VII. RIMOUSKI II

Predictions for the Océanic’s season were optimistic.

The team’s staff and NHL scouts from across the continent were eager to see what Sidney had in store. What none of them were prepared for, Sidney least of all, was Sidney becoming the most famous 17-year-old hockey player in history [Most Valuable, p. 114-115].

After almost two years of failed collective bargaining talks, the NHL announced a lockout on September 16, 2004. The 2004-2005 season would be lost to the lockout, and the NHL would become the first North American major pro sports league to cancel an entire season because of labor disagreements. Aside from the AHL, juniors was now the highest level of hockey in North America [95, Most Valuable, p. 114-115].

In the gaping void left by the NHL, Sidney stood as a lightning rod for hockey news. National networks churned out daily updates on his performance, and any crumb of news about him became a “full-blown story” that was circulated from newspaper to newspaper [366]. If people had even a speck of knowledge about hockey, they knew who Sidney Crosby was. He’d already been profiled by ESPN and Sports Illustrated. “Even as young NHL all-stars, Orr and Gretzky remained hockey players; as a junior, Crosby had been fast-tracked toward something else entirely. He was a phenomenon, a commodity, a brand” [Taking the Game…, p. 138-139].

“It helps he’s North American. It helps he embodies the game’s core values. It helps he has his own brand of charisma. But the biggest thing about Crosby is he’s arrived when he’s needed most.” - Ed Willes, reporter [328]

Though the spotlight was on their star, the Océanic struggled in the first few months of the 2004-2005 season. Sidney nonetheless led the league in scoring, averaging 3 points per game while his team lost as many games as they won [Most Valuable, p. 119-120, Taking the Game…, p. 154].

October was a difficult month to weather. On October 1, the “worst moment of [Sidney’s] junior career” was inflicted on him by Frederik Cabana of the Halifax Mooseheads. In the first period of the Rimouski vs. Halifax game, Sidney skated across the blue line and was slammed by Cabana with a knee-on-knee hit that left him “writhing” on the ice. He had to be helped off by the Océanic’s athletic trainer, but before the trainer even stepped foot on the ice, Sidney was yelling at Cabana, who was a former teammate of Sidney’s from the U18 Junior World Cup [129, Taking the Game…, p. 147].

Sidney had been nowhere near the puck when Cabana hit him, and Sidney’s teammates took it upon themselves to enact vengeance. Several of them made runs at Cabana in the following minutes. Sidney returned in the second period and notched two points in the Océanic’s 4-2 loss, but all was not well. Though an MRI done after the game showed no ligament damage, his left knee faltered in the next few days. The team’s medical consultants determined that Sidney had bone bruising and he was unable to skate for 10 days after the hit. The Océanic didn’t expect him back in the lineup until October 15 at the very earliest [126, 128, 336, 337, Taking the Game…, p. 147-148, Most Valuable, p. 119].

Cabana was suspended for 8 games for the hit, drawing the attention of national media. Cabana’s billet family lived in Cole Harbour, and Cabana told reporters “People were so angry that I couldn't leave my billets’ house. The media were out on their lawn, waiting for me.” Not all the attention was critical of Cabana; some Halifax media turned on their native son, claiming that Sidney received special attention from QMJHL officials [Most Valuable, p. 119].

The local media wasn’t the only critic. The Mooseheads’ general manager, Marcel Patenaude, thought the 8-game suspension was an overreaction. Pointing to the measly 2-game suspension a Lewiston player had received for a bad hit on Cabana in September, Patenaude accused the Q’s officials of uneven standards, especially since Cabana had never been suspended before. QMJHL disciplinarian Maurice Filion stood by his assessment of the situation and upheld the suspension. Fillion also gave Océanic winger Alexander Vachon a 4-game suspension for hitting Petr Vrana while he was down on the ice a scant few minutes after the hit on Sidney occurred. Sidney’s linemate Dany Roussin would also serve a 1-game suspension during the Oceanic’s 8-7 loss (in overtime) on October 12 to the Quebec Remparts [128, 337].

The Océanic felt that the Cabana hit was the latest and worst example of the aggression Sidney faced on the ice [126]. Sidney’s billet housemate Neilson relished the opportunity to make use of his fighting skills—“I enjoy looking after my players and looking after myself,” he said. “The adrenaline rush when I fight, I enjoy that”—but Neilson alone wasn’t enough to stop other teams from trying to take Sidney down [204].

“[If someone abuses Sidney] I go, I put myself in front of them face to face. And I just... I talk to them, make sure... you know, give them a warning and stuff, and say ‘Look, you gotta let him play.’ And if they continue to [abuse him] then I’ve got to drop the gloves and try to correct what they’re doing wrong.” - Eric Neilson [204]

The physical punishment Sidney took each game was extraordinary. “[Opposing players] beat him, they chopped him, they did everything to him,” said one of Sidney’s representatives, Dee Rizzo. “They cross-checked him from behind, they slashed him in the face and he never whined about it” [238]. Some media members even argued that Sidney should jump to a pro league in Europe, where it would be less likely some NHL hopeful would try to make a name for himself by landing a serious hit on Sidney Crosby [299].

Tragedy struck later that month. Kenny Schrum, Linda Crosby’s common-law partner for more than 20 years, passed away. The London Free Press reported that Schrum suffered a heart attack on October 28 and passed away on October 31st, hours before Sidney was set to take the ice in Moncton. According to the paper, Troy told Sidney of his grandfather’s passing after the game and Sidney broke down in the locker room. It was the first time he’d experienced the death of a loved one. When the team spokesperson proposed sneaking out the back door to avoid fans, Sidney refused. “He wiped his face dry and went to sign autographs. He asked only one consideration. Please no photos. His eyes were blood red” [60, 126, 377].

“Nothing can prepare you. You just have to go through it.”

- Troy Crosby [126]

This story was corroborated by ESPN and The Ottawa Sun, in which they described the 100-or-so kids who had waited outside the barricade at the Moncton Arena, watching the locker room’s door for a glimpse of Sidney. “I was pretty shook up,” said Sidney. “But we only get to Moncton a couple of times and I knew I wouldn’t get a second chance to sign for those kids” [14, 126, 127].

The Halifax Daily News, however, reported that Sidney had been informed of Schrum’s death on November 1 before his game against the P.E.I. Rocket at the Charlottetown Civic Centre. The Océanic had blown a 4-2 lead to lose 6-4 to the home team, and Sidney admitted he had considered not playing in the game and carried a heavy mental load on the ice. He’d ultimately chosen to compete, knowing that fans on Prince Edward Island wanted to see him play. His single tally for the night was an assist, and immediately after the game he left for Cole Harbour [276].

The Halifax Chronicle Herald had yet another account of the events: according to a quote from Troy Crosby, Schrum had died while Troy attended an Océanic game in Cape Breton on October 29. Near the end of the game, Trina called Troy with the news, and after the game Troy met Sidney, freshly out of his gear and covered in sweat, and told him [365, 378].

“He took it pretty hard and he was crying and there were a lot of people around. I don’t know if people thought I was yelling at him or something because he was pretty upset. But people were walking by and he was out there for a long time before he showered and got dressed. It was about an hour later and [Océanic Director of Hockey Operations Yannick Dumais] told him he could just go back to the hotel and not worry about signing autographs or anything. But there were a lot of people still waiting there, even after an hour, and he said, ‘No, I want to do it, but no photos,’ because his eyes were pretty red.

“That’s something that shows you he understands that it’s important to those people because he knows he was in their shoes just a few years ago waiting for autographs. He just thought that was important, even at a time like that.” - Troy Crosby [365]

Schrum’s obituary lists his death date as October 29, 2004, which would seemingly validate Troy’s account in the Chronicle Herald. Though the available information differs, the facts that can be confirmed are that Sidney played in Cape Breton, Moncton, and P.E.I. (all losses: 5-3, 9-5, and 6-4 respectively) and took two days to attend services in honor of his grandfather. It would not be the only personal loss he experienced that season. Earlier that summer Linda was diagnosed with cancer and hospitalized for eight months. Sidney’s great-grandmother also passed away around this time. “People only see the pictures and the smiling young face,” said Troy, “but Sidney understands about life” [60, 377, 378].

Hockey remained a stalwart constant for Sidney. By November 9 he had notched 15 goals and 31 assists in 20 games. While the NHL weathered scorn from its fans during the lockout, the QMJHL savored Sidney’s talent and media profile. “For sure, there’s a lot of attention on him,” said Yannick Dumais, the Océanic’s director of hockey operations and the man responsible for dealing with media requests about Sidney. “Right now, he’s the biggest name in hockey” [306].

The Q’s attendance had risen by 8% and when the Océanic came to town, the arenas filled up. “At the age of 16, [Sidney] created more media attention than anyone else, for sure,” said Gilles Courteau, the QMJHL’s commissioner. “Mario was great at 16, but today, because of the media attention, he’s so much bigger than Mario was” [306].

Wherever he went, whatever arena he played in, fans packed the stands to see him. His mere presence was worth a projected $1 million to Quebec league owners that season. When the Océanic was on the schedule, that number jumped even higher. The Océanic was the most popular team on the road, often playing to crowds as large as 90% capacity for arenas. The second most popular team (the Chicoutimi Saguenéens) played to 65.9% [14]. In Quebec City, Sidney drew over 14,000 fans to a game. The Drummondville Voltiguers attempted to move a game against the Océanic “from their 3,000-seat rink to the 21,000-seat Bell Centre in Montreal” [42].

To bolster profits, teams began packaging tickets; to see an Océanic game, a fan would have to buy another ticket to a game featuring other teams. The ticket packages averaged around $40 for 3 games [14].

With owners making a pretty penny off him, Sidney realized that the hiked ticket prices meant some fans would not be able to afford to see him play. When he was younger, he’d always wanted to see Vincent Lecavalier and Brad Richards play when the Océanic came to town. It would have been difficult for the Crosby family to afford the $40 packages [14].

Sidney and Pat Brisson “requested that 100 tickets for each Océanic game be distributed to underprivileged kids. Some club executives resisted.” In the end, only 25 tickets were made available for each game [14].

“My personal opinion is 25 is far less than it should be. There was some grumbling, but I’d say those who criticize it are the greedy ones. Sidney didn’t want anything out of this for himself. He just wants underprivileged kids to have a chance to see him play. It’s not fair and we were upset.

“Some GMs and governors... they’re lucky to have [Sidney] in their building three or four times. They should have been happy and just gone along with it.” - Pat Brisson [14]

Sidney was pulling significant weight in the league, from the sales he brought in to the power he commanded in negotiations with league management. Still, Sidney was modest in front of the media, always crediting the whole team for their wins [306].

“It’s pretty much the same as last year. All the places we go are pretty much sold out, and other teams are motivated for that. That’s a challenge, for sure. It takes more than one guy to win, I’ve always realized that. You win as a team and you lose as a team, but there is a little bit of extra pressure [on me]. That comes along with it. When you’re expected to score points, the expectations are high.” - Sidney Crosby [306]

His fearlessness, his strength on his skates, his hockey IQ, and even his quality of being “shifty” were on full display [19]. The NHL was paying attention:

“He’s a unique player who makes plays at both ends of the rink. Coming up-ice, most players, even the great ones, try to get to their favorite areas so they can make plays. You usually know where they’re going. They’re still tough to stop, but at least they’re predictable. Crosby isn’t. He plays both sides of the rink and is able to feed both sides.”

- Tim Burke, San Jose Sharks Director of Amateur Scouting [19]

“Every talent that you need to be a hockey player, this youngster’s got it.”

- Frank Bonello, Director of NHL Central Scouting [20, 0:53]

“He’s going to be a star. Sometimes he’ll make a play and you’ll think it’s the wrong one, then it strikes you that the guys he’s out there with are not thinking on the same high level as he is. We need another Canadian superstar. They’re hard to find.”

- Kevin Prendergast, Edmonton Oilers Vice President of Hockey Operations [19]

“His poise is natural, it’s not an act. I’ve heard people call him cocky, but he’s not cocky at all. He’s confident in his abilities. And like all great players, he understands his place in the game. Good players know how good they are. People tend to forget he’s only 17 years old.”

- Blair Mackasey, Hockey Canada head scout [334]

When asked about his goals for the season—was he seeking a Memorial Cup win? Did he have any thoughts about his future in the NHL, if there would be an NHL?—he deflected the questions with a mature confidence beyond his years. The attention was a double-edged sword; it wasn’t only the media who saw how good he was. Rival coaches were tailoring their teams and gameplay to obstruct Sidney as best as they could. The Cabana hit was not an isolated incident. “He was prepared for that; we talked about that in the summer,” said Pat Brisson. “He thought the second year might be more difficult, that teams were going to be ready for him even more. Teams put a guy on him the entire game, but again, he knew that was going to happen” [306].

And happen it did. Sidney had put in work to develop his defensive skills over the summer and earned consistent ice time on the Océanic’s penalty kill as a result [14]. He’d also added an inch and 18 pounds onto his frame, making it easier for him to stand against the physicality he encountered. “I know what to expect when I get on the ice,” he said. “I’m always playing against the best defensive players, but that makes me a better player” [152].

“Sidney doesn’t shy away from the traffic and he’s become a major target. Before each game, the game plan is to stop Sidney Crosby, so you see a double effort from each team when they play against him. But he can’t be careful. He goes to the net if he has to. We just hope the league continues to call the penalties. Then he should be fine.” - Pat Brisson [158]

His added strength and mass meant he was even chippier in the corners. In the second period of the November 13 game against the Gatineau Olympiques, Sidney caught Gatineau winger Francis Wathier with his head down, landing a hip check on Wathier that sent the large player to the ice right in front of the Gatineau bench. The Olympiques protested, and a scrum snowballed into a fight between Gatineau’s Nick Fugère and Rimouski’s Erick Tremblay. As Sidney picked up gloves and sticks in the aftermath, the Gatineau bench chirped him over the hit. Sidney looked at the bench and tapped the bottom of his chin with his glove. “I hit Wathier with his head down and he got all mad,” he said. “He would have done the exact same thing, so I was just saying that he should keep his head up” [14, 317].

“You give him an inch, he’ll take it and he’ll hurt you with it.” - Benoit Groulx, Gatineau Olympiques coach [317]

People traveled to watch him play—“We saw him play in Charlottetown when he was 10 years old, and he scored three times in that game. We heard he’s an up and coming Wayne Gretzky, and we’re just hoping to see him score a goal” said Cole Harbour resident Dorothy Akitt, who had made the trek to see Sidney play, squeezing into the Gatineau arena with standing-room-only tickets. Locals had gobbled up the rest. “I just wanted to see him play. I’ve heard a lot of good things about him, and I just wanted to see how he plays,” said local child Andrew Langlois. “I think it’s really good that he comes from a small town, and it shows that he works really hard” [316].

Sidney’s superstar status got him an invite to the 2004 ADT Canada–Russia Challenge, the same competition he’d participated in the previous season. “I’m looking forward to these games because any time you face a Russian team, it’s exciting,” he said. “There’s so much history to the rivalry between Canada and Russia. In recent years, there’s been a growing rivalry with the U.S. and with the Olympics, the World Cup and the World Juniors, but these games are special.” Though Sidney noted that neither Alexander Ovechkin nor Evgeni Malkin, the top two picks in the 2004 NHL Draft, would be participating, he was still excited to compete [152].

His hopes would be dashed. The QMJHL knew Sidney would be on the roster for Team Canada at the 2005 World Juniors tournament. In anticipation of the games Sidney would miss while competing, the Q had loaded the Océanic with 11 games in 17 days in November, desperate to squeeze every cent out of Sidney’s presence even though it put him at significant risk for burnout and injury [Taking the Game…, p. 154].

Sure enough, on November 19, three days before the Canada-Russia Challenge, Sidney tripped and fell awkwardly on his ankle while playing against the Quebec Remparts. Though he finished the game, the injury worsened after he played against the Cape Breton Screaming Eagles the following night [157].

“It’s swollen. It needs time to heal,” said Sidney. “I don’t want it dragging on all season. It’s too important of a year. I could barely finish the game, so I was thinking what’s going to happen in the next couple of days? It was getting worse so I had to take a break to see how it went.” Ultimately, Sidney ended up pulling out of both Canada-Russia games [158].

His absence had a visible impact on walk-up ticket sales for the first game, and organizers anticipated even fewer attendees for the second. Although Sidney wouldn’t be playing, he and Pat Brisson flew to Montreal for the games anyway, both to watch the competition and to run the media gauntlet. “I just wanted to come up and support the guys and be a part of this,” said Sidney [158].

At a press conference to introduce the QMJHL selects, held at the St. Hubert restaurant next to the Bell Centre, Sidney courted the media perfectly. Though he arrived late from the airport, he looked “freshly scrubbed” and pocketed his cellphone in his dark pinstriped suit with its open-collared white dress shirt. He charmed the media with his incongruous athletic gait and “adolescent high-pitched voice.” Pat Brisson told the scrum that Sidney was “the full package... for the entertainment business.” He was right. All of Sidney’s soundbites were squeaky-clean, even in the face of the notorious Montreal media. When TSN’s Michael Whelan questioned Sidney’s injury—“You’re not even on crutches, c’mon?”—Sidney “looked up, his eyes twinkled and he caught himself before he smiled too broadly” [334].

The media had been eager to see Sidney in the national spotlight again. With Sidney out of the lineup for the Canada-Russia series, the next shot he’d have at nationwide glory was at World Juniors in December and the Top Prospects game in January. Sidney reaffirmed his desire to win gold for Team Canada and graciously told reporters he wouldn’t mind being coached by Don Cherry, who had been named a coach for the Top Prospects game [158].

Well, somewhat graciously. “It doesn’t matter. I’ll go for one game and whatever happens, happens,” he said [158].

That was his general attitude toward the future. He deflected questions about the NHL and his jeopardized draft. “I play hockey,” he said. “I don’t decide if there’s a draft or not. Hopefully they’ll take care of it, but it’s out of my control. All I can do is have the best season possible and see what happens” [158, 334].

His absence was felt in the games, both shootout losses for Canada [334]. He’d have his chance to face the Russians in a matter of months, but it was time to head back to Rimouski.

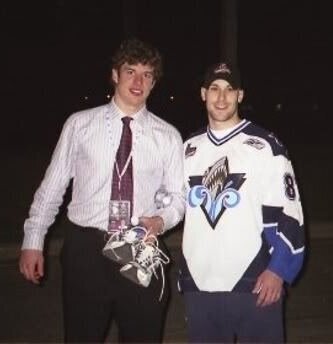

Things were going well off the ice for Sidney in Rimouski. It was reported that he was being paid around $30,000 by the Océanic, which was unprecedented in junior hockey [15]. Some theorized Tanguay could be paying Sidney north of $100,000 [Taking the Game…, p. 182]. He didn’t need to have Neilson drive him around anymore because he had his own Mazda SUV and a learner’s permit [49, 50]. His black-and-orange beaded necklace had broken and been replaced with the light and dark blues of the Océanic—two white beads on the string had the numbers 8 and 7 printed on them [338].

He was an honors student at Harrison Trimbele High School, sinking five hours a day into private tutoring [23, 126]. With the help of a team counselor, he would graduate on schedule. “I’ve put too much into school,” he said. “It would be stupid for me to put in all of this work and then quit now” [72].

His mounting fame meant that he wasn’t like most other high school seniors; Sidney would have to sneak out of auditoriums with PR staff, and when Troy came to visit and have breakfast with his son in a hotel restaurant, fans swarmed their table. A reality TV show asked to follow him around for two days, though he denied the request [20, 8:43, 72].

“It gets pretty crazy. It’s like The Beatles. He has to have security. There are two or three guys who help him, an usher and rink workers. He has to go out the back steps. My wife [Trina] got pretty upset… But [Sidney] knows this is part of it.” - Troy Crosby [72]

“…sometimes people come up and they ask for an autograph, and they think they’re the only one. The thing they don’t understand is that he’s gone to a practice. He’s done five interviews, and then after he’s done that he’s spent an hour signing stuff for charities. And then he goes home and has a bite to eat before he has his tutoring or before he does his schoolwork, and then he may be on the phone, or be on MSN (instant messenger) to [talk] with his family, or friends. So we’re not complaining about it, at all. It’s just the way things are today.” - Trina Crosby [46]

His media presence was becoming more and more developed. The media flattered him with descriptions such as the “center with the tousled black hair and half-smile.” He wore dress shirts and ties to the rink “because he [remembered] New York Rangers general manager Glen Sather saying that if you dress well, you play well.” He met daily interviews with an engaged but polite air, and was kept on schedule by Yannick Dumais [46]. He smiled reflexively when answering questions; some called him “the most camera-warm hockey star since Orr.” He had an unusual comfort with how the media dug into his life. “It gets to be part of your routine,” he said, “like putting your equipment on before practice” [50]. Journalists divulged that IMG (his agency) had given him media-training classes over the last two summers [19]. Troy Crosby disputed the reports.

“You want your children to be respectful and have good values and stand by what you believe in. He never had any formal training in terms of dealing with the media. When I read that, I get a little insulted. He wasn’t sent to acting school. We believe in treating people the way you want to be treated. We’re really proud of him, the way he has handled himself from a very young age.” - Troy Crosby [65]

Sidney endeared himself to the francophone media when he started speaking French during interviews. Some were impressed with how fast he learned the language and how he continued practicing it [The Rookie, p. 200]. He bribed himself with incentives; if he made the World Juniors team, dinners at his billet home would be French-only [44].

“I thought it was the right thing to do in a place where everyone was French. I kind of spoke a little, a word here and there my first year. But by my second year, one night instead of doing my post-game interview in English, when he asked me the question in English, I answered in French. Everyone was kind of surprised, but after that I would always do my interviews in French.” - Sidney Crosby [The Rookie, p. 200]

“They assumed I would do just English. I knew that I was able to respond in French, so for people listening, I thought it would be nice to respond in French because a lot of people don’t understand that much English.” - Sidney Crosby [44]

Sidney had taken note of his privilege as an English speaker; “As an English person going there, you realize how hard it is for people... to try to speak English for you,” he said. Locals would still try to speak English to anglophones, but Sidney realized that in English-speaking provinces, francophones were rarely afforded the same courtesy [318].

“I try to do my best to learn the language. It’s only good that can come out of that, so I try my best to pick it up. I’m not perfectly bilingual, but I understand pretty much everything. I’m starting to talk more and more as I’m there. Hopefully I’ll be pretty close by the end of the year.” - Sidney Crosby [318]

His efforts to speak the language impressed locals, and stories erupted of Sidney and his teammates showing up around town to play pickup games at outdoor rinks. Sidney, just like when he played street hockey with his friends in Cole Harbour, was relegated to goalie. One Rimouskois had a story about Sidney stopping during a jog and helping dig a car out of some snow [44].

“He is so respectful. When you see the effort he has made to speak French, you can’t not think he’s great.” - Suzanne Tremblay, season-ticket holder and former Bloc Québécois MP [44]

Sidney still loved hockey more than anything; he called home to ask his parents to send over spare skates when the Océanic trainers hid his skates so he would obey the team’s rest days. His parents helped him out, but Sidney was caught by one of his coaches on an outdoor rink [49]. He was relentless in his training, usually 45 minutes early for each practice. Five days a week, he spent 90 minutes at a gym run by Claude Bellavance [50].

Bellavance would practice his English with Sidney during workouts and was blown away by Sidney’s fervor. “When I met Sidney for the first time,” he said, “I could not get over how intense his eyes were—they had fire in them.” He wasn’t the only one impressed by Sidney at his gym. When Sidney had to take off his shirt for a physical evaluation, Bellavance claimed women in the gym abandoned their workouts to take a look. “I was sort of surprised,” he said. “I mean, some of these women were well over 60” [44].

“He doesn’t drink any pop, doesn’t eat sugary stuff, doesn’t stay out late, doesn’t have time for a girlfriend. He wants to win so bad he can’t even play a game of cards for fun.”

- Guy Boucher, Rimouski Océanic assistant coach [50]

His dedication was infectious. “The players will tell you that he is a model and that they were trying to follow him. Not only for his talents as a hockey player, but also because of his personality,” said Doris Labonté, the Océanic’s general manager. “He did not allow himself to relax, and he did not accept it from the others. He had a goal and he knew what to do to achieve it” [321].

“He was always the first on the ice during practice and the last to leave. There was no choice but to follow him. He's a great leader. He wasn't the most talkative in the locker room, but on the ice he was setting an example for everyone.” - Patrick Coulombe, Océanic teammate [321]

That wasn’t to say Sidney’s teammates never had any complaints about him. His superstitions started to become the talk of the media while he was with the Océanic. As his sister Taylor recounted:

“It all started when he was playing junior. He talked to me before a game and then he separated his shoulder. He tried to break the curse once and called my mom. She was like, ‘Should we be talking?’ and he was like, ‘Yeah, it’s fine.’ Then, that game, he broke his foot.” - Taylor Crosby [3]

Labonté admitted that Sidney’s superstitions could become “tiresome.” Sidney would sometimes inflict them on others—if they ate at a certain restaurant in a certain city, or if Labonté sat at a certain chair, or wore a certain tie, it was all fair game to become ritualized. “I don’t think he really believed in it,” said Labonté, “but it was his way of having fun, of relaxing.” The worst superstition of all was the Nordiques baseball cap Sidney wore. “It was dirty, beaten up, but he kept putting it on and we kept winning,” said Labonté. He also admitted that they hid it on occasion, but not often; when Sidney got angry, he got angry [321].

“I put on the equipment on my right side first. I don’t let anyone usually touch my stick after it’s been taped for a game, either. I don’t get too out of control; if you’re too serious about it, you will drive yourself nuts.” - Sidney Crosby [31]

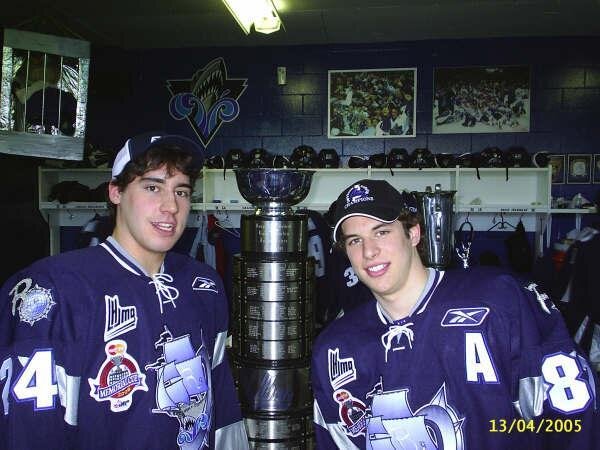

Winter came quickly, and with it came levity before the approaching storm of playoffs; Océanic coach Donald Dufrense annually built an outdoor rink at his home, and it was an endless source of amusement for the team. Sidney and his teammates would play shinny for hours, competing for a replica Stanley Cup that Sidney made using a garbage can and bowl he’d duct taped together. The winners’ names were added with a label maker. Who won? “I did,” he giggled. “I always do” [The Rookie, p. 250].

The frivolity wouldn’t last forever. Random trade rumors circulated, claiming Sidney was going to be traded to the Moncton Wildcats for Brad Marchand and a handful of rookies, or alternatively for Steve Bernier and Corey Crawford. Most newspapers in Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia refused to print the stories, as the sources were—at best—of dubious quality [300].

Then the Océanic suffered a seven-game losing streak, and in early December Labonté, “believing Dufresne was too nice and not getting enough out of the players,” pulled the same trump card he’d pulled in 2000: he demoted Dufresne to an assistant and took over coaching duties. That exact stunt had helped the Océanic win the Memorial Cup five years prior [233, Taking the Game…, p. 154].

While he was at it, Labonté shifted Sidney from center to wing, putting him on a line with Marc-Antoine Pouliot and Dany Roussin. “It’s a little different, but once we’re past the other team’s line, we can pretty much go wherever we want,” said Sidney. “I’ve played on the wing a little bit before so it wasn’t totally new” [292].

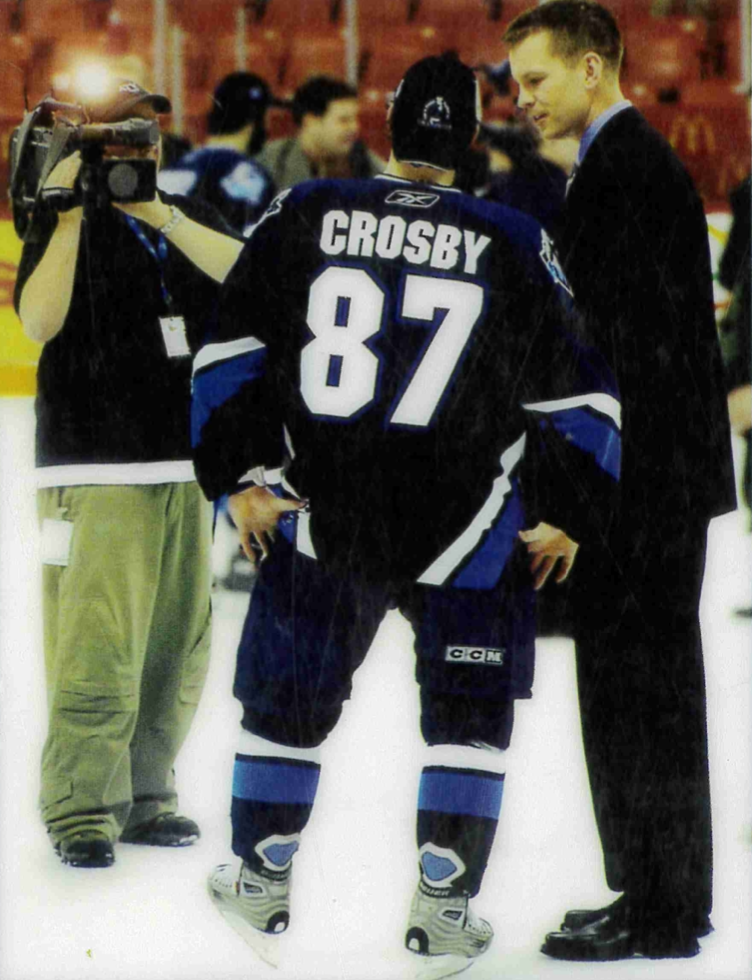

He was about to get even more experience as a winger on Team Canada. On December 13, Sidney hurried into the locker room at the MTS Centre in Winnipeg and was immediately barraged with chirps from his potential teammates. He’d missed the opening practice of the Team Canada Selection Camp the day prior thanks to a snowstorm that caught him at the Mont-Joli airport in Quebec [64, 178].

Though he was a veteran of the Canadian World Juniors team, he was still the youngest player in the room. “All the guys from last year for sure were giving me a hard time,” he told reporters after his first skate in Winnipeg. “I was thinking about that on the plane, that the next morning would be rough. It’s all in fun. For sure we crack some jokes in the dressing room.” His teammates also gave him the gears for being the only player at camp to wear a full face mask. As per IIHF rules, underage players are obligated to wear them, though Sidney didn’t like how it branded him as a younger player. “As soon as I put it on this morning, [I got] a few comments,” he said [165].

Over 30 reporters and camera crews laid in wait for Sidney after his first workout at the camp. Sidney dealt with the crowd in his usual practiced demeanor, shrugging off suggestions that the attention was overwhelming. “I’ve learned to deal with it,” he insisted. “After you’ve experienced it a little bit you learn to deal with it when the time comes. But my main focus is on playing hockey” [178]. The country expected great things from Sidney. “It’s part of being Canadian,” he said. “That comes along with it. Everyone wants to play on this team, no matter if there’s pressure, no pressure. This is the team to play on and you want to be there for sure” [178].

Due to the lockout, World Juniors was more than a Christmas tradition; it was a replacement Stanley Cup Final. The Canadian team was stacked and “passed for a reasonable facsimile of, say, the Detroit Red Wings” [Taking the Game…, p. 156]. The expectations of them could not have been higher.

“I know what I’m capable of doing. I expect the best out of myself and for me that’s not a lot to ask.” - Sidney Crosby [356]

32 players were present at the camp, competing for the 22 spots available on the roster. Only 2 goalies, 7 defensemen, and 13 forwards would be accepted onto the team. Team Canada’s coach, Brent Sutter, used a more professional camp format; instead of the cuts being announced every morning (which Sidney had woken up at the crack of dawn daily to hear the previous year), the roster would be announced in its entirety on the last day of camp, December 16 [350]. Morning cuts were considered a kindness; if a player was cut, he’d leave camp as quickly as possible so the camp’s atmosphere remained positive. Sutter had no desire to coddle his players. “If your team is that mentally weak you’re not going to win at the end of the day anyway,” he said. “I want to treat these guys like pros” [180].

Sutter was an intense coach. In selecting his team he was spoiled with options; the NHL lockout meant his talent pool was deep, though he didn’t want any players to rest on their laurels. He wasn’t just looking for the most highly-skilled players. He wanted the kind of drive that had led to fights at the summer evaluations. He wanted a real team. He wanted a pack. “At the end of the day,” he said, “we aren’t taking 22 all-stars, we are taking the 22 guys who we think can best form a team” [350].

“Obviously we are a team with a lot of skill and you want to go after your opposition, that’s my make-up. We want a pack-of-wolves mentality, that’s how we want to play.” - Brent Sutter, Team Canada head coach [350]

Sidney flourished under Sutter’s coaching style. “He’s a really tough coach,” said Sidney. “He doesn’t ask for anything but hard work and your best. It’s the perfect way to be. He’s always demanding, and you bring your best to the rink, no matter if it’s a practice or a game” [268]. Sutter was pleased with Sidney’s performance, but kept his comments about Sidney grounded. “Is Sidney Crosby a great player? Yes,” said Sutter. “But you expect him to be. He’s a year older. He’s a year more experienced. Let’s not forget he’s still 17. There’s a lot of elite players here and you expect everyone to play to their potential. Whatever role Sidney plays, he’ll play and I’m sure very well” [165].

On his first day at camp, Sidney was paired with centerman Patrice Bergeron. Also assigned as his roommate, Bergeron took on an older brother role for Sidney, who enjoyed the partnership immensely and constantly asked Bergeron questions about his experience in the NHL, AHL, and the IIHF World Championship, where Bergeron had won gold in 2004. Bergeron insisted they had more similarities than differences. “We’re both teenagers,” said Bergeron. “There’s not a big difference between 17 and 19 years old. We talk a lot about the NHL. I’m trying to tell him as much about it as I can” [135].

The two had a good rapport and poked fun at each other. “Even if he wasn’t a prodigy,” Bergeron drawled, “obviously he’d still be a 17-year-old guy and my roommate and I’d be helping him in the same way” [135]. Sidney, meanwhile, chirped Bergeron about his sleeping habits to the media— “He sleeps all the time,” Sidney said. “Whenever he’s got a spare moment he’s like, ‘let’s go sleep’” [188, 324, 356].

“He’s a great roommate. I’m trying to learn a lot, getting to know him and learn his tendencies. Just talking to him I’ve learned some new things about him and we seem to be able to click pretty well out there.” - Sidney Crosby [188]

Sutter saw Sidney and Bergeron’s puck handling and communication skills and knew they’d be a good hockey fit. Over the course of the selection camp, they emerged as Team Canada’s top line, playing with wingers Jeremy Colliton and Corey Perry. “It’s hard to explain. We feed off each other so well,” said Sidney. “We are finding each other out there and it’s a lot of fun to play with him. We are making good things happen. Colliton is doing a good job out there too, pushing the D back with his forechecking. We are making each other’s jobs easier and everyone is playing their role” [217].

“Sidney has such great vision on the ice, he sees everybody everywhere... It’s pretty easy to play with him, I just have to get open.” - Patrice Bergeron [217]

Sidney was “the most exciting player to watch through the pre-tournament exhibition games” by far; whenever he had the puck, people expected him to do magic. He seemed to have a “sixth sense” about where the puck would be, and when he got it on his stick, he was dangerous—even “on his knees.” He was “almost impossible to knock off the puck” and scraped and clawed for every point he could score. He was determined to prove himself at what he considered to be the highest level of hockey available to him. To Sidney, World Juniors was “such a higher level than junior. It’s a whole new step” [172, 202, 356].

“Oh yeah, he is better. He dominated last year, but this year he is even more dominant. He is quicker and stronger. But the thing I noticed that makes him so difficult to play against is he never makes the same move twice.” - Stephen Dixon, Team Canada teammate [338]

Even while holding his own at camp, Sidney wasn’t the loudest voice in the locker room. “It’s just not my personality,” he said. “I’ll talk once in a while about plays, but I’m not a screamer or a yeller. I’m not someone who is going to talk too much, but just try to lead by example on the ice” [165].

Screaming and yelling wouldn’t be necessary. By the time Team Canada scrimmaged against the University of Manitoba on December 14 and 15, Sidney had been scratched from the lineup along with several other players. They’d already made the cut [180, 234].

After the selection camp concluded and the roster had been set, the newly-formed Team Canada put on an exhibition series at the MTS Centre against Finland’s and Switzerland’s teams. Canada wore replica vintage jerseys from the 1920 Winnipeg Falcons—who won Canada’s first Olympic gold medal—during their game against Finland, which they won decisively (6-0). Sidney notched a goal and two assists in the game. His goal, the game’s first, was on a power play, and one of his assists was a beauty of a pass to Bergeron as Sidney stepped out of the penalty box [187, 217, 234].

The 2005 World Junior Ice Hockey Championships were held at the two Ralph Engelstad Arenas in Grand Forks, North Dakota, and Thief River Falls, Minnesota from December 25, 2004 to January 4, 2005 [100]. It would be the third year Sidney spent Christmas away from Cole Harbour [The Rookie, p. 171]. Troy would travel to Grand Forks for the first game of the tournament, held on Christmas Day. Trina and Taylor would follow a few days later. “I’m so excited,” Trina said. “This is what Christmas has always been for us. We always planned the days around watching the games. It was always his dream to actually be there. And now he is. This is almost like when he was a little kid. Only now, he’s playing” [49].

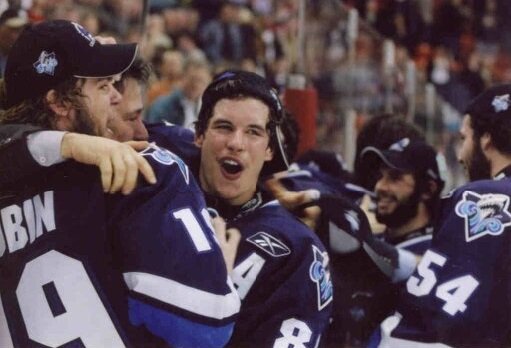

From the moment Team Canada stepped onto the ice, they took the reins of the tournament and didn’t let go. Sidney was playing with what some would consider the “greatest World Junior team of all-time.” Bolstered by the lockout, fed by an amazing draft class, and hungry for redemption after the 2004 silver medal, the Canadian World Junior team was poised to end their seven-year gold medal drought [6]. The lineup featured Patrice Bergeron, Jeff Carter, Ryan Getzlaf, Shea Weber, and Dion Phaneuf, among others [99].

“We were so focused during the tournament, I don’t think we really realized how good we were. With the lockout, we had our own guys back, but there were a lot of other guys on other teams that were pretty capable of changing a game with one play... After it was all said and done, and you looked at each game and how we played and how we carried the play, it was pretty impressive. When I look back, I definitely think it was one the best teams I ever played on.” - Sidney Crosby [6]

In their first game on December 25, Bergeron and Sidney’s chemistry awarded them with two goals apiece (and two assists for Bergeron, one for Sidney) in a dominant 7-3 win against Slovakia [135].

They knew they could do better. The media knew they could do better. The Canadian team was extraordinarily good, to the point where they were criticized for letting Slovakia “back into the game” at all. Sidney agreed. “We played good, but we can play better I think,” he said. “We’ll kind of set our standard there and try and get better as the tournament goes on.” Sidney looked at the tournament as a “second chance” at redemption after the 2004 loss. He was “obsessed with winning, obsessed with succeeding,” said Team Canada Assistant Coach Jim Hulton [64, 135, 176].

“To be here once before you’re lucky, but to get a second chance, you want to get advantage of it. For sure you don’t want to let it slip away.” - Sidney Crosby [202]

“This is the team to play on and you want to win the gold medal; anything else isn’t acceptable.”

- Sidney Crosby [215]

It only took a day for Sidney to make a critical misstep, but it was a fumble in front of the media instead of on the ice. On December 26, during a live interview with TSN, reporter Gino Reda asked Sidney if he would consider being a replacement player in the NHL. What was being asked, effectively, was if Sidney would be a scab for the NHL in their labor dispute with the players’ union [Taking the Game…, p. 157].

It was not the first time the question had been asked. Pat Brisson had already rebuked the idea to the press in previous interviews. Yet, on national television, microphone to his lips, Sidney said “I haven’t really given it a lot of thought but my dream is to play in the NHL. I think, if I do have an opportunity, I would probably go” [138].

Wrong answer, Sidney.

“CROSSING THE LINE?” wrote one newspaper. “Junior hockey phenom Sidney Crosby is toying with the idea of being a replacement player next season if the lockout drags on.” Others followed. It was bombshell news; the NHL’s most hyped prospect of all time was offering to dive past the players’ association and play for the league in the middle of a strike [138].

Or, at least, that’s what it had sounded like. As it turns out, most 17-year-olds don’t have a “command of macro- or micro-economic issues.” The next day, a “visibly shaken” Sidney asked TSN for the chance to explain himself. He said that he’d thought Reda had asked if Sidney would be a NHL player if the NHL players returned to play, not be a replacement player. “I understand what’s going on a little bit but not fully,” Sidney insisted. “I try to understand as much as I can” [Taking the Game…, p. 158-59].

“It was just a misunderstanding. I didn’t understand the question. I responded by saying that I’d play and it was just a big mess-up,” Sidney clarified. “I want to play in the best league in the world and the NHL isn’t the NHL without NHL players, so for sure, no, I don’t think I’d be there” [207].

His media catastrophe put to rest, Sidney and Team Canada breezed through the preliminary round with a perfect 4-0 record and earned a bye to the semifinals. By the end of the first round, they outscored opponents 32-5 and Sidney had accumulated 6 goals and 7 points (though he had been held off the scoresheet during Canada’s 8-1 win over Finland). In the second game against Sweden (8-1), Swede Robert Nilsson brutally slashed Sidney’s wrists, but Sidney didn’t miss a shift and went on to score two power play goals [191].

The veterans from the 2004 team were impressed by how much Sidney had developed since the last tournament. “Sidney was so much stronger on the puck. It was unbelievable the difference in his strength,” said Team Canada captain Mike Richards. “And he was a lot more aware of what was happening on the ice. He had a better understanding of what it was going to take for us to win. It was like a carry-over from Finland... On the ice and off the ice we picked up where we left off the year before” [268, Taking the Game…, p. 164].

“It’s a different atmosphere this year. We don’t have that happy-to-be-here mentality. We know we’re here for a reason. It’s four games in, but the hardest hockey is still ahead. We’ve got to make sure that we’re prepared for this next game.” - Sidney Crosby [268]

The media drew in closer. Slightly Crosby-weary from the nonstop Crosby updates that had filled the Canadian news cycle, they started to pick at Sidney’s performance. Though Sidney was doing well, he began to lack offensive opportunities. “Canada’s mantra at this tournament [was] defense first,” and Sutter locked down his defensive system, adamant that Canada had its best shot at gold by playing a defense-heavy game [202, 351].

As his chances to be flashy and bombastic fizzled out, the rest of Team Canada’s fantastic roster rose to the challenge. “The team was so good that the best competition it faced was against itself in practices” [185]. Sidney’s impact on the team wasn’t a standout performance, and he instead became a very good part of a fearsome whole [Taking the Game…, p. 160].

“...I think we’ll look back on this team and say, ‘That team was so good that the kids all played up at Crosby’s level.’” - Lorne Davis, Edmonton Oilers scout [Taking the Game…, p. 165]

The media had billed World Juniors as Sidney’s “star vehicle, his personal showcase, his stage.” When he wasn’t able to do cartwheels on the ice, some began to claim that he wasn’t living up to the hype. “He was okay,” said an NHL scout. “He was good. Just don’t make it seem like he tore the place up. He didn’t dominate” [Taking the Game…, p. 160-161].

In the face of the criticism, Sidney kept his head down and got to work. He was still a generational talent, still a 17-year-old holding his own against 19-year-olds [328]. Thinking he was in private, he would do flashy tricks (like his “lacrosse move”) during practice freely. When footage of his playfulness leaked and he got in trouble for it on Coach’s Corner with good ol’ Don Cherry, Sidney locked it down and wouldn’t do anything fancy or too creative when he knew he was being watched [6].

“We need him. We’re in the entertainment business and we need more players like him. We need some good stories.” - Vaughn Karpan, Phoenix Coyotes Director of Scouting [328]

Sidney’s deftness in the face of all the media attention impressed his teammates. “He’s comfortable with it,” said Bergeron. “He’s like that. He’s a laid-back guy. He takes it day by day and he can let things go and just play his game and enjoy what he likes the most” [125].

Sidney still took the time to see fans when he could. “I see all the attention he gets and I try to put myself in that position,” said Sidney’s teammate Stephen Dixon. “He is such a good person. He is very accommodating to the fans in signing autographs and to [reporters]. That, along with his talent, amazes me” [338]. Even when the Canadian staff printed out emails addressed to the players from fans, of which Sidney received more than 100 pages, he regretted he couldn’t respond dutifully. “It’s hard to read them all, just because there are so many,” he said. “We don’t get the chance to write them back, so it’s kind of tough for a lot of people who might expect a reply. But we don’t have time to do so. They just give them to us to make sure we’re aware that people are supporting us. It’s nice to see people are behind you” [268].

This wasn’t The Crosby Show. Sidney was there to win, not to peacock. He played Sutter’s system. “He was able to play the team concept,” said Greg Malone, head scout for the Pittsburgh Penguins [246]. In a way, Sidney enjoyed the anonymity of a supremely talented team. “It seemed that Crosby, so used to being the centre of attention, took special pleasure from just being one of the boys” [Taking the Game…, p. 164].

“When you have that many good hockey players, it’s easy to put a team together. But at the same time, it’s harder to win because everyone has to check their egos at the door. We did that. We’re a true team and we stuck together.” - Sidney Crosby [329]

Canada steamrolled its way to the final, where Sidney would finally have another crack at the Russians. The Russian team had embarrassed the Americans thoroughly in a 7-2 win in the semifinal. Alexander Ovechkin and Evgeni Malkin had been showstoppers in the game, combining for 4 goals and 6 points. Malkin had scored a highlight-worthy goal in the third period, and the Russians were more than confident as they geared up to face the Canadian juggernaut. “Canada is a good team, but they’re not gods,” Ovechkin said blithely. “No one knows how good their goalie is” [220].

The Canadian goalie, Jeff Glass, hadn’t faced much difficulty in the tournament thanks to Canada’s tough defensive system. Against the Russians, the Canadian defense would have to be at the top of its game. Ovechkin and Malkin were powerful centers for the top two Russian lines, and Russia led the tournament with 10 power play goals [351].

Sidney alone had five power play goals himself [251]. He rebuked the idea that the gold medal game would be an epic showdown between him and Ovechkin. “I don’t think it’s going to be one guy for either team that wins it,” he said. “It hasn’t been like that the whole tournament. We both have a responsibility to help out with our team scoring wise, but for sure that’s not what it’s going to turn into. We both have big roles. It’s all coming down to who wins the hockey game and I’ll try to do my best to make sure I’m doing my part to make that happen” [202].

It wouldn’t be easy for the Canadians. Russia’s goalie, Anton Khudobin, had been “the key player in his team’s two wins over the QMJHL all-stars in November.” Both games had gone to a shootout, and Khudobin didn’t give up a goal in either. “We’re going to be tested there,” said Sidney. “We’re going to have to make sure we’re driving the net.” Leading up to the game, Coach Sutter emphasized control and mental toughness. He knew what his team was capable of [351].

On January 5 at the Grand Forks arena, over 11,000 fans packed into the seats for the gold medal game. Red Canadian jerseys filled the stands as far as the eye could see. “It’s amazing when you’re not even in your home rink and we’re basically the home team,” said Sidney. “We had more fans there than the Americans” [329].

In the opening period, it appeared as if Canada had lost its coach’s message about control. Despite a sharp Getzlaf goal in the first 51 seconds of the game, Russia had four power play chances in that period alone, including a 72-second-long 5-on-3. Canada weathered the storm, earning a second goal thanks to defenceman Danny Syvret [352].

It was then that Ovechkin saw his chance. The puck on his stick, the Russian phenom cut across the ice in an attempt to avoid Dion Phaneuf. He wasn’t ready for Sidney, who was coming at him full-tilt on the backcheck. “The safe play would have been just to lock up Ovechkin, a play that most two-way first-line forwards would have made... Though [Sidney] was giving away four inches in height and at least 25 pounds, [he] didn't hesitate to lay hip and shoulder into the big Russian forward... A dazed Ovechkin did manage to get up and skate away... [but Sidney] had managed to separate Ovechkin’s shoulder” [Taking the Game…, p. 163].

Sidney’s fearless move reinvigorated the media frenzy around him. The same scout who had said earlier that Sidney was just “okay” was beyond impressed: “I’m sure that he was banged up during the tournament. So when he went into Ovechkin like he did, [that] was pretty gutsy... Everybody knows that he’s got the talent to look after defensive responsibilities—he showed that he’s willing to do it and did it against the best 19-year-old out there” [Taking the Game…, p. 165-166].

Sidney was modest in his response. “We played against the other team’s top line every game,” he said. “Getting assigned to cover Ovechkin, we had to make sure we did our job. We played it tough against him” [329].

“Sidney is an outstanding player. Last year as a 16-year-old, he made a big contribution to this team. This year, he’s older, bigger, stronger and faster. And I think having the spotlight while playing against Ovechkin and playing with Bergeron was the perfect stage for him. He went out and proved just how good he was.” - Blair Mackasey, Team Canada head scout [329]

Though Russian Alexei Emelin made the score 2-1 in the last minute of the first period, the Russian team self-destructed in the second period. Canada tallied three straight power play goals and the game was all but over, especially after Ovechkin sat out the third period because of his injured shoulder. The final score was 6-1, and Sidney had done what he’d vowed to do: help Canada to their first gold medal in seven years [6, 352, The Rookie, p. 123]

Sidney had scored 6 goals and 3 assists during the tournament, helping Team Canada outscore their opponents 41-7 during their six games [33]. Before the medals were even awarded, media was quick to crown the team as the greatest junior team to ever grace the international stage. For the dozen returning players from 2004, their stinging defeat had made the taste of victory even more motivating. “It goes back to the character of the guys we had on that team, the leadership we had on that team,” said player Jeff Carter. “Obviously, there were some great players, but they were great people and they care about winning. They’re going to do anything they can to win” [101].

“Sidney was 17, and I had such an admiration, so much respect for Sidney with the way he handled everything there. You could tell he was going to be a superstar, and you could tell he was going to be an elite player. You could tell he was going to be captain of a team someday.”

- Brent Sutter, Team Canada head coach [3]

Sidney’s trip back to Canada was a media tour. “I’m pretty tired. I can’t even speak right now,” he rasped to reporters at Trudeau Airport in Dorval after an early-morning flight from Winnipeg. He’d started losing his voice during the gold medal game. “I was trying to talk to guys, but it was so loud in the rink,” he explained hoarsely. “After the game I totally lost it.” He was about to take a connecting flight to Mont-Joli to return to Rimouski for several QMJHL games, after which he hoped to spend a few days back in Cole Harbour with his family. “I’m sure I’ll be there to have my little Christmas with my family for a few days,” he said [268, 329].

“It’s the best thing I’ve ever done... the best experience I’ve ever had. It’s something you share with your teammates forever. Nobody can take that away from you. When you get older and look back, you’ll be able to say you played with a lot of great hockey players. It’s an amazing feeling.” - Sidney Crosby [329]

He answered questions in English and French, explaining that all he’d wanted was to improve his performance and contribute more than he had at the 2004 tournament. When a reporter asked if Sidney had done any deep reflection on the flight, Sidney replied “I didn’t think about anything. I slept. I was up all night.” The rumors about his potential trade to Moncton before the January 8 QMJHL deadline resurfaced, and Sidney brushed them aside with amusement. “I’m not really sure what’s going on there, but I’m sure I’ll be back in Rimouski,” he said. “I’m not too worried about it. That’s not something that’s on my mind a lot” [239, 268].

Another reporter asked where the silver medal from 2004 was. “I have no idea,” said Sidney, flashing a toothy grin [329].

His old silver medal was safe at his parents’ house.

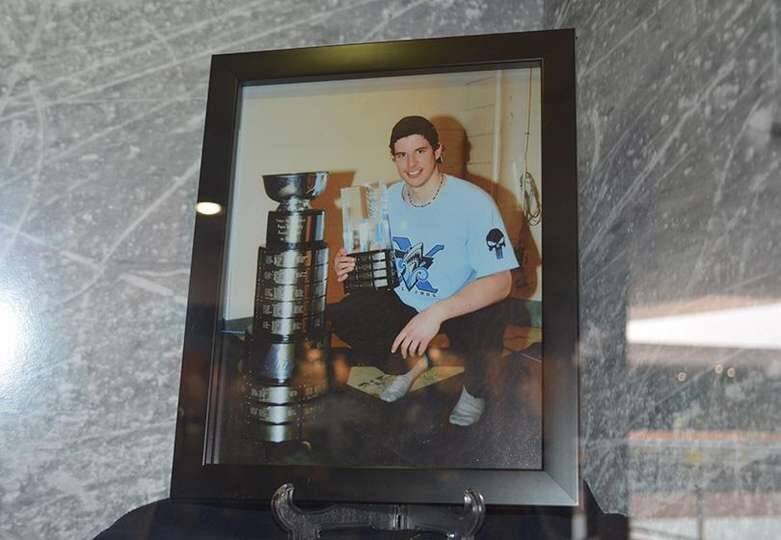

His jersey from the 2005 gold medal game, however, was not.

When Sidney arrived in Rimouski two days after Canada’s glorious win, the first thing he did was unpack his hockey bag. He had wisely kept his medal in his pocket during the flight. His skates, his pads, his gear, all of it was in his luggage... except for the red no. 9 jersey he’d worn in the gold medal game. He “knew he hadn't misplaced it. He knew he had put it in there. He wanted it to take a treasured place alongside the trophies and banners and other sweaters from other tournaments.” It was gone [119, 330, Taking the Game…, p. 167].

He called home crying.

“It’s hard to explain what he’s feeling,” Troy Crosby told The Globe and Mail. “It’s just a sick, sick feeling. No one can understand just how important that jersey is. It can’t be replaced. Winning that gold medal was so special and the jersey is the one he wore while they did it. To go from such a high feeling to such a low feeling so fast is hard” [Taking the Game…, p. 167].

Trina said that the Crosby family was not offering a reward for the jersey. “We hope whoever has the jersey realizes it’s essentially worthless to them,” she said. “It’s stolen, and as soon as it surfaces, everyone will know. Its only value is sentimental, and that is for Sidney.” Hockey Canada stepped in to offer a reward anyway. The organization had also retained all of the players’ white away jerseys for an online auction benefiting tsunami relief efforts in South Asia. They pulled Sidney’s jersey from the auction with the intention of giving it to Sidney, which forfeited the $22,000 bid it had received [119, Taking the Game…, p. 168].

Sidney was shaken. “Definitely I’m upset,” he told reporters before the Océanic faced the Baie-Comeau Drakkar. “It’s tough. You play in the best series and win, and it’s a symbol for sure. It’s something you want to keep, something you want to have. Right now, it’s pretty frustrating. I don’t know what happened to it. It could have been taken or it could have gotten lost. All I know is, it’s gone.” The sight of Sidney, red-eyed and dismayed, should have been a striking moment of clarity for the hockey world. Though he commanded the attention of a billion-dollar sport and the Canadian sports media, he was just a boy [119, 219, Taking the Game…, p. 168].

Trina, Troy, and Pat Brisson were working with Hockey Canada, who in turn was working with representatives from Air Canada, police in Grand Forks, and RCMP in Winnipeg and Montreal to recover the jersey. Four days after the jersey was reported missing, Canada Post employee Jean-Marc Saucier found a red Team Canada jersey wrapped in plastic with a newspaper clipping affixed to it in a mailbox in Lachute, Quebec, nearly 60 kilometres northwest of Montreal [119, 120].

“It was obviously his sweater,” said Saucier. “It had Crosby in big letters. And on the other side were all the logos and everything.” On the newspaper clipping attached to the jersey was a phone number for Hockey Canada, which Saucier called to report his discovery. Police in Montreal retrieved the jersey and immediately believed it to be authentic because of the “unmistakable hockey-bag odour” [120, Taking the Game…, p. 169].

“They said it smells pretty bad, so that’s a good sign.” - Sidney Crosby [Taking the Game…, p. 169]

On January 12, the Montreal police announced the arrest of a 48-year-old man from Laval, Quebec for the theft of an item worth more than $5,000. The man, an Air Canada employee, claimed he’d stolen the jersey on “impulse” to give to his 14-year-old daughter as a gift. Hockey Canada worked with the police to authenticate the jersey; once it was determined to be the genuine sweater, Pat Brisson travelled to Montreal to retrieve and personally deliver it to Nova Scotia, where Sidney was in town playing against the Mooseheads [120, 194, 218].

The Halifax stadium was sold out—only the second sell-out for the team that season, with 10,000 people crammed into the arena—and Sidney received a standing ovation before the game. The president of the Mooseheads came onto the ice to recognize Sidney as an “outstanding Nova Scotian” for his World Juniors win, and after Sidney’s second goal of the night, he got a second standing ovation to match. With his jersey on its way, Sidney was able to relax and enjoy the experience. “It was a really fun game to play tonight,” he said. “Just to be at home and to be in front of friends and family... it was really nice” [218].

Canada’s hockey-apparel-related national nightmare was finally over. Some critics thought the Crosby family had blown the situation out of proportion. “[The media story] has taken on a life of its own, a little bit,” Sidney admitted at a news conference in Halifax, holding up his found sweater in front of the gathered reporters with a broad smile. “But I’m really happy to have it back and obviously a lot to do with it has been the amount of awareness around it, there’s not much anyone can do with a jersey that’s so known like that” [194, Taking the Game…, p. 169-170].

The white jersey Hockey Canada had gifted to Sidney went back to auction. Sidney said that he accepted the apology of the thief and didn’t want to comment on the situation. “It was just a tough situation, and I just wish it didn’t happen,” he said. “It’s just nice that it’s finally here and it’s all over with. Ever since it happened, it’s been a pretty big deal and it’s been a long few days just waiting to finally get it, so it’s nice to have it” [194, 218].

Sidney’s brief Christmas-and-New-Year’s interlude in Cole Harbour had not been as restful as he’d hoped.

It was about to get worse.

The Home Hardware CHL/NHL Top Prospects Game was a showcase for major junior prospects across Canada. Forty of the CHL’s top players eligible for the 2005 NHL Draft were invited. The CHL had announced its list of invitees before World Juniors with Sidney as the marquee name, featuring him heavily in promotional materials for the game. He would be “the main attraction and the selling point for the event,” which would be nationally televised on Rogers Sportsnet. Ron Toigo, the owner of the hosting team—the Western Hockey League's Vancouver Giants—projected a sellout crowd of 16,000. “The hype over the Top Prospects Game [could not] be overstated.” 15,000 tickets had already been sold by January [210, 212, Most Valuable, p. 121].

The Western League in particular was eager to take a bite out of Sidney. The WHL had a “well-entrenched superiority complex in its junior game,” and the reporting over Sidney’s small role on Team Canada meant the WHL wanted to see how the QMJHL’s golden boy would hold up against the WHL’s best players, namely Gilbert Brule, the Vancouver Giants’ hometown hero. Though Brule hadn’t played for the National Junior Team, he was an “aggressive and intense” player and put up good numbers in the WHL: 23 goals and 31 assists in 41 games. Sidney had 29 goals and 52 assists in 37 games [212, Taking the Game…, p. 170].

“Crosby is a known because he’s in his own league at this stage of development. That separates him from Brule for the moment. Brule will play in the NHL, though, because he has the qualities you look for. He can skate and he’s got grit. He can score. This isn’t like an all-star game because these guys actually play hard. They’ve actually had fights in this game, with some really big hits.” - Ron Delorme, chief amateur scout for the Vancouver Canucks [212]

Even more exciting was the prospect of Sidney having to share space with Don Cherry, who was serving as an honorary coach for Brule’s team. Would Cherry bluster about Sidney’s attitude again? Would Sidney take it with a smile? It would be a feeding frenzy for sports media and fans alike [Taking the Game…, p. 170].

Or, at least, it would have been. Days before the event, Sidney opened the door wide to a controversy bigger than his public spats with Don Cherry, his lost jersey, or even his on-air fumble about scab labor. The hockey world exploded when officials announced that Sidney had pulled out of the Top Prospects Game [Taking the Game…, p. 169-170].

Sidney revealed that he had sustained a back injury during the gold medal game and had been playing through the injury since he returned to Rimouski. In the 5 games the Océanic had played since World Juniors, Sidney had dressed for 4 of them. “The final decision was made by Sidney himself after this afternoon’s game in Moncton,” said Doris Labonté. “Since he won the gold medal with Team Canada at the World Juniors, he hasn’t been in top shape. Emotionally, he is drained. Sidney’s health comes first. The time has come for him to rehabilitate physically and mentally” [210, Taking the Game…, p. 170].

“It’s hard. It’s not an easy choice. It’s my draft year, you know what I mean, and I’m a competitive person as well and I was looking forward to that challenge and it would have been fun for me to go there. I was looking forward to the opportunity to prove myself against those other guys as well. I don’t really see how some of those comments are coming out, but they’re going to say [I’m exaggerating]. It’s kind of tough. That’s the way it has to be.”

- Sidney Crosby [210]

Sidney had planned on making the trip out to Vancouver for the game on January 19, but his condition deteriorated until he felt it was no longer the right choice to attend. He “declined to elaborate on his injury, believing opposing players [would] try to exploit it when he [returned] to the ice.” He insisted that it was physical pain and not fatigue that kept him from participating, as some people wondered if the stress from the missing jersey had frayed his nerves. “Fatigue is something that, mentally, I’ve always overcome that,” he said. “That’s not something that made me not go at all. Definitely it’s the injury over fatigue for sure” [210].

Nonetheless, Sidney had been flying through the hockey world at a rip-roaring pace. From attending the Canadian Junior Development Camp from August 12-19 to the Océanic’s training camp on August 25 to the Q’s regular season in September to the National Junior Team Selection Camp from December 12-16 to World Juniors from December 25-January 4 to Sidney immediately reentering the Océanic’s roster, he was worn thin [Most Valuable, p. 121-122].

The weekend before the Top Prospects Game (which fell on a Wednesday), the Océanic had a game in Charlottetown on Friday evening, Halifax on Saturday evening, and Moncton on Sunday afternoon. Sidney’s back was so bad that he sat out the game on Friday. The Océanic returned to Rimouski early Monday morning, and to make the Top Prospects Game Sidney would have needed to depart Rimouski that same day—likely on “a small plane from Rimouski to Quebec or Montreal, and then another six hours to Vancouver”—to arrive in time for media responsibilities on Tuesday and the game itself on Wednesday. He would then need to fly back to Rimouski to dress for the Océanic’s game on Friday [Most Valuable, p. 121-122].

All for a hyped-up all-star game.

Ron Toigo of the Vancouver Giants went on a media rampage. He told reporters he had offered the Crosby family special accomodations—first-class plane tickets, a Vancouver Island vacation—to attend the game. When Sidney declined, Toigo ripped into him. “For the guy who wants to be the next Wayne Gretzky,” Toigo scoffed, “the history of Wayne Gretzky is that he would be here with one leg if that’s what it took because it’s good for the game” [Taking the Game…, p. 171, Most Valuable, p. 122].

It was a low blow; Sidney more than anyone tried to quell Gretzky comparisons. Toigo stooped even lower in the coming days, drawing from the Canadian political concept of Western alienation to accuse Sidney of brushing off the WHL. “I think he’d probably be there if it was in Montreal or Toronto,” said Toigo. “Sure, it’s a long flight to Vancouver, but first-class accommodations are pretty comfortable and it’s not that long of a flight” [Taking the Game…, p. 171].

Labonté was infuriated with Toigo and sent a letter to The Vancouver Sun, the newspaper that had published Toigo’s comments. “Mr. Toigo,” Labonté wrote, “everyone is sorry for the fans, but the fans and you can only blame it on something nobody has control on. You have shown no respect for L’Océanic de Rimouski. Apologize for what you have said on our organization” [210, 331].

Toigo simply responded by saying that if L’Océanic had rested Sidney instead of playing him after he returned from World Juniors, perhaps his injury would have healed. “Somewhere this has lost focus,” said Toigo. “It’s all about the game and the fans who want to see this guy. The direction from the GM is unfortunate, very small-market minded and a real disappointment to all of us here” [210, Taking the Game…, p. 171].

Toigo then proceeded to pour gasoline on the fire by turning attention onto the Crosby family. Troy Crosby’s reputation had never fully recovered from the rumors that he was behind the Océanic’s 2004 stunt to bench Sidney over reffing disagreements. “This is so out of character [for Sidney] you wonder where that advice came from,” said Toigo [Taking the Game…, p. 171].

Toigo wasn’t the only person to turn on Sidney’s family. “He’s old enough to know better,” wrote Gary Mason of The Vancouver Sun. “But the people who deserve most of the blame are those around Crosby... people like his coach, his GM, his agent, his parents. Instead, they let him down” [Taking the Game…, p. 172].

Don Cherry, in a showing of rare restraint, held off on commenting about the situation... until the Top Prospects Game came and went, and the following weekend Sidney dressed for two Océanic games [Most Valuable, p. 121-123].

On his radio show, Cherry dug in. “Crosby said he was very tired, very fatigued and that he had a bad back. The thing that really gets me is the two games just before that he had eight points in two games. It’s beyond me how a guy could have a bad back and do that,” exclaimed Cherry. “I’m giving him the benefit of the doubt. I’m not knocking him, so now, he plays the next game for Rimouski a day and a half after the game, right? I see him knock down a defenceman, get the puck, put it in the top corner. I see him get a breakaway and take the guy and put another puck in. So much for a bad back and fatigue” [211].

Sidney didn’t respond, but Pat Brisson did. He didn’t hold back, going for both Cherry and the entire CHL. “As far as Don Cherry is concerned, to me it’s almost a disgrace to have the CHL endorsing someone who is constantly looking for attention on behalf of a young 17-year-old kid,” said Brisson. “The CHL obviously endorses it because they had him as a coach, they had him at the banquet. He’s more an entertainer and a clown than someone whose opinion I would respect” [211].

“Sidney has been pushing the envelope at the World Juniors and when he came back for his own team in Rimouski, and the timing of him to take care of this injury was proper.” - Pat Brisson [211]

Sidney admitted that the things being said about him were “tough.” Though he was used to public criticism at this age, he was still young. “It’s easy to say some of that stuff,” he said. “Anyone who knows me, and I don’t think that a lot of the people who are making some of those comments know me that well, but the people who know me know I’d be there if I could. It’s not an easy decision not to go, but I’m not going to have an injury that’s going to last me a while here at that cost. I’ll take the heat and try and move on” [210, 331].

Pat Brisson and Labonté weren’t the only people to come to Sidney’s defense. Antoine Pouliot and Mario Scalzo Jr., two of Sidney’s teammates on the Océanic, argued that Sidney’s loyalty to his team was admirable. “We were happy he did that... To be his best for our team, he needed some rest and he needed injuries to heal. By not going, he was telling us that Rimouski was more important to him than all that other stuff. It wasn’t selfish. It was exactly the opposite. Sidney is always team first,” said Pouliot. “Obviously he was putting our team ahead of personal stuff by not going [to Vancouver]. It meant a lot to us,” agreed Scalzo. “Sid was 17 but he has always known what’s the right thing to do... the message that should get sent” [Taking the Game…, p. 172, Most Valuable, p. 122].

Even outside of Rimouski, some agreed that Sidney had made the right choice. In the Edmonton Journal, writer John MacKinnon said it was a joke to think Sidney was shirking his responsibilities. “Anyone who has ever met Crosby knows he simply lives to play hockey, meeting new challenges, tests himself against the best players around and continues to master his craft,” wrote MacKinnon. He argued that Sidney had played his post-World Juniors games on pure adrenaline before admitting that he was in no shape to continue at such a pace. The Q’s playoffs loomed. Moreover, MacKinnon wrote, “[these players] are young... they look mature and they have great confidence. They are children” [224].

“The media didn’t get that one right and the criticism Sidney took wasn’t fair.” - Mike Blunden, OHL player on the Erie Otters, former teammate of Sidney’s from the U17s (Canada Winter Games) and U18s [Taking the Game…, p. 173]

Sidney’s focus was on the Q’s upcoming playoffs, and the Océanic rose to meet him. In Sidney’s first two games back with Rimouski after World Juniors, he had three goals and four assists [330]. The Océanic won their game on January 7 and would not lose again until mid-playoffs in April [50]. Their powerplay went 45% in the first ten games after World Juniors, the team going 9-0-1 and outscoring opponents 61-21 [Most Valuable, p. 121].

At the center of it all was Sidney. He had been playing with his linemates for two years, garnering a familiarity with them that elevated his play unlike anything he’d ever produced. He was stronger, more comfortable, and “was going about his business with a confidence bordering on impunity” [Taking the Game…, p. 178].

The cramped schedule the Océanic had been saddled with in the first half of the season had passed, and the wear and tear of a jam-packed regular season combined with World Juniors had taken a toll on Sidney. After World Juniors, though, he was able to relax and play a more evenly-paced schedule. “In the last few weeks I’ve started to feel more comfortable and rested again,” he confessed [Taking the Game…, p. 176].

It was having an effect. Sidney “raised his play to a new level” and tore the Q to shreds. For the rest of the regular season he was held off the score sheet in only one game, and the Océanic won and won and won. It was “the best performance I’ve ever seen by a junior,” said an NHL scout. Sidney would be named the QMJHL player of the week for the last four weeks of the season [Taking the Game…, p. 175, 191].

As the pieces of the team began to click back together, Sidney was perpetually swarmed by the media. His teammates were caught up in the flood of interviews and requests, but they weren’t bothered. Some were even impressed. “[Sidney] never says ‘I hate interviews’,” said linemate Dany Roussin. “He never says one bad word about doing interviews” [255]. Mario Scalzo Jr. would laugh when he got asked about Sidney, but he said he wasn’t sick of it. “No, it’s a ritual,” he reassured reporters. “Every time. But it’s okay” [46].

In January Sidney kicked up a bit of a kerfuffle when he was photographed signing a young woman’s chest. It was not the strangest thing he’d signed—“He said he’s autographed everything from shoes to bowling balls to bikes...”—but it was salaciously reported that he’d signed her bra. “I didn’t sign there,” he said with a laugh. “The picture was taken from the back so everyone got the wrong idea. I made sure I didn’t do that. That’s not something I’d do. I did it above on her shirt” [366].

Sidney was a rockstar. When Rimouski hosted a Quebec peewee tournament, hundreds of 12-year-olds lined up to have their jerseys and sticks autographed by Sidney. Over 13,000 people would fill the stands that night to watch Sidney and the Océanic play. RDS, the French-language sports network, broadcast the game on television. Between signings, Sidney answered questions from reporters who had traveled from Montreal. “He is our star, our Mick Jagger,” said Labonté. “This is just how it is and how it’s going to be” [Most Valuable, p. 123].

Despite his rockstar status, Sidney was still Troy and Trina’s kid at home. Trina got on his case for leaving wet bath towels on his bed when he was in Cole Harbour and denied him permission to drive from Rimouski to Cole Harbour after the season ended [49]. “In our home he’s still a 17-year-old boy,” said Troy. “Maybe somewhere else he’s Sidney Crosby, the hockey player, but he’s part of the family at home. He has to share the TV with his sister, stuff like that. He’s a normal kid. When he leaves the house, it’s a bit different, but at home he’s just a normal teenager” [314]

“I don’t think there’s any way that I would’ve been able to go through what I’ve gone through the last few years of my life without [my parents]. They’ve definitely been there to make sure that I’m going in the right direction and they’ve been there for everything. They’ve meant a lot and I couldn’t imagine going through what I have without their guidance.” - Sidney Crosby [365]