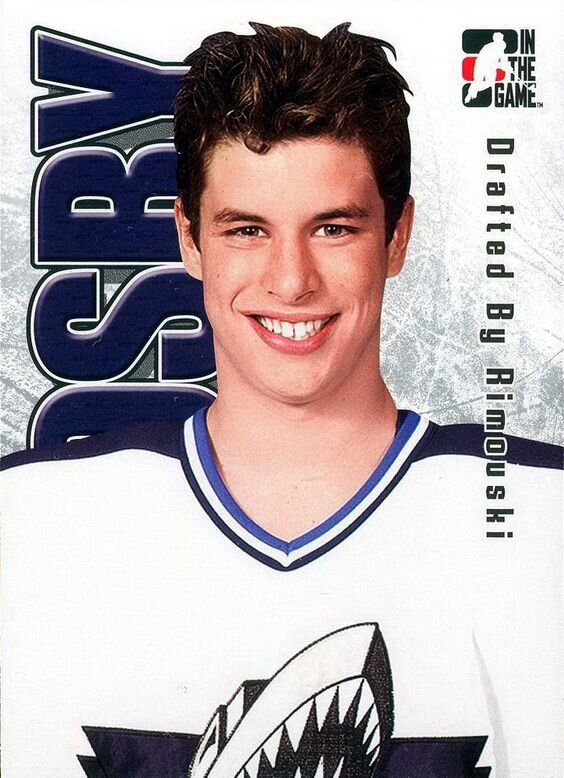

vi. rimouski i

Rimouski, a remote French-Canadian town, sits on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River.

It’s 300 kilometers northeast of Quebec City, ever-so-slightly on the cusp of the Eastern time zone. Night falls at 3:30 p.m. in November, and it can feel like the Maritimes when the wind gusts off of the river with the rising tide.

Originally a hub of trade and forestry during Canadian railway expansion, Rimouski had transformed into a town of Quebec government offices, oceanography... and hockey [313].

L’Océanic de Rimouski had fallen far since their 2000 Memorial Cup win—in the 2002-2003 season, the Océanic was the worst junior team in all of Canada. Océanic forward Eric Neilson struggled mightily to keep his place on the roster. He had gotten “off the tracks,” distracted by girls, parties, and late-night trouble. He’d been given a second chance, and then a third, but it finally came down to a meeting in a team office with the Océanic’s top brass [116].

“...they gave me a one-way bus ticket and said ‘You’re off the team. You’re not the player we thought you were. This is not what we wanted, not what we had in mind.’

It was like an epiphany. I had this flashback, working with my dad doing ventilation with heat pumps and duct work and everything, and had another flash of being a hockey player, going to the gym, being the first one there, sacrificing what you need to sacrifice to make it.

It was like a 180, I turned around, ripped the bus ticket up and threw it on the ground and said ‘Boys, give me one more chance.’” - Eric Neilson [116]

The team officials were unmoved, all except the Océanic’s assistant coach, Donald Dufresne. Dufresne told Neilson this was his last shot and Neilson finally put in the work to earn his team’s trust back. Still, the season ended with only 11 games in the “win” column. Things looked dire.

Then the Océanic officials summoned Neilson back to the office. The team was about to draft a kid from Nova Scotia, some sort of prodigy. Neilson had proven he could get his life back on the rails, and they wanted him to be the new kid’s roommate and mentor [116].

“I said, ‘Yeah, sure. Who is it?’, and that’s when they said ‘Sidney Crosby.’

And I was like, ‘Who? Who’s that?’” - Eric Neilson [116]

Neilson didn’t know much about Sidney, but he knew of him. He knew Sidney was an important prospect and had to be pretty good to wind up as the first-overall draft pick [147].

Then he met him.

“I meet this kid for the first time, and he’s just like a goofball. Like, he’s just got the big buck teeth and the bad hair. I’m looking at him and I’m like, ‘This is the kid that everybody’s got all the hype about?’ Like, he just didn’t have the look, you know what I mean?” - Eric Neilson [147]

To be fair, Sidney was also wary of his new roommate. Sidney had arrived in Rimouski a day earlier, on August 18, and tagged along to the bus station with his billet family, Christian Bouchard and Christine St. Ogne. Bouchard taught 7th and 8th grade history and geography, and his girlfriend St. Ogne taught 3rd grade. Sidney had met Bouchard when he was drafted, as his living situation was a key component in his choice to play for the Océanic. Originally, Bouchard was only to be Sidney’s tutor for his schooling, which would be done entirely by correspondence. Trina took a liking to Bouchard and requested the team place Sidney with Bouchard for his billet. Bouchard was happy to accommodate [116, 278, 295, 348, Taking the Game…, p. 133-134].

Off the bus came Neilson, with a mushroom haircut and more energy than anyone should have after a long bus ride. At first glance, Sidney thought Neilson would make a great roommate. Then, at their billet house on rue des Jésuites, Neilson told Sidney “Make sure you open my window tonight” [116, 321].

Old habits died hard. Neilson was already looking to break curfew on his first night back in Rimouski, and he wasn’t above assigning coverup duties to the rookie. They would be living in a two-bedroom apartment in Bouchard’s basement, sharing a living room and a bathroom [295]. Neilson waited at the billet to see if there would be a curfew call, then snuck out after instructing Sidney to open the window into Neilson’s bedroom so he could get back in.

Sidney went to his own bedroom and promptly fell asleep. He’d entirely forgotten Neilson’s instructions, and a few hours after midnight, he woke to loud bangs and crashes. Disoriented and unused to his new billet, he rolled over and dropped back off to sleep. The next morning, Sidney went to wake Neilson up for their first practice of the season. He opened Neilson’s bedroom door to the sight of a destroyed window and a very unhappy Neilson [116].

“He just rolls over, and he’s so pissed off at me. I think he just sighed and said, ‘What did I ask you?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I know. Sorry, I totally forgot. I fell asleep.’” - Sidney Crosby [116]

It was a rocky start, but Sidney would make up for it on the ice.

There had been some concern over how Sidney would adapt to major junior hockey. The schedule was jam-packed and more intense than Sidney had ever experienced. Moreover, the major junior lifestyle and media attention would be a far cry from the sheltered prep school life at Shattuck [313]. Even the style of hockey in Rimouski was a cause for worry; the Q was a defense-systems-heavy league when Sidney got to it. Pat Brisson, who had played in the Q many years prior, admitted that the old Q he’d experienced “was a lot more fun to watch and a lot more fun to play in” [66].

Naysayers were also skeptical of his ability to make it through major junior hockey to the NHL. He still wasn’t a very sizable player, and in the NHL, size often mattered. In defense of his height, Sidney would say if players of average builds like Paul Kariya, Steve Yzerman, and Wayne Gretzky could make it pro, so could he [228, 11:07].

“Every year it seems they want to see how I do at the next level. Everyone is questioned when they make a jump or step to the next level and I’m not any different. I just make sure I’m worrying about playing my game and not changing anything. I’m sure with hard work I’ll be fine. It’s up to me to prove I can play. I have no problem with that.” - Sidney Crosby [205]

The Océanic’s first preseason game in September was a showdown against their arch-rival, the Baie-Comeau Drakkar. The arena was sold out. Sidney was excited, saying “It should be a good atmosphere. I just kind of want the season to start. It’s kind of been a summer of anticipation. I want it to get going” [313, 278].

Neilson and some of the team’s veterans weren’t in the lineup for the first preseason game, so they sat back in the stands and watched as this 16-year-old from Nova Scotia tore up the ice.

“This kid goes out there and he just lights it up. He got four goals, four assists as a 16-year-old, first exhibition game in the Q, just a man playing with boys.”

- Eric Neilson [116]

Neilson, along with his teammates Mark Tobin, Erick Tremblay, and Danny Stewart, decided Sidney needed a new name. They didn’t care for the nicknames the media had given Sidney, and Sidney didn’t like them either. The Gretzky hype over the summer still buzzed in media narratives. People discussed his jersey number—finally his iconic 87—as being unusual, just like Gretzky’s. Mark Tobin, an Océanic left winger, briefly floated “Gretz” as a nickname. Sidney put a stop to it immediately: “I am not Gretz,” he told the media [19].

“He never wanted to be the next Wayne Gretzky or the next Mario Lemieux. He wants to be Sidney Crosby. He’s comfortable with who he is. He’s not just playing hockey. He’s playing to be the best he can be. He hates to lose. Hates it. He’s his own worst critic. He’s always trying to get better.” - Troy Crosby [37]

“I realize a lot of guys have been tagged with that ‘next great player’ thing. Some have gone on to be great players, some have fallen. I don’t want to be one of the guys who disappears. I remind myself of that every day.” - Sidney Crosby [19]

There were five minutes left in the game and Sidney had posted 8 points on the scoreboard: 4 goals and 4 assists. Though it wasn’t Darryl Sittler’s NHL record of 10 points in a game, it came pretty damn close, and that was good enough for the Océanic veterans [19, 116].

When the players wandered into the locker room, they swarmed Sidney with Hey, Darryl and Great game, Darryl! Sidney was baffled and wanted to know what was going on, but in the time-honored tradition of giving new guys a hard time, the veterans didn’t explain. The next day, they used white tape and a marker to correct Sidney’s name on all of his gear. His sticks, his sandals, his nameplate all now belonged to Darryl [116].

“He will be his own model. He will make his own name.” - Donald Dufresne, Rimouski Océanic Coach [22]

In the four preseason games Sidney played in, he notched 14 points. In his regular season debut in Rouyn-Noranda, he scored 3 goals in 7 minutes during the third period, lifting the Océanic to a 4-3 victory. That night, he had 25% of the team’s shots on goal. Many of the Océanic’s better players were at pro camps that early in the season, and Sidney had grown frustrated when his linemates kept flubbing on his set-ups for goals. He’d taken matters into his own hands [328]. In his first home game, a 7-6 win over Moncton, he scored a goal, the overtime winner, and netted 3 assists [221]. It was the beginning of a blazing September—he’d be named the QMJHL Offensive Player of the Week twice and then the Canadian Hockey League Player of the Week after scoring 10 goals and 8 assists during the month. After 18 games, he had racked up 37 points [22, Taking the Game…, p. 111].

“I didn’t expect to adjust so fast. I thought there was going to be a little bit more room for adjusting the first 10 or 15 games, but I seemed to be able to step right in there the first game and feel comfortable.” - Sidney Crosby [136]

It was a stunning performance. Donald Dufresne, now the Océanic’s head coach, told reporters that Sidney brought “skills and speed to the game that [he’d] never seen in a 16-year-old.” The Q was a league for 19-year-olds, not kids Sidney’s age [Most Valuable, p. 113].

Those who had known Sidney for longer were less surprised. “We expected him to be dominating in this league, probably the top two or three in scoring,” Pat Brisson admitted. “We thought there was going to be maybe a longer learning period. He actually came in, and the first night he scored three goals” [228, 8:30]. Sidney’s smooth skating, explosive speed, and bodily strength made him a force on the ice, and the points piled up. “It’s not like I didn’t think I could do it, because I set pretty high goals for myself,” said Sidney [313].

“I’m not satisfied by any means. I want to keep going. I want to be consistent. It’s good to be able to start off pretty good, but at the same time, it’s easy to go pointless in this league. It’s easy to make mistakes and for other teams to capitalize on them. So you can’t take things for granted at all, because it could catch up to you in a hurry.” - Sidney Crosby [297]

Sidney was slightly blasé about his talent—“Mostly it’s just read and react. It’s not brain surgery,” he said. “You see a guy and figure out what he’s going to do and try to angle him. It’s like anything, when you do it a lot, it becomes natural” [313]. His nonchalance didn’t stop him from being a target for other players. While playing against the Rouyn-Noranda Huskies on November 22, 2003, Sidney was dragged down to the ice in the dying minutes of the second period. The refs took no notice, and once the buzzer sounded, Sidney went over to complain.

As it turned out, refs don’t care for it when 16-year-olds criticize their work, and Sidney got slammed with a 10-minute misconduct in response. “He’s human too,” explained Océanic Assistant General Manager Doris Labonté. “Some nights you’re just not going to have it. At 16, we can understand that. Maybe your passes are off a little bit. Maybe a teammate doesn’t score when he has a chance. Maybe the goaltender is having a good night. It’s a long season. The games get tougher as the season goes on” [313].

The human aspect of major junior was another adjustment for Sidney. “It seems like every year almost, I’m starting over,” he said. “It’s really hard to be away from home, to make friendships and then have to leave” [124]. Sidney called home every night—he missed Taylor, who was 7 years old at the time—and Troy often made trips out to see as many games as he could [43, 45, Taking the Game…, p. 131]. As for school, he was tutored at his billet for 3 hours a day. His parents had made an agreement with the Océanic that the team would help provide Sidney with educational resources like tutors and a laptop. For all Troy’s efforts to get Sidney a robust education, it wasn’t a normal one; Sidney told reporters he didn’t have a girlfriend because he wasn’t a “regular high-school student” [43, 221, 365].

“It was actually harder going to Minnesota last year than coming here, where there’s a family atmosphere and a billet. Home is only eight hours away by car, so my parents can come to games and my little sister Taylor loves the team mascot.” - Sidney Crosby [335]

Away from the rink, Sidney lived in the bubble of his billet. Christian Bouchard said Sidney was very nice, very quiet, very polite... and a “funny guy.” Bouchard found Sidney to be a little sheltered for his age; apparently Sidney was shocked to learn that Bouchard and St. Ogne weren’t married, even though they were living together. “In the beginning,” said Bouchard, “it was ‘Oh, you’re not married, and you live in the same house?’” [295, 381].

Sidney’s habit of forming little superstitions held strong in his new environment. Bouchard would have to greet him a certain way in the mornings, and Sidney always took a small bagel with him to the rink, which Bouchard would place in the same spot on the counter every morning. Aside from his peculiarities and his supernatural ability to be good at all sports—Bouchard noted Sidney was good at both baseball and tennis, having witnessed Sidney take part in pickup games at the baseball field right next to the Océanic’s rink—he just enjoyed living as normal of a life as he could manage. “He’s a normal kid,” said Bouchard. “He goes on the Internet, chats with his friends, plays Nintendo, like a normal kid will do at his age” [31, 295, 348].

Sidney was normal until the food got brought out, though. Bouchard did most of the cooking in the household, as he had a background in the food service industry, and he was taken aback by the habits Sidney had around food [Taking the Game…, p. 133-134]. “Sidney has rituals,” Bouchard said, “like eating the same meals at the same time. And if they lost, that meal went out the window. He doesn’t eat any junk food and I have never seen anybody read food labels the way Sidney does. It’s amazing” [44]. Sidney was fastidious about reading food labels at the grocery store (he turned away food that was too sugary) and gave junk food a wide berth [295].

“Even me, if I went to a restaurant the day before a match or the day of a match, and if he won, the next time he would say: ‘Where did you go to eat before the match? Can you go back next week?’” - Christian Bouchard [348]

What Bouchard wasn’t surprised by was the quantity of food two QMJHL players needed. “It’s not that much work," he commented. “You need to have dinner for two, so you just make dinner for eight now” [295].

Neilson and Sidney had grown closer since their rocky start. Neilson was 19; Sidney was 16. “I consider Sidney to be my little brother and part of my family,” said Neilson [90]. He got a kick out of Sidney claiming to be a real salt-of-the-earth guy. According to Neilson, Sidney styled himself as a woodsy, outdoorsy type, saying he knew a lot about hunting and fishing. Neilson saw right through him. Though Sidney claimed to be a country boy, he was a hometown boy—Cole Harbour through and through [347].

“We talked about girls, and hockey, everything really, but at the end of the conversation that night right before we went to bed, he looked at me and said; ‘I’m going to be the best hockey player in the world.’

“I looked at him and said ‘OK, good luck man, I’m here to support you and help in any way.’” - Eric Neilson [90]

Neilson got a kick out of Sidney and his relentless pursuit of hockey greatness (which included putting “score and win” on the ceiling over his bed so it would be the first thing he saw in the morning. Neilson, in comparison, had a picture of Pamela Anderson above his own). Everything was a competition to be solved by rock-paper-scissors: who got which seat in the car, who got to use the shared bathroom first in the morning, who got to the rink earliest. Sidney would insist on being the first to practice and the first onto the ice, and then the first in line to do any drills. This wasn’t a welcome shake-up in protocol for the veterans on the team, but it was hard to argue when Sidney would do the drill perfectly. Sometimes other players would hide one of Sidney’s skates or another piece of equipment in an attempt to stymie his need to be first into the rink; Sidney didn’t take it well. Even in “fun” competitions, he had a need to win. Neilson and Sidney set up a basketball net in their basement apartment, and while they watched hockey highlights on TV they’d play best-of-seven games. If Neilson would win—that’s an if—Sidney would slam his bedroom door and refuse to talk to Neilson for the rest of the night [147, 347].

Neilson put up with it. It got him a car, after all.

A local Mazda dealership had given Sidney a sponsored car. The only problem was that Sidney didn’t have his driver’s license yet. Thus, Neilson became his personal chauffeur. The dealership put “87 Crosby” on the passenger side door. On the driver’s side was “29 Neilson.” Neilson tried to give Sidney a few driving lessons, but Neilson declared Sidney an “awful driver” and put an end to it. It didn’t help that the car was a stick shift. Sidney admitted he “almost ruined” the car [66, 78, 116].

Neilson was the one to actually ruin the car.

One night, Neilson was driving home a few drunk teammates (and girls) and picked a bad time to show off. He tried to drift around a corner and lost control of the vehicle, crashing it. Luckily none of the passengers were hurt, but the car had to be taken away by a tow truck. When the police arrived at the scene, the officer recognized the car. He offered Neilson a deal: if Neilson got him two autographed Crosby cards, Neilson wouldn’t get into any trouble.

Neilson was all in. The officer drove him back to Bouchard’s house and Neilson ran into Sidney’s room. Sidney was a heavy sleeper and didn’t really understand what was going on when Neilson shoved a sharpie and two cards into his face. He signed the cards and Neilson ran outside to punch his get-out-of-jail-free card.

When Sidney came up for breakfast the next morning, he was disoriented. He knew something had happened, but couldn’t quite remember. Neilson was struck dumb when he saw Sidney walking up the stairs; Neilson had left the uncapped sharpie in Sidney’s bed and Sidney had marker all over his face and chest. Sidney thought he’d been pranked, that Neilson had drawn all over him in his sleep. “He was pretty pissed off about that one,” said Neilson. “He was pretty upset once I told him the real story, and we got the permanent marker washed off his chest and his face” [116].

On the ice, it was Neilson’s job to bang things around. He was an enforcer and knew it—“I’m not out there to put the puck in the net,” he said. “But I go out there and play tough, play solid along the boards, skate hard and fight.”—but sometimes Sidney wouldn’t even need protection. He was strong and could handle things in the corners. Still, Sidney was grateful to have a player to look out for him. He wore extra padding on his forearms because of how often he was slashed [72, 89, 263].

“He looks out for me out there, that’s for sure. He’s a little bit of a protector, so it’s good to have him. There’s been a couple of incidents, especially in the pre-season, when guys have hit me from behind and the guys take care of it. Sometimes guys from the other teams won’t even fight when [Neilson] comes after them.” - Sidney Crosby [263]

Sidney wasn’t the only one to benefit from their partnership. He would tell Neilson to just put his stick on the ice and go to the net. That was all it took; Neilson scored several goals that year, all from Sidney. He was blown away by Sidney’s skill and hockey smarts [147].

“There were just plays that I would be a part of when I was playing on his line, and I’m just like, ‘How did he physically do that? How does he just know that?’ I’d come back to the bench and I’d just be mind-blown. There would be times where I’m just like, ‘Man, that’s incredible for a 16-year-old to be able to do that.’ And they weren’t just fluke plays—he would do them again and again and again. It was repetition. It was a pattern that he was able to figure out. He was just so much more advanced in the game.” - Eric Neilson [147]

“We chum around a little bit. I’ve shown him around,” said Neilson. “He's a quick learner at everything he does, and he’s learning French” [263]. Learning French became incredibly important for Sidney. Rimouski was 99.1% francophone, and Sidney would often turn to Bouchard for help preparing for French interviews [44, 321, 335]. “He likes to make fun of Eric, or fight with him, or laugh at my girlfriend’s English,” said Bouchard. “She doesn’t speak much English, and he’s trying to get his French going. He speaks to her in French and she talks to him in English, so it’s pretty funny sometimes. They both don’t understand what they’re saying” [295].

“We would have a rule where at the dinner table you could only speak French. At first it could be interesting, a little frustrating. But eventually I got to where I could carry on a conversation and say most of what I needed to say. I used it around the town, and people were really good about helping me along. It’s a big deal there to do it, and it means a lot to people.” - Sidney Crosby [The Rookie, p. 201]

Rimouski wasn’t a big place, and though the downtown had restaurants, nice clothing stores and plenty of shops, Sidney didn’t get out a ton [313]. He admitted he sometimes felt a little “stuck” at the billet, even when he and Neilson would try to have other guys from the team over to watch hockey games. Most nights he’d kill time by watching old 80s hockey games or action movies with Neilson—“they had seen just about every action movie stocked by the local video store” [295, Taking the Game…, p. 128, Most Valuable, p. 112].

It wasn’t the most riveting lifestyle, but Sidney was content. “The focus here is the team,” he insisted. “This team has had a lot of good players come through... and has done well developing them” [Taking the Game…, p. 128].

Sidney’s return to Halifax would curry some appreciation for Rimouski’s slow pace of life. Sidney and the Océanic rolled into Halifax on October 15, 2003. While the rest of the team packed themselves into a hotel, Sidney returned home and spent the night reading with his little sister, Taylor [198]. It would be a brief moment of respite before the entirety of the Maritime hockey world converged on him.

“[The media attention upon Sidney’s return] was a little much, there was too much hype. He would rather go in there, be one of the guys. It’s unfortunate because people who don’t even watch hockey show up and expect six points, and if he doesn’t do that, they say he had a bad game... But we don’t have control over that.” - Troy Crosby [313]

“When [the schedule] came out and I saw it, I wanted to see when we played Halifax. It’s basically my hometown—it’s right across the bridge,” said Sidney. “It will be the first time that a lot of family and friends have been able to see me play since I played for the Subways, so I’m looking forward to that” [297].

The game was sold out, and in the crowd would be several former teammates, coaches, and teachers. A hundred students from Astral Drive Junior High School were also in attendance [198, 265]. Sidney claimed he was fine with the spotlight. “If people come to the rink to watch me, that’s great,” he said. “It’s a little bit harder for us because there’s more fans cheering against our team. But at the same time, it’s good to have a lot of fans there. It’s more exciting that way, I think” [297].

“Whether there’s 10,000 or 1,000 fans there, we’re just happy to see him play. There have been a few people asking about getting tickets, but I don’t know that I can get that many. Most people have been good about it, and have gotten tickets on their own.” - Troy Crosby [265]

The locals were pleased to see Sidney again—Sidney’s midget hockey coach Brad Crossley told reporters that when Sidney was in town, he would always make sure to visit Crossley’s kids. “He’s just such a special person on and off the ice,” said Crossley. “He’s a very down to earth young man” [265].

“He’s just a great role model,” said Astral Drive Vice Principal Karen Dale. “I think it’s going to be wonderful that he someday may be, or is now, in a position where he can be there for others.” Sidney had returned to his alma mater the previous year (2002) to speak at an athletic awards ceremony and signed autographs for an hour and a half after the event [198].

The Crosby family had to adapt to Sidney’s celebrity status. “We’re definitely on a learning curve when it comes to that,” said Trina. “We’ve gone to some of his games and we’ve had to wait a substantial amount of time to see him because he’s doing all these interviews and signing autographs. But like anything else, you get used to it. It’s not long ago that he was one of those kids hanging around the Mooseheads dressing room waiting for an autograph, and that’s a big reason why he does it” [265].

“He completely understands the concept of enjoying things while they’re here because he knows they could be gone by tomorrow. It’s neat for him to be a role model, and for kids to knock on our door at Halloween and say ‘Is Sid home?’ It’s neat for us too, for the kids to look up to our child like that.” - Trina Crosby [Taking the Game…, p. 40]

Though Sidney thought it was important to be a role model, he also said he was still young: “I should enjoy being 16” [124, 198]. He felt his age when he stepped on the ice and looked into the sold-out stands full of his friends and family. “It just kind of flashed back,” he said. “You can remember sitting wherever and watching the games. It was a good time” [273].

The Océanic managed to get the win over Halifax, 2-1, though Sidney’s only point was an assist on the winning goal, which extended his point streak to 11 games [273]. The Halifax Mooseheads had several players who’d played with Sidney on various youth teams. They knew better than most that the average team couldn’t outplay Sidney on skill. They had tried to limit his space on the ice, but Sidney made himself hard to hit [289]. “We just played the man against him,” said Halifax defenceman Steeve Villeneuve. “You can’t play the puck against him because we know he’s got skills, so we play the man” [273]

“He’s just so strong. His body is so strong. He was more mature than all of us at that time. I don’t even know if there is a key to stopping him. I guess try to get in his head a little. He gets frustrated sometimes, so just get in his head [trash talk]. And hack him a little bit.” - Justin Saulnier, Mooseheads player [289]

Sidney’s November was incredibly busy. He tore up the league and people flocked to watch him play. The Rimouski Colisée had a seating capacity of 4,285 and could hold 5,062 standing-room viewers. On average, the Océanic boasted a crowd of 4,500 during Sidney’s rookie season [171]. Sidney admitted it was a little intimidating. “It’s been tons of fun, but it’s tough sometimes when you’re going in front of sold-out crowds every night,” he said. “That’s exciting for sure but at the same time there’s still a bit of pressure” [228, 16:08].

“You look at the stats, and you see that he’s already leading the Quebec League by that many points. In his first year, a guy just shouldn't be doing that. It’s a great story for hockey.” - Andy Nowicki, LA Kings scout [221]

People wanted to see the boy wonder for themselves. He put real fear into the eyes of defencemen, according to Daniel Doré, the Boston Bruins’ chief scout for the Q. Sidney had the ability to read a defenceman’s weaknesses almost instantly and make snapshot decisions based off of that information. He had confidence, the sheer nerve to try gutsy plays, and was unafraid to take hits from bigger players [Taking the Game…, p. 114].

Sidney considered his vision and his ability to anticipate plays to be his best assets. “I think it comes with knowing where to be at the right time,” he said. “When guys are bigger and stronger, you’ve got to outthink them and jump into open areas” [335]. Still, he wanted to improve his game. He wanted to block shots and be an all-around player, though his coach urged him not to block with his body [88, 205]. His coaches emphasized that they want him to grow his skills his way. “Sidney has to be his own player, not what others want him to be,” said Labonté [335].

“It’s a long season and I’ve got to work on bettering myself every day. I can’t be a different player. I just have to play the way I know how and let people form their own opinions.” - Sidney Crosby [335]

The team’s management was keeping a careful watch on Sidney as he burned through his opponents. He was putting up numbers at a “feverish” rate and led the Q’s scoring race. Frustratingly, Rimouski was situated right in the middle of the league’s territory, meaning that a trip to Rouyn or Cape Breton could stretch as long as 12 hours. Rest was “an issue,” and the Océanic was not going to wait for players to look tired before resting them. “We have to force Sidney to cool down because he isn't happy when he's not on the ice,” said Labonté [132].

People’s opinions of Sidney were, on the whole, very positive. He did a few fundraiser skates for minor league hockey in November, where children would gather near the Océanic bench, cheering and begging for autographs. Many of them wore replica Crosby Océanic jerseys [171].

“It’s pretty neat, because I remember wearing other guys’ jerseys as a kid, but at the same time it makes you want to do that much better. It motivates you to see kids are looking up to you enough to wear your jersey.” - Sidney Crosby [171]

Sidney was happy to oblige the kids, adamant that he had to give back in some way. “I can remember being in Cole Harbour and seeing the Mooseheads in their training camp,” he said. “Half the guys’ autographs I got didn’t even make the team when I saw them at Cole Harbour Place, but I was so happy to have their autograph” [284]. It was the least he could do to give other kids the same happiness.

“I understand [media is a] part of hockey and I’ve gotten used to that. I take care of it when I need to take care of it. I’m worrying about being a better hockey player and proving myself in that way. If media interviews and signing autographs comes along with it then I’m more than happy to do that.” - Sidney Crosby [205]

His success and popularity earned him an invite to the 2003 Canadian Hockey League RE/MAX Canada-Russia Challenge Series as one of the QMJHL all-stars. It was his first appearance on national television since the Dartmouth Subways made it to the Air Canada Cup final. “I don’t think he is as excited about being on national television as he is about playing Russians,” said Troy Crosby [48].

A select Russian team was making its way through Canada, playing six games against 3 CHL all-star teams (an OHL team, a QMJHL team, and a WHL team) throughout November [142]. The Russian roster was young and small, with 11 players under 19 years of age and most forwards under 6 feet tall. The roster was relatively unknown—only one Russian was a veteran from the 2003 World Juniors gold medal team, and Alexander Ovechkin was playing for Moscow Dynamo’s senior team instead of the select roster [143].

Sidney’s schedule was jam-packed. He played 5 games in 6 days, squeezing home games in Rimouski between the two Canada-Russia games in Halifax [133]. He scored three assists over the two-game series and had only a single goal, scored in Canada’s first game—a 3-2 loss in which Russia’s goalie, Konstantin Barulin, stood on his head to eke out the win. Canada had more luck in the second game, winning 6-3 [221, 144, 145].

Sidney was hungry for international competition again. In an interview at an Italian restaurant in Rimouski, Sidney wore a Team Canada golf shirt and admitted on his way back from the restaurant’s bread bar that he “would love to play” for the 2004 World Junior team [131].

He had a decent shot at making the roster—his performance at the U18 tournament had been commendable. “He’s very competitive and plays with a lot of bite,” said Blair Mackasey, Hockey Canada’s head scout. “He’s physically stronger than a lot of people think. Very strong legs” [335].

The end of Sidney’s first November in Rimouski would bring a test not of his physical abilities, but his mental ones. On November 28, 2003, Sidney scored a “lacrosse-like” goal against the Quebec Remparts, picking the puck up on his stick and flinging it past the goalie. Don Cherry, a commentator with Hockey Night in Canada, took issue with how Sidney celebrated after the goal; the Océanic had already been leading 4-0 [8].

Cherry insisted that Sidney had made a spectacle of himself on the ice, and spectacles invited retaliation. “I’m trying to help the guy, warn the guy to stop it,” Cherry said. “He’s a good kid, a nice kid. He didn’t mean to embarrass the [goalie] but he did. The agents won’t tell him because they don’t want to lose him... I’ll tell him because I want to help him” [150, 179].

Then he took a crack at Sidney’s parents.

“His parents evidently don’t know anything about that stuff. Someone should have told him not to do it,” said Cherry [Taking the Game…, p. 118].

The Crosbys sent an email to Cherry’s “sidekick,” Ron MacLean, arguing Cherry’s commentary was inappropriate. Troy Crosby said Cherry was “ignorant” and “made an issue out of something that basically put a bounty on a 16-year-old’s head. He’s already a target as it is and now it’s basically okay to go out and hurt him” [42, Taking the Game…, p. 118]. Cherry blustered forward, and when he interviewed Red Wings player Brendan Shanahan the next week, Shanahan said he’d be “looking to take the head off” any player who attempted that goal against his team [66].

Sidney had actually been practicing the move for weeks and had taught himself how to do it on both his forehand and backhand. He’d spent many practices working on it and encouraging his teammates to be more adventurous with the puck [170]. He was proud of his skill and so was his team. The Océanic was selling DVDs of the goal for $8.69, calling it “Le fameux but du 87” [42].

Though the footage was splashed on television screens across Canada, Sidney hadn’t originated the move. Made famous in 1997 by University of Michigan player Mike Legg, it had won Legg an ESPY award for most outrageous play of the year [The Rookie, p. 176]. It won 16-year-old Sidney public criticism on a television program watched by nearly 2 million viewers [83].

“I don’t taunt other teams. I’m an emotional player and when I score a goal, I’m going to be happy. I worked on a move that I tried for the first time in that game and it worked. That was basically the point behind it. It wasn’t to taunt or show off. I try not to be that type of player and I hope people realize that’s not the type of player I am. It’s a move I saw in the NCAA and I thought I’d give it a try and it worked, so I was happy.” - Sidney Crosby [208]

A few days after Cherry’s broadcast aired, Sidney calmly told reporters, “I’m not shaken by his words. It’s his style to make controversial remarks. I can’t please everyone” and “I know the unwritten rules. My father taught me about respect. I wasn’t trying to embarrass anybody” [66, The Rookie, p. 176]. Luckily for Sidney, the majority of Canadian media agreed that Cherry’s comments were out-of-line. Back in Halifax, some locals called for a boycott of HNIC [Taking the Game…, p. 117].

While the Cherry remarks were the most high-profile incident, they were not the only criticisms leveled at Sidney that year; he had “gotten into the habit of complaining to officials,” and people were taking issue with it [8]. “He faced greater expectations and pressure than perhaps any Canadian player since Wayne Gretzky, and when those forces combined with his perfectionism, they could boil over” [97].

“In Rimouski if I played bad, and back then I could still play bad and still get a couple points, they had outdoor rinks I’d go to. The coach might tell us we had the next day off, but I’d get the trainer to put pucks and skates in my car so the coach wouldn’t see. And I’d go out and shoot pucks at night by myself. Oh, it was the best. I didn’t have anyone telling me what to do. No one was telling me to dump pucks in or play the system. No one cared if I missed or scored. It was just me out there. That was probably one of the best therapies I’d ever done over those two years. That was my spot, my place.” - Sidney Crosby [The Rookie, p. 40]

With December came the ultimate palate cleanser: an invitation to try out for the Canadian IIHF Ice Hockey World Junior Championships team [208]. It was a childhood dream come true. “It’s like religion up there,'' said Sidney. “Over Christmas break, you’re not worrying about opening gifts. You’re waiting to watch Team Canada play in the World Junior tournament” [134].

On December 1st, Hockey Canada announced that Sidney would attend their evaluation camp in Kitchener, Ontario [208]. He was the youngest invite by 23 months and only the sixth 16-year-old to ever be invited to the U20 program [47, Taking the Game…, p. 115]. The second-youngest player, Stephen Dixon, also hailed from Nova Scotia. It had been 21 years since a player from their province made the roster [47].

“I’m happy for the opportunity to play for Team Canada, but I’m not all the way there yet. I’ve got a lot to prove. I want to have a good camp. I can’t be nervous or go in scared... I’ve played with older guys all my life. I don’t step on the ice thinking, ‘Wow, I’m playing with 19- or 20-year-olds. Once you’re on the ice, you’re all equal.” - Sidney Crosby [208]

From December 11-16, the 36 invitees scrimmaged and practiced to earn spots on the 22-player roster. They also played two intrasquad games and two games against an Ontario University Athletics all-star team. Blair Mackasey, Hockey Canada’s head scout, had spent the first few months of the hockey season monitoring junior players across Canada and was thoroughly impressed by Sidney’s skill [232, 349]. “Sidney is a tremendous talent,” he said. “He’s one of the few players that excites me and can get me out of my seat” [154].

In his first game against the university players, Sidney was tentative at first—“I think I was a little bit hesitant because you’re playing against older guys and you don’t want to get caught in their hooks... I just realized that I can go in there and get away from it. They’re 25 years old, but I have good balance... I could get through those hooks and sometimes I could finish guys. I could knock ‘em down.” By the third period he’d gotten his skates beneath him and was playing like he owned the ice [357]. After a three-assist night during Team Canada’s 9-1 clobbering of the Ontario University Athletic Association, Sidney had clearly earned his spot on the roster [355].

In Kitchener, Sidney roomed with Jeff Tambellini (whose father Steven Tambellini had roomed with Wayne Gretzky during the 1978 World Juniors). The two would become linemates as camp wore on. “There is great chemistry between us and we’re becoming the best of friends after four days,” said Tambellini, “and it’s really easy to play with a guy like that” [304]. Sidney didn’t sleep much; every morning he woke at 4:30 a.m., when the coaches would inform players if they had been cut [47]. “He was so nervous,” said Tambellini. “He was playing with the weight of the world on his shoulders. But he’s a professional at 16 years old and I’m sure he’ll be able to handle it” [222, 304].

“I have an opportunity to play for Team Canada so it’s not something that I’m saying ‘Next year, [or] I’m just happy to be at the camp.’ It’s not that at all. I came here to make the team. I’m not going to be happy if I get sent home.” - Sidney Crosby [196]

As the days went on, Sidney became more comfortable but was still cautious. World Juniors is considered a 19-year-old tournament, so Sidney at 16 likely wouldn’t be seeing more than spot duty. “I’m pretty pleased how he’s doing right now,” said Mario Durocher, Team Canada’s head coach, “but it’s a three or four-day camp so we’ll have to see how he can deal with the bigger guys and the older guys” [196].

“There’s a little time of adjustment. This isn’t a normal level of hockey, this is the best guys in the world and you have to take a little time, and readjust your game to that.” - Sidney Crosby [355]

Sidney was plainly a young teenager adjusting to more intense hockey, all while dealing with incredible media attention [304]. Newspaper articles bit into him, reporting that he wasn’t standing out during the intrasquad and exhibition games [193]. Autograph seekers swarmed Sidney to the point that Hockey Canada limited the number of items he was allowed to sign and had him entering and exiting Kitchener Memorial Auditorium from different doors [196]. When a television station asked him to don an authentic Canadian jersey for an interview, he declined [47].

“I didn’t want to jinx it. To me, it wasn’t right. There is a lot of sweat and hard work that goes into earning the right to wear Canadian colours. Yes, I’m superstitious. But I also wanted to work hard and prove to the coaches and my teammates that I belong on this team.” - Sidney Crosby [47]

Sidney very much wanted to fit in with his teammates, especially after his stint as the black sheep in the Czech Republic. It was hard with the media circus following his every move, but Sidney was certain that his fame hadn’t hurt his reputation with the other players. “I think the guys understand,” he said. “These guys are great players as well and they’re out here doing interviews the same way I am. I might be doing a few more, but they don’t get mad. They accept it. It’s part of hockey. It’s not something we really talk about” [196].

Even though the team was young, with half the roster only aged 18, many had at least some international experience. Their collective experience helped them bond quicker, said Tambellini. “This is probably one of the tightest groups I’ve seen come together after four days. It’s something that you can’t teach, it’s either there or it isn’t. This is a special group, I think” [184, 304].

Among them were only two returning players from the previous year’s team: Gatineau Olympiques forward Maxime Talbot (who was chosen as one of the assistant captains), and Cape Breton Screaming Eagles goalie Marc-André Fleury, who was eager to rope Sidney into a bet [47, 92]. After a practice, Sidney beat Fleury on 2 out of 3 shootout attempts to win a soft drink. Sidney was thrilled to face Fleury, who’d been drafted first overall by the Pittsburgh Penguins earlier in the year. “It was awesome. It’s a big challenge,” Sidney told reporters. “Even if he stops you, he plays in the NHL. Everyone wants to shoot on him. I think there is a lot of pressure on him” [235].

By the end of the camp, Sidney had left his mark. “[Sidney] passed his tests here with flying colours,” said Mackasey. Coach Durocher was so impressed that he considered giving Sidney regular shifts during the tournament and putting him on the power play. “He’s not going to be on a checking line, though,” Durocher remarked. Sidney was eager to contribute in any way he could. “I’m pretty much ready to accept whatever they want me to do,” he said. “I just want this team to win a gold medal” [184].

When Sidney was named to the team on December 16, 2003, he was only the fifth 16-year-old to ever be named to the roster, and the second-youngest player of all time [32, 41, 47]. “It was a very simple decision on our part,” said Mackasey. “He was going to make the team if he was good enough to make the team” [32].

This was also the perfect time for Fleury to enact his revenge. Right after the official team photograph, Sidney got a shaving cream pie to the head, courtesy of one Québécois goalie [214].

Ten days later, Sidney and Team Canada traveled to compete in the 2004 World Junior Ice Hockey Championship, held in Helsinki and Hämeenlinna, Finland, from December 26, 2003 to January 5, 2004. Sidney was “acutely conscious of being just another member of Team Canada” [327]. He was the runt of the team, despite the numbers he was putting up in Rimouski, and that role came with rules. For one, he was tasked with helping the staff clean up water bottles and pucks after each practice. “I’m a rookie in Rimouski, and I’m the youngest guy on the team. I know my place. Somebody else will do it next year,” he said when asked about it by the media [41, 339].

“I think I’m a student and I want to try things. I want to improve myself and do things that guys maybe never thought of. That’s what makes guys creative; that’s what makes guys good. I’m not trying to change hockey or anything like that, but if I can help it, that’s good and I want to do that. That’s the fun part.” - Sidney Crosby [327]

As the only Canadian player under 18, Sidney had to wear a full face mask on the ice. At this point in NHL history, few professional players even wore visors. Don Cherry was particularly eager to call players wimps for wearing any sort of face protection [140]. Sidney was the target of a more friendly sort of bullying when his teammates caught him napping on New Year’s Eve and rolled the mattress around him, taping it shut. They carried the mattress into the hall, onto the elevator, and sent him on his merry way down, only clad in the mattress and his boxers. When the elevator doors opened, it was team manager Ron Pyette who found Sidney and freed him [151, Taking the Game…, p. 119].

Sidney took it all in stride. It was teambuilding according to him. “It was great to be in a situation like that,” he insisted [Taking the Game…, p. 121]. He’d grown close to Tambellini as well, both on and off the ice. “We’ve been attached at the hip for the past 20 days,” said Tambellini. “We’re sensing each other in the spots. It’s exciting to get to that stage.” The only downside Tambellini saw to rooming with Sidney was his music taste. “He just listens to too much music. I have to get him to turn off Shania Twain every night” [130]. Shania Twain, Tim McGraw, and the Dixie Chicks were some of Sidney’s favorites [42].

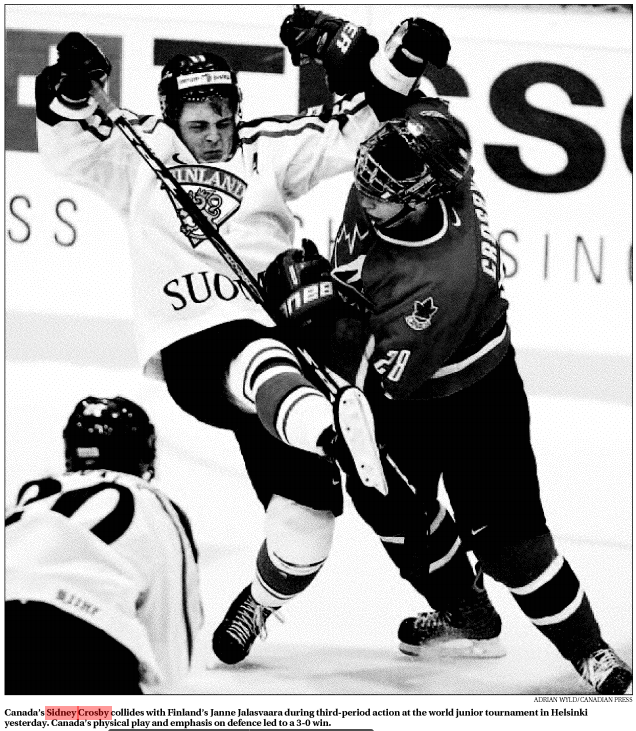

Sidney adapted quickly to U20 hockey, but not quick enough for his taste. After the tournament-opening game against Finland, he admitted he had some nerves. “I didn’t know what it was going to be like and I got out there and I kind of got caught watching a little bit. And then I figured out, hey, if I skate I can play, there’s no reason I can’t,” he said. “So I just told myself to play my normal game and I can contribute. From there, I’ve had to pick up my speed on defence. I mean, you’re playing against the best players in the world” [326].

It was a slow start to the tournament for Sidney. Including the 2 exhibition games during the selection camp, pre-tournament games against Sweden and Austria, and the first game against Finland, Sidney went 5 games without a goal [181]. “He’s had a bunch of chances and when a goal scorer doesn’t score it can get frustrating,” commented Assistant Coach Dean Chynoweth [153].

The hype Sidney received leading up to the tournament was significant. In a “10 players to watch” article in The Edmonton Journal, a writer said that while Sidney wasn’t Canada’s best player, he was the most interesting player to watch. “Deceptively fast and wonderfully creative,” Sidney was a draw for the team, and his feistiness turned heads. The weight of the public’s expectations rested heavily on him [354].

The dam cracked against Switzerland with a “beautiful, highlight-reel” goal. At 16 years and 5 months old, Sidney became the youngest player to ever score in the World Juniors tournament when he carried in the puck down the right wing, swerved around a defenceman, and poked in a puck to complete Canada’s 7-2 win over the Swiss. The puck was grabbed by Team Canada publicist Andre Brin and sent to the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto [153, 181, 326, 353].

“I knew it was going to come. I mean, there have been games where I haven’t scored before... Sometimes when you get one, two and three come nice and fast. But I’m not worried about goals at all. If I’m working hard, trying to make things happen, then putting the puck in the net and helping our team is going to take care of itself.” - Sidney Crosby [353]

“You could tell by [Sidney’s] body language that he needed that goal,” said Chynoweth [153]. Though Sidney claimed he wasn’t worried about goals at all—that he only cared if he was helping the team—he was clearly relieved. The Swiss had been physical with Sidney all game (including a high crosscheck to his neck that an ESPN writer described as an attempt to “decapitate” Sidney [66]), and scoring raised his spirits, even though Sidney’s goal caused a bit of friction within the team. Sidney had scored on a two-on-one, and some of his teammates thought he had been selfish for not passing the puck to his teammate, who was wide open in front. Sidney had scored on a high shot into the net from a terrible angle [41, 181].

Sidney scored again against Ukraine, but it was another blowout win for Canada. His points were entertaining when he tallied them with pretty passes and slick moves, but he played less and less each game [Taking the Game…, p. 119]. He was buried on the fourth line, and some suspected it was a consequence of Team Canada’s coach, Mario Durocher, also being the coach of one of Rimouski’s rivals. That Sidney was so young also played into the decision; team officials wouldn’t want to insult an older player by letting a 16-year-old play bigger minutes [66].

“You have to be careful, you can’t lose sight of the fact that you’re playing against the best 19-year-olds in the world. That’s a challenge for anyone. To ask a 16-year-old to [do] it, that’s something to consider. With any younger player, you have to put them in a situation where they can succeed.” - Blair Mackasey, Hockey Canada head scout [313]

In the end, though, Sidney was outmatched. “Fun to watch,” as one writer said, “but [was] probably a year away from being an impact player” [223]. Against the low-end teams he was able to hold his own, but against the high-end teams his size and inexperience became limiting factors. “I would be very surprised if [opponents] didn’t have his name circled on the board,” said Chynoweth [353]. Still, he drew compliments from teammates and scouts alike for his performance. “I don’t think it was fair to expect Sidney to play a big role with the team—it’s a lot to expect of a 17-year-old, forget about a 16-year-old,” said teammate Mike Richards [Taking the Game…, p. 118-120]. “His play has shown that he is good enough to be here,” added Dion Phaneuf. “But I think you see that he is a 16-year-old in the corners sometimes because he gets out-muscled. But that is something that will improve as he gets older” [339].

“I think it’s burdensome to be equating someone to players that have gone on to amazing, incredible accomplishments over 15 to 20 years. I think it’s premature to try and heap this on a 16-year-old kid. He’s fun to watch. He has a passion for the game that everybody—fans, writers, everybody—likes to see and that’s really important. But everybody’s trying to find the best doctor in the 10th grade. Things can change dramatically as [kids] mature or don’t mature.” - David Conte, New Jersey Devils Director of Scouting [326]

Ultimately, Sidney underperformed in the tournament, though some scouts felt he had been underutilized [66]. Through it all, he showed he had adaptability, guts, and the ability to be dangerous on the ice. Despite the intense media scrutiny and his adjustment period to U20 hockey, he managed to be “just another 16-year-old kid” [326]. After calling him a prodigy, the media would in the same breath say he was “unfailingly polite and so Canadian in determined humility...” [162]. One writer said his stand-out memory of the tournament wasn’t watching Sidney play, but watching Sidney walk around Helsinki’s airport hand-in-hand with seven-year-old Taylor [126].

Back in Cole Harbour, the locals were bursting with pride over their golden boy. 150 people gathered at the local Sand Trap Bar and Grill to watch the gold medal game between Team Canada and Team USA. The bar had a rusty sign propped up outside that read “Go Sid.” After watching the tournament take place in Halifax last year, they now got to see Cole Harbour’s son go for gold [149].

It wasn’t meant to be. Despite a strong start, Canada’s two-goal lead vanished in the third period as the Americans netted three. The crowd grew anxious. “It’s not over till it’s over,” shouted Girard Birette, a local. “Come on, Crosby, You can tie it baby, you guys can do it” [149]. American goalie Al Montoya foiled Sidney with a glove save on a 2-on-1, and then a fluky bounce off of a Canadian body slid past Fleury. The game was over. America had won [93].

“I don’t remember it that well. We had a number of chances in the third, but mine specifically, you’d have to refresh my memory on exactly what it was. I probably chose to forget it. It’s probably better that way.” - Sidney Crosby [93]

Sidney was “devastated” according to his father. He finished the tournament with two goals, four assists, and a silver medal [93]. In the locker room, Canadian captain Dan Paille told the team to remember the feeling of loss and make sure it never happened again [259]. Sidney took the words to heart. “I’ve been thinking about [next year’s tournament] ever since after the game,” he said. “I want to make sure that next year I kind of finish what we didn’t finish this year” [190].

“It’s tough. You’re 16 years old and you have the chance to win a gold medal, World Juniors. Chances like that don’t come all the time. It’s hard to get to the gold medal game, and you want to take advantage of it when you get there. But I’m hoping I’m going to get another chance next year.” - Sidney Crosby [259]

Sidney’s silver medal came to rest in the Crosby family’s trophy room. “He doesn’t like that one much,” Troy told a reporter with a smile [49]. Sidney returned to Halifax from Toronto on January 6. He’d missed 11 QMJHL games while playing in Helsinki, and would miss 2 more against Lewiston so he could stay in Cole Harbour and rest. He was exhausted both emotionally and physically from the loss, and his body had taken all kinds of punishment. “I’d say I’ve been a target since Christmas,” he said. “I wouldn’t say everything is clean—everyone is guilty of giving a little extra once in a while, but that’s hockey and that’s the way it goes. I’ve seen it before. I’ve just got to get better and get through it” [171, 259, 267].

The Crosbys were grateful to have Sidney home, even just for a short while. “It’s not about the quantity [of time] as much as it is the quality,” said Trina, who had been making scrapbooks filled with newspaper clippings about Sidney [45, 265]. The Crosby family room had turned into a museum full of “Dozens of pucks, all neatly marked with hockey tape bearing the record and date broken, medals and jerseys, his first interview at the age of 7, a recent five-page profile in Sports Illustrated, the cover of The Hockey News, all neatly framed” [49].

Though he was already living an extraordinary life, Sidney was adamant about being just another kid. When asked when was the last time he felt like a normal kid, he said, “Um, two minutes ago,” and laughed. “I feel like a normal kid all the time. When I came into the office today, there was a stack of mail that I guess most 16-year-olds don’t get. That’s the only thing that’s kind of different—the interviews and the mail. But with everything else, I’m just a normal 16-year-old” [170].

“All [my parents] told me was to be myself. They said people would compare me to other players, but I can’t be Eric Lindros or Vincent Lecavalier. I can only be myself. They have taught me not to take things for granted and not to look too far into the future.” - Sidney Crosby [270]

Sidney was still close to his family and enjoyed being home while he could. The Crosbys were able to make it out for games occasionally, including trips with one of Sidney’s grandmothers that were “some of the best family memories” the Crosbys had [249, 7:23]. Sidney also, when asked if he could pick anyone he wanted to watch him play, chose his great-grandmother. “She’s pretty old and she’s never gotten to see me play hockey,” he explained. “She doesn’t get around a lot, but if there’s someone that I would like to see me play, it would be her” [170].

An article in the Halifax Daily News that year had said the Crosby family was “missing mortgage payments and scrimping on groceries to pay for hockey equipment and other hockey-related costs” [7]. Sometimes they struggled “to buy oil for a few months’ heat, new skates each season, and cash enough to pay for the next tournament motel” [8].

Financial difficulties had been long-present for the family; in his first years in minor league hockey, Sidney and his mother would spend Sunday afternoons going door-to-door to deliver the weekly shopper so they could afford tournament and league fees [8]. “I can remember there would be guys playing ground hockey on a Sunday and he wouldn’t be able to play until he was finished doing the flyers,” said Troy. The shifts were usually five hours long. “Stuff like that and other life lessons stuck with him” [365]. Traveling for tournaments was how the family vacationed [The Rookie, p. 66].

“You know, if people are going down the street they often look down on people who are doing jobs like delivering flyers or anything else like that. But we were just working hard and there was nothing wrong with teaching him that lesson and being proud of that.” - Trina Crosby [365]

“...I can remember they had to take on an extra job just so I could keep playing hockey. We did things just like that so I could continue to play a game I love.”

- Sidney Crosby [7]

“My parents sacrificed a lot. Up early in the morning, driving me to the rink. Never complained when they had to buy me hockey gear. I always had good equipment. Sometimes that wasn’t so easy for them, and without that, I wouldn’t be here today.” - Sidney Crosby [43]

As a 16-year-old major junior rookie, Sidney was entitled to a $35-a-week stipend as well as room and board, but there were rumors floating around the hockey world that the Océanic was “clandestinely” paying him $150,000 as well as adding an attendance clause into his contract. Troy Crosby and Pat Brisson made it known that they had an “agreement” with the Océanic that would merely cover Sidney’s college costs (only if he chose to attend, which would be unlikely given that his major junior career made him ineligible for NCAA hockey), but they denied the rumors about the payment and attendance clause [19].

With or without the rumored salary from the Océanic, Sidney was already making money from hockey. He had his deal with Sherwood at 15, and was the first QMJHL player to sign a contract with a sports goods manufacturer [85]. His big financial break came at 16, when Jeff Jackett at Pepsi Co. set off on a mission to secure Sidney Crosby as the face of Gatorade. Jackett pursued Brisson across the country in attempts to get a meeting and had to present his pitch to Brisson and Troy Crosby multiple times before even meeting Sidney. Sidney eventually signed an agreement for $300,000 CDN over 3 years—more than double what Gatorade was paying the two other hockey players on its roster (José Théodore and Todd Bertuzzi) combined [86].

“When he was about 16, he told me, ‘I think we have enough right now. What do you think the guys in the NHL think of me? I’m not even playing there.’” - Pat Brisson [84]

When Sidney returned to play for the Océanic, one of the team’s first stops was back in Halifax to face the Mooseheads. On January 13, 2004, he tallied an assist, two goals, and an empty netter to push the Océanic to a 5-3 win [285]. The Metro Centre was packed as Maritimers came to see Sidney after his first World Juniors appearance. 10,595 people attended the game—it was one of five games during the season to net over 10,000 viewers [345].

The once-adoring crowd turned on Sidney, booing when Halifax's Petr Vrana was put in the box for hooking Sidney in the third period. When Sidney was sent sprawling onto the ice by Halifax’s defense minutes later, they cheered [285].

Sidney had a more welcome reception in Rimouski. “This town is perfect for him,” said Troy Crosby. “The fans are supportive. It’s a really good place for him to grow as a hockey player. They appreciate hockey here, they have a great knowledge of the game” [221].

Sidney was trotting out his roughshod French to connect with the community. He’d been trying to improve his language skills by instant messaging with locals or speaking in French with Neilson. “It was pretty weird,” Sidney said with a laugh. “But we knew why we were doing it” [44, 381].

“English-speaking guys have excelled in the league. Pat LaFontaine is one. My dad played against him. He said [LaFontaine] was really liked. My father told me it doesn't matter what language you speak. The way you handle yourself and the way you play is the way you earn respect.” - Sidney Crosby [Most Valuable, p. 111]

Sidney wanted to learn more French and told reporters he had a goal to do interviews in French the next season. He felt like he could understand the language well enough, but his speaking skills needed more practice. “It’s going to be a matter of time,” he said [Taking the Game…, p. 129].

“When he went out in the community, he was talking to everybody, whether it was in stores, the supermarket, at restaurants. He was trying to speak French. I think, no matter the situation, he wants to do the right thing. When he passes kids in a playground, he stops and gets in the game with the kids... he makes time for everybody and he's always respectful.” - Suzanne Tremblay, Océanic season-ticket holder and former Bloc Québécois MP [Taking the Game…, p. 115]

He was active around Rimouski; “Everybody has a story about Sidney and the team,” said Pierre Blier, a local. “Sidney and these players out here playing [shinny] on the little outdoor rinks with little kids and their fathers—things that these kids will be able to tell their children about one day. The one funny story I have was Sidney coming into the Tim Hortons doughnut shop and there were a bunch of kids, little kids, sitting at a table. So Sidney bought a box of doughnuts and gave it to them. After he left they were trying to figure out whether they should eat them or keep them as souvenirs” [Taking the Game…, p. 125].

“When you are away from the rink people recognize you once in a while, but it’s good for me. Some little kids might see me as a role model and that makes me make sure that I take time and see the kids. I think it helps me become a better person, for sure.” - Sidney Crosby [205]

Sidney even acted as a sort of political balm in the Québécois town. The Liberal government had lost popularity in early 2004 and was met with an upswing in support for the Quebec sovereignty movement across the province [342]. “There are people who believe in an independent Quebec and they can still like and respect Sidney as a player and as a person,” said Blier. “[Sidney] is away from politics. Maybe he shows some people that there’s decency and respect in many places, not just in our town...” [Taking the Game…, p. 222]. Sidney also received glowing praise from former Bloc Québécois MP Suzanne Tremblay [44].

“He’s an incredibly well-grounded young man. The way he’s managed to keep his composure in the face of all the attention that he’s generated and all that he has to go through on the ice, it amazed me. And people just like him. You come away from meeting him knowing that he’s something special.” - Pat Brisson [Taking the Game…, p. 135]

Sidney’s teammates all liked him too; he was folded into the team and hazed just like any other new kid. His hair was slicked with Vaseline at one point, and it didn’t come out for a week. He was also made to dress up like Marilyn Monroe, but... poorly [91].

He would need the camaraderie. Come February, the Océanic’s management grew concerned over the treatment Sidney was seeing on the ice. Despite his teammates’ willingness to throw down their gloves on his behalf, the on-ice abuse Sidney faced reached a fever pitch. The Océanic was fed up with refs “putting away their whistles” while Sidney was harassed [66].

“Teams wanted to intimidate me. And after [World Juniors] it was bad too. In one game I had five fights in the first 15 seconds” - Sidney Crosby [66]

“It wasn’t a normal year for [all the infractions], I guess. That stuff doesn’t happen all the time. A lot of it was out of my control. That’s what helped me the most. It was out of my control and I realized that, so it didn’t affect me.” - Sidney Crosby [136]

On February 12, management was enraged over referee Richard Forest’s work in a 4-3 loss to the Halifax Mooseheads [267]. The next day, the Océanic said they wouldn’t dress Sidney for games against the Lewiston Maineiacs and the Drummondville Voltigeurs the coming week. Tickets were sold out for both games [156]. “I think we play tough against him, but we play fair,” said Lewiston coach Mario Durocher, who had coached Sidney at World Juniors. “He’s a tough kid. He’s not a Gretzky-style hockey player. He’s going to the net, he’s driving the net, so he’ll have to pay the price for that” [267].

“You get a lot of sticks hitting you in the back. They say lots of stuff. They tell you to keep your head up. If you’re having a rough night, they’re asking you, ‘Where are you tonight?’ No matter if you get three goals, or nothing, they’re still going to chirp at you. Nothing really surprises me. I’ve pretty much heard it all.”

- Sidney Crosby [267]

Lewiston had beaten the Océanic in every game thus far that season, winning 6 in a row and gunning for more. Lewiston was 3rd in the Q’s Eastern Division, just a scant 5 points behind the Océanic (the Chicoutimi Sagueneens were leading the division by a single point over the Océanic). Lewiston had several games in hand over both teams and was aiming for a coveted bye through the first round of playoffs, which was granted to the first place team in each of the Q’s divisions [343].

“We were worried about Sidney running out of gas. He had been playing since August. He had travelled a lot. We ask him to play a lot. It would be tough on any player but especially a 16-year-old who hasn’t played at this level before or played as much. We were already in the playoffs. Really, it was for his own protection. We were just worried about him getting injured—not getting gooned.” - Donald Dufresne, Rimouski Océanic Coach [Taking the Game…, p. 132]

The Océanic claimed that officials ignored infractions against Sidney. The league commissioner, Gilles Courteau, saw it differently. “[Sidney] is our bread and butter,” said Courteau. “If vicious hits are made, they should be punished. But Sidney can’t be treated differently than other players in the league.” Some thought the Océanic was playing power games to manipulate the league into lavishing Sidney with preferential treatment. Pat Brisson attended several games over the week and “likely had input in the team’s decision” [267].

“The ref is all over him because that’s Sidney Crosby. Everywhere we go, Sidney makes the fans react. Every time he does something wrong, the ref is going to call it, for sure.” - Guillaume Lavallee, Rimouski Océanic goaltender [296]

Courteau wasn’t pleased with how the Océanic handled their complaints. Though he said there were no league rules preventing a team from healthily scratching a player in protest, he said the Océanic didn’t use the proper channels to resolve their complaints. He found out about Sidney’s benching through the media instead of direct communication [282].

“We have a procedure established at the league level that if you have something to complain about, you know what you have to do. You have to send something in writing, plus a copy of the incident on tape. It’s our job and responsibility to look at it and get back to the team with the proper action, if there is any to take... There’s one thing to put a player aside for a game, but I would like to get some clarification from Rimouski about why they have the intention of having Sidney Crosby aside for a couple of games.” - Gilles Courteau, QMJHL commissioner [282]

Rumors started circulating that Sidney was considering quitting the Q to go play in Europe [156]. Doris Labonté, the Océanic’s General Manager, first read the rumors in a Daily News column and didn’t take them seriously until Troy Crosby mentioned the possibility to him [282]. “The lack of protection for Sidney means that he may perhaps consider this option,” Labonté said. “If I was his parents, I would react the same way” [267].

The move wouldn’t be unprecedented; Wayne Gretzky himself had left junior hockey to play in the WHA, as his advisors were afraid a cheap shot would end his career before he even reached the NHL [155]. IMG representative Richard Paquette told reporters Europe was a real option for Sidney and that he and Pat Brisson would be meeting with Courteau on February 16 to discuss the state of officiating in the Q [282].

“It’s to discuss what the league, what we and everybody can do to try to protect him and improve the situation,” said Richard Paquette. “We don’t want to be treated differently than any other player... Let’s improve the refereeing—not just for Sidney Crosby, for everybody” [282].

“Now it seems that the referee, everywhere you go, they’re so afraid that they’re going to be told, ‘Oh yeah, we know it's Sidney Crosby, you protect him so much.’ Now it’s been the opposite. They don’t call anything. You know Sid. He doesn’t want to complain; he just wants to play hockey. It’s getting frustrating for him because he’s been the victim of a few shots, and when he looks at the ref or protects himself, he’s the one that gets thrown out. Physically and mentally, he doesn’t know what to do anymore.” - Richard Paquette, IMG representative [282]

It was a PR disaster, and much of the criticism was leveled at Troy Crosby; many thought that he had been pushing for such a move, though he denied it [66]. “It didn’t come from Sidney or me,” Troy said. “Sidney can handle himself. That’s the way it’s always been” [Taking the Game…, p. 130]. Don Cherry involved himself again, lambasting the Océanic for the move [155]. Things peaked when, in the midst of the controversy, the Océanic decided to play Sidney at an away game against the Quebec Remparts, a team owned by another member of the Tanguay family—securing a profit for the Tanguays while jeopardizing sell-out crowds for other franchises [267]. Of the 13 franchises the Océanic played against, 10 of them sold the most tickets when Sidney was in their building. Over the course of the season, the Q had improved its attendance numbers by 64,425 people—around 153 more per game [345].

Some media members speculated that the Océanic wasn’t benching Sidney in protest, but actually trying to rest him before the playoffs. If the Océanic won the regular season, they’d earn themselves a bye through the first round of playoffs. It was possible that the Océanic was willing to sacrifice that bye (by benching Sidney) in order to play in the first round of the QMJHL playoffs and rake in the revenue from those games. “Whatever the reasoning, it’s incumbent on the team and the league to keep Crosby and his family happy,” wrote John MacNeil for The Halifax Daily News. “He’s worth that much and more” [267].

By February 18, the Océanic had backed down. They confirmed to Lewiston that Sidney would be in the lineup after all, and Sidney helped lift the Océanic to their first win over Lewiston that season, a 3-0 shutout. The Océanic then rolled into Drummondville and beat the Voltigeurs 5-2 [343, 344]. Sidney was able to bury the controversy behind him when, in March, he set a new record for the most points scored by a 16-year-old junior. He kept both the record-setting stick and puck from the game [332].

The Océanic secured a first-place finish in the Eastern Division by winning 4 of their last 7 games, earning a first-round bye in the playoffs with 34 regular season wins and 76 points [66, 344]. They faced the Shawinigan Cataractes in the quarterfinals, and during the second game, Sidney was sent out as part of a 3-player penalty kill on a 5-on-3 powerplay. He completed a hat trick during that kill. He had never scored a 3-on-5 goal before, and when he looked around for teammates to celebrate with, he found them all still on the other side of the ice [66].

“A kid that young shouldn’t even be on the ice in that situation. But Sidney brings skills and speed I’ve never seen in a 16-year-old.”

- Donald Dufresne, Rimouski Océanic Coach [66]

As impressive as Sidney was, Coach Dufresne was unwilling to make him the “load-bearing player” for the team. Dufresne made several adjustments during their series against Shawnigan and designated Marc-Antoine Pouliot as his “go-to guy.” Sidney was asked to follow Pouliot’s lead, and he told the media it was unfair to say the Océanic’s performance depended on a single player. “We play as a team, we win as a team, we lose as a team,” said Sidney [203].

“It might look [easy] by looking only at the scoresheet, but it’s tough hockey in the playoffs. You really have to work for your opportunities and your chances. It’s just a matter of making sure you’re focused when you get your chances and taking advantage of those. That’s what I’ve tried to do. The main thing is to get wins and it just so happens that my job [is] to help out offensively. And that’s what I’ve tried to do.” - Sidney Crosby [203]

The Océanic swept Shawnigan and moved on to the semifinals against the Moncton Wildcats, where the Océanic’s Memorial Cup dreams were vanquished. Moncton had a strong defense full of 19- and 20-year-olds and a good goaltender in Corey Crawford [203]. The Océanic was only able to win one game in the series before being eliminated. Sidney tallied 7 goals and 9 assists over his 9 playoff games [33].

Sidney’s first year in the Q had been, as expected, phenomenal. From his first regular season game—in which he scored a hat trick—to his impressive contributions in the playoffs, he’d delivered on the hype. He had been kept off the scoresheet only six times during the season, and scouts agreed that he left “two or three points on the ice most nights in Rimouski because his QMJHL teammates [couldn’t] play at his level” [35, 148, 328].

“Expectations were high for me and I tried to meet them by doing what I knew I could do.” - Sidney Crosby [332]

He accumulated 135 points (54 goals, 81 assists) in 59 games, leading the league in scoring to win the QMJHL’s and the CHL’s scoring titles [16, 35]. He was the QMJHL’s player of the week six times, the player of the month three times, and the CHL’s player of the week three times that season. He was also named to the CHL’s first all-star team [35, 280].

“To be honest, I’ve never sat down and said, ‘I want this record or that record.’ It’s a bonus if it happens. It means you’re doing well and helping your team. It doesn’t even cross my mind until it’s brought up. It’s best that way: you don’t gauge yourself on how other people have done. If you pass someone, great. If not, there’s a reason why it’s a record.” - Sidney Crosby [171]

At the QMJHL Golden Puck Awards—held on March 31, 2004, between the first and second rounds of the Q’s playoffs—Sidney took home 6 awards: the Michel Brière Memorial Trophy for Most Valuable Player, the RDS/JVC Trophy for Rookie of the Year, offensive player of the year, offensive rookie of the year, personality of the year, and the Jean Beliveau Trophy for league scoring leader. His 135 points were a league record for a 16-year-old. He was also the first player to ever win the Jean Béliveau Trophy, the RDS/JVC Trophy, and Michel Brière Memorial Trophy at the same time. “I’ll be back for sure,” said Sidney. “Rimouski is where I want to play. There’s no question about that” [14, 33, 177].

“It’s great. I wanted to make the adaptation to major junior as easy as possible and I was lucky to play on a good team and be in a great place. That helped me to play right away and do as well as possible.” - Sidney Crosby [177]

Though the Océanic was out of the running, Sidney was invited to watch the Memorial Cup as a guest. He was a nominee for the CHL’s Player of the Year award and became just as much of an attraction at the rink as the game itself. He was barely able to watch the ice because children lined up and asked him for autographs. Pat Brisson and Troy Crosby had to ask the kids to wait until the intermissions so Sidney could watch some hockey [46].

At the CHL’s awards ceremony on May 19, Sidney became the first 16-year-old to win the CHL Player of the Year award. He also won awards for the major junior top rookie, top scorer, and the Canada Post Cup, a new award given to the player who’d earned the most three-stars-of-the-game selections over the season. He was the first player to ever win player of the year, top rookie, and top scorer in the same year. “I know the kind of player I am,” Sidney said after the awards luncheon. “I know what I need to improve. And I know what I’m capable of. If I fulfill my own expectations, I know I’m doing my job” [136, 251, 280, 333, Taking the Game…, p. 137].