands out:

She was sitting in the corner of the rink, right behind the glass, so 15-year-old Sid could hear every word. Before a faceoff in the opponent’s zone, he scrapped the original plan to tap the draw back to Johnson on the blue line.

“I’ll take this,” Crosby said. Then he controlled the puck, skated in, scored, and circled over to the loud mom, putting a hand to his ear. The woman (he won’t say who) didn’t make a peep for the rest of the game [11].

The Shattuck Sabres played a commanding season with Sidney at the helm. “He was such a natural leader that nothing he did or said felt forced,” said teammate Brian Salcido [121]. Though the U.S.’s hockey culture was very different than Canada’s—rivalries between individual players can be much more intense in the U.S.—Sidney helped forge a real team [Taking the Game…, p. 58]. “He gets the point across that he’s competitive and he wants to win, and this is what you have to do,” said Duncan, “But in a subtle way. It’s like we’re all pulling at the same rope” [147].

He even roped them into a few fun new rituals, including one that apparently still persists at Whipple House. At the 2002 Salt Lake Olympics, the Canadian ice crew put a Canadian loonie at center ice. Canada won gold, and just over a year later, Sidney and Duncan taped loonies outside of their dorm room in an attempt to capture that same luck. According to Duncan, those two loonies are still taped up outside of room 303B [121].

“When we were getting ready for nationals, he found these little pills that you could put a hidden message inside. They unscrewed, and inside was a tiny scroll. He gave one to every teammate... He had everyone fill one out. He didn’t tell anyone what to write, but he made it known that we all knew what the goal was: winning nationals. So we wrote on our scrolls, rolled them up and put them in the pill thing. We kept them with us everywhere we went.” - Brian Salcido, Shattuck Sabres teammate [121]

That April, Sidney and the Sabres went on to win the USA Hockey 17-under Tier I Championship (the Midget AAA national title) in a 5-4 victory against Team Illinois. Sidney, still 15, scored 10 goals in 6 games and tallied 18 points, good enough to tie for the championship’s points leader award [16, 121, 22].

“I think he had that dream for himself, so he knew the work that he needed to put in. He wasn’t afraid of it. It wasn’t this weight that he was carrying around—he was just having fun, felt fortunate that he got to play this great game.” - Ryan Duncan, Shattuck Sabres teammate [147]

His hockey was speaking for itself yet again, and his year was up. His future was up in the air. Over the coming summer, he would turn 16 and be eligible to play major junior hockey in Canada. If he elected to play in the Q, he would be unable to ever play NCAA hockey.

College hockey had tried to woo Sidney over the course of the school year. J.P. Parise, on a visit to North Dakota to see his son, let Duncan and Sidney tag along. It was the first time Sidney had seen college hockey, and North Dakota was vying desperately for his attention. The games were “intense.” When the Sabres practiced at the University of Wisconsin’s rink on their way to Indiana for a game, the University also attempted to recruit Sidney, even going as far to put a jersey for him in the locker room [121].

“I don’t know if you'd call it pressure; it’s more anxiety, really. We just hope we do the right thing, and what’s best for Sidney and his future. It’s not a simple choice. Sidney is both a good student and a top prospect, so it’s a tougher decision.” - Troy Crosby [283]

Sidney was genuinely considering college as an option. The quality of the game was high and he thought he’d enjoy the campus lifestyle. There was one big hangup, though: going to college would have meant trying to finish two years of high school in one. Colleges wanted to fast-track him and make him the youngest player on their roster [121]. Sidney, too, didn’t want to languish in Faribault, outpacing the available quality of hockey while he got his diploma [Most Valuable, p. 76].

“I’m a decent student—a good one—but that would have been a really tough year,” Sidney said. “I liked Shattuck. I loved the dorms and everything to do with the school. And I want to go out there the first chance I get to visit some of my friends. But I didn’t really want to go through [doing two school years in one]. And if it was going to take two [more] years at Shattuck, then junior looks even better” [Taking the Game…, p. 87].

So Shattuck was out.

“It was my first experience away from Nova Scotia, and I had to catch up academically. I struggled with it at first. But I loved the atmosphere. You can have friendships wherever you play, but at Shattuck, you lived together, went to class together, traveled and played together. You get to know each other—everyone—a lot faster and a lot better. Leaving Shattuck was the hardest decision I’ve had to make.” - Sidney Crosby [4]

At the end of the school year, Sidney’s teammates threw him a mock press conference, setting up a desk in the hallway across from Smaby and Jake Hipp’s room [121]. It was a lot of fanfare for Sidney to announce his decision on where he’d play in the coming season, but it was deserved; Sidney was already starting to make money from hockey. At 15, he signed a relatively small 5-year apparel endorsement with Sherwood Hockey, maker of hockey sticks [84]. His name would be on their new Momentum stick [42].

“We were getting shipments of stuff for Sid. He was 15, and he was already a big deal. He always told me that he was OK with getting the attention. But the thing was, he didn’t want to get that kind of attention and to be getting stuff in front of other players. Here he is, at 15, telling me that he doesn’t want to be getting this kind of attention in front of other kids because he didn’t want them to feel bad.” - Pat Brisson [87]

He was becoming a bona-fide hockey star, and he’d take the media circus with him back to Canada... this time to Quebec.